Making waves

The new generation of startups using AI to save the planet

From tracking underwater creatures to optimising sugar cane crops, more and more entrepreneurs are deploying artificial intelligence to tackle environmental challenges. But, with much uncertainty around regulation and investor appetite – and serious concerns about AI’s potential negative effects – these innovators are navigating unknown waters.

In a forest in Glarus, in eastern Switzerland, a pack of wolves is howling to the moon. It starts with what sounds like a single animal, soon joined by a chorus of fellow creatures. “It’s one of my favourite sounds that we have,” says Olivier Staehli. Before long their cries fade out, and only the gentle sound of the wind blowing through the valley can be heard on the recording.

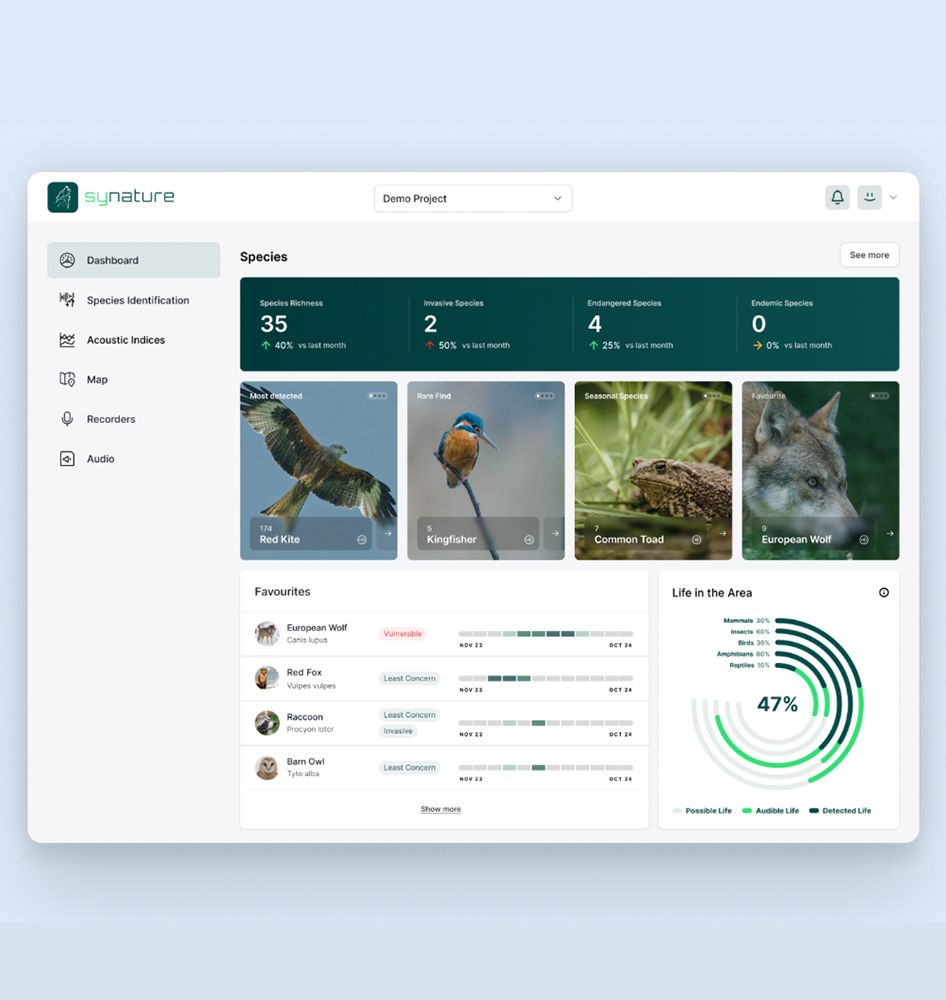

Staehli is the co-founder of Synature, a Switzerland-based startup that monitors biodiversity through sound. Using so-called “smart microphones”, positioned in key locations in nature, the startup uses bioacoustics and artificial intelligence to assess the biodiversity of a certain area.

The microphones capture sound 24 hours a day, all year round, gathering a huge amount of data. This is uploaded on a cloud storage system and interpreted through machine learning – artificial intelligence models trained on existing data to undertake complex tasks – which identifies the corresponding animal species. The result is a complete picture of all vocal creatures within the area covered by the microphone, available in real time on an online dashboard.

“We’re working on all species that make a sound somehow – some are easier and some are harder, some vocalise more often and some less,” says Staehli. “Our proposition is that we want to detect all vocalising animals, and that creates a pretty good indicator [of] where there is a healthy ecosystem or not.”

Birds are the easiest – their cries have been studied for a long time, so a large amount of data is available to train the microphones. But Synature’s technologies can identify a range of animals, including amphibians and mammals like wolves or wild boars. The presence of apex predators such as wolves, for instance, indicates an abundance of prey and thus a healthy ecosystem, particularly if those wolves are producing offspring.

An audio recording of a pack of wolves howling in Glarus Canton in Switzerland, captured by Synature’s smart microphone. (Source: Synature)

An audio recording of a pack of wolves howling in Glarus Canton in Switzerland, captured by Synature’s smart microphone. (Source: Synature)

Behind this idea is a personal love of nature. “Synature comes from my passion for wildlife, and wildlife photography,” Staehli says. “I spend a lot of days in a field, outdoors, setting up camera traps, and waiting in a camouflage tent.”

He also enjoys developing technology to solve problems, a process that began when he and co-founder Noah Schmid teamed up as students on the project that would become their business. “We like the process of unlocking black boxes and thinking: how can we solve big problems? For us, it’s really exciting,” Staehli says.

Synature still has to prove its business can work. Incorporated in 2024, it has a few dozen pre-orders for its microphone, following successful pilot trials of the product. Clients will use the microphones on a subscription model, with a fixed price per year that gives access to the hardware, data storage, AI processing and the dashboard to understand the results. Potential clients include national parks, biodiversity monitoring companies and agribusinesses.

Bioacoustics (the study of sound production, dispersion and reception in animals) was first developed in the 1950s, Staehli explains, but AI is a game-changer for biodiversity monitoring: machine learning enables the processing of large amounts of data at a very complex level that humans would struggle to match. Because of that, traditional assessments have usually involved collecting a sound sample once a year or so, Staehli says, with information biased by countless factors – from season to weather and ultimately, luck. The smart microphone is always listening, so it can monitor patterns and shifts over time – and it never misses an exceptional yet revealing event, such as an entire wolf pack howling in the forest.

Read our Impact 101: What are nature-based solutions?

Olivier Staehli, co-founder of Synature, installs a smart microphone. A passion for wildlife inspired the business idea.

Olivier Staehli, co-founder of Synature, installs a smart microphone. A passion for wildlife inspired the business idea.

Co-founders Noah Schmid (above) and Oliver Staehli first teamed up as students on the project that became Synature.

Co-founders Noah Schmid (above) and Oliver Staehli first teamed up as students on the project that became Synature.

Synature’s online platform gives users an overview of the smart microphone's findings.

Synature’s online platform gives users an overview of the smart microphone's findings.

Taking off

Synature is one of a rising number of startups exploring the use AI to make a positive impact on the planet. Startup data firm Dealroom numbers more than 400 European AI startups targeting environment-related UN Sustainable Development Goals on its database. These have raised a combined US$5.5bn, according to Dealroom’s overview of the “AI for good” startup landscape, published in March 2025.

And more and more of these startups are entering the market each year. In 2015, Dealroom recorded nine first funding rounds (the first time a startup raises funds) for AI startups focused on environmental SDGs, growing to 37 during the year 2022 (dipping to 35 the following year amid a general slowdown in the startup ecosystem).

“It has absolutely gained in profile,” says Paul Miller, CEO of the UK-based, tech-for-good venture capital firm Bethnal Green Ventures. The number of AI-focused impact startups approaching the firm for investment has gone up considerably in the past couple of years, he explains. “In the environmental sphere, certainly, it’s doubled.”

Miller suggests AI has become popular among impact entrepreneurs, who see it as a new, powerful tool to achieve their social or environmental mission. “What they’re really obsessed with is the problem they’re trying to solve,” says Miller. “As technologies become available, founders think, ‘Ok, how can I apply that to the problem that I really care about?’”

Because the technology is young and ever-evolving, founders are still uncovering what it can be used for, finding new ideas and developing new products and services, Miller says. AI for impact is growing fast, he adds. “I imagine that's going to continue growing for some time.”

A bright future

Harry Wright is the founding CEO of Bright Tide, a UK company that supports entrepreneurs focusing on climate, nature and oceans. It recently launched Sustain.AI, an accelerator programme for startups that use artificial intelligence to tackle environmental issues.

“Artificial intelligence is everywhere, it’s the future,” he says. “We’re in the midst of the new industrial revolution, where things are just changing at such a fast and accelerating pace.”

But Wright also admits there are “some moral and ethical considerations with AI”. Concerns are rising over the technology’s impact on the planet – due to its high energy consumption and water usage – and on society, with many people at risk of losing their jobs, and big tech companies training their AI models in controversial ways. Wright says Sustain.AI aims to show that AI can, however, also be used “for really good reasons, particularly around things like climate, nature and biodiversity monitoring”.

In this year’s cohort are 10 startups (including Synature) from around the world. Among them is UK-based Ecodetect, which provides underwater wildlife detection systems to marine renewable energy operators, to help them monitor their impact on marine biodiversity and mitigate any negative effects they may have.

The impact on local wildlife is not yet well known for emerging technologies including tidal stream turbines, floating offshore wind and wave energy converters, founder David Gold explains. “There are questions about collision risks with marine wildlife, such as marine mammals, whales, dolphins, seals, diving birds and fish, and what happens if they come into contact with some of these devices.”

Ecodetect gathers imaging data from multiple sources, such as video camera footage, sonar, lidar (which is similar to a sonar but uses laser rather than sound waves to locate objects), infrared cameras and others, and uses computer vision (a type of AI that enables a computer to see and interpret images like humans) and machine learning to identify different types of wildlife. This information is provided to the energy company, which can then report to regulators and, if there’s a risk, can take steps to protect local wildlife from harm – which enables the development of low-carbon energy production while protecting biodiversity.

Ecodetect technology uses machine learning to identify and track a shark from a video captured using imaging sonar. (Source: Ecodetect)

Ecodetect technology uses machine learning to identify and track a shark from a video captured using imaging sonar.

Gold launched the startup in June 2024 after a career in geoscience. It is currently piloting its technology with renewable energy companies, whose names aren’t public at this stage. The aim is to understand their needs, then develop the product, Gold explains, “rather than doing it the other way around, and building a solution and then trying to find out whether people want to buy it.”

The market is still in its infancy, Gold says, and while environmental regulation may soften over time, he is confident that public pressure will compel energy companies to measure their impact on biodiversity. “People are making much more ethical choices about where their energy comes from, and holding people to account,” he says. “So I think there will always be a market for what we're doing, and beyond the initial work that we’re doing right now.” Expansion into other industries, such as shipping and oil infrastructure decommissioning, is also a possibility for growing the business.

Paul Miller, CEO of Bethnal Green Ventures, says many more AI-focused impact startups are now approaching his firm.

Paul Miller, CEO of Bethnal Green Ventures, says many more AI-focused impact startups are now approaching his firm.

Seals are among the species present in areas monitored by Ecodetect.

Seals are among the species present in areas monitored by Ecodetect.

David Gold, founder of Ecodetect: “People are making much more ethical choices about where their energy comes from.”

David Gold, founder of Ecodetect: “People are making much more ethical choices about where their energy comes from.”

AI for impact: hype or hope?

The number of founders eager to use AI to save the planet is rising, but how big is investors’ appetite?

While investor enthusiasm for AI startups is through the roof, VCs seem to have lost interest in impact startups, in particular those working on climate issues. After years of growth, VC funding towards “climate tech” startups started falling from 2023, dropping by 30% last year, according to Dealroom figures from 2024.

Meanwhile, separate research from BloombergNEF shows an even worse picture, with climate-tech VC investment dropping by a whopping 40% in 2024.

In fundraising terms, environment and AI startups have often been pitched against each other, with investors quoted as saying that “AI has sucked the oxygen out of the room” for green startups. The picture for those that combine the two is unclear.

Read more: VC investments in impact startups worldwide fall by more than a quarter in 2024

There might be an opportunity, Bright Tide’s Wright suggests. As some investors are pulled away from the idea of making a positive impact by geopolitical headwinds, startups using AI for environmental impact can be agile about how they present themselves. Calling yourself an AI business – “riding the AI wave” – could be a way to stay relevant during this turbulent period, he says. “Unfortunately, we live in an ever-changing, I think on some aspects, less altruistic world. For those entrepreneurs, they have to repackage and redesign and re-communicate what they’re doing in a more commercial sense.”

Synature’s co-founder Staehli, however, warns that “AI is a buzzword”. Saying that one uses AI doesn’t help much anymore, “because every startup does it” – what will make the difference is the company’s business model, track record and credentials, he says.

Miller at Bethnal Green Ventures agrees. While investors might want to be associated with “very cool AI startups”, they are generally savvy enough to look at the business model beyond the tech, he says. That’s particularly the case for impact investors, given their long-term focus. VCs may be tempted to invest in AI given its sharp upwards trajectory, but impact investors looking at eight to 10-year commitments with a company will be sceptical of quick upticks in valuation.

“I do think there is a huge amount of value to be gained and huge amounts of positive impact [to be created] from artificial intelligence and machine learning and so on. But… we’re going to have to wait and see how it really plays out,” Miller says. That cautious stance is echoed in Bethnal Green Ventures’ strategy: rather than going all-in on AI, it has a diversified portfolio among different technologies, business models and impact themes.

Harry Wright, founding CEO of Bright Tide, which supports startups using AI for sustainability.

Harry Wright, founding CEO of Bright Tide, which supports startups using AI for sustainability.

Synature’s mic can spot the presence of invasive species, like ring-necked parakeets, a tropical bird now present in Europe. (Wirestock/Freepik)

Synature’s mic can spot the presence of invasive species, like ring-necked parakeets, a tropical bird now present in Europe. (Wirestock/Freepik)

SPOTLIGHT: AI and sustainable agriculture

With US$1.9m in annual turnover, Gamaya – another venture supported by Bright Tide – is an example of an established startup using AI for more efficient use of natural resources. Founded in 2016, the company provides crop optimisation and impact measurement services to sugar cane companies to make the industry more sustainable. Using machine learning to process data from multiple sources – including satellite imagery, weather and agronomic data – Gamaya can tell farmers when the best time to harvest is to obtain the highest sugar level, enabling them to increase revenue while minimising their impact on the planet.

“We like the process of unlocking black boxes and thinking: how can we solve big problems? For us, it’s really exciting.”

Plunging into the unknown

Recently, large language models such as ChatGPT have come under scrutiny because of their need for power-intensive data centres, which also require water to cool them down. But not all AI models have the same environmental impact. LLMs differ from AI models such as those used by Synature or Ecodetect, which train on specific datasets to be able to execute specific tasks, and are less energy-hungry.

AI’s negative environmental footprint is front of mind for the entrepreneurs, but they argue that this can be minimised.

Staehli’s main concern is the energy used by cloud storage, where Synature needs to keep large amounts of data collected by its smart microphones to keep training their models. He believes the positive impact of Synature on biodiversity will outweigh the negatives of energy usage, but says the company will consider buying carbon credits to offset its impact as it grows.

Ecodetect uses green data storage providers and destroys useless data before uploading it to the cloud as much as possible. Gold says the renewable energy produced by the infrastructure operating with its support will far outweigh the energy needed to power its models.

Listen to our Good Leaders podcast with Julia Stamm and Olivia Gambelin, the women driving AI for good

Beyond AI’s negative impacts, operating in such a young field comes with unknowns, starting with ever-evolving regulation. Louise Crawford, partner at global law firm Hogan Lovells, says it’s vital for tech startups to be adaptable and responsive to change: “this is often the key difference between a business with a short lifespan and one that grows and thrives.” Laws currently being developed, such as the EU’s AI Act, are likely to have a significant impact, with AI-specific regulations expected to emerge in other jurisdictions, she adds.

In a highly competitive landscape, entrepreneurs should ensure they protect their intellectual property, advises Crawford. And constantly staying at the forefront of innovation is far from easy. “You don’t have a manual, you don’t have a blueprint,” says Staehli. Ecodetect’s Gold explains how hard it is for a small startup to grow as a business while dedicating enough time to technology development. “I’m just keen not to lose our competitive advantage,” he says.

Responsibility

Experienced investors point out that, while AI is new territory, the questions it raises are familiar. Bethnal Green Ventures has been investing in impact startups for 12 years, and Miller says he has seen several waves of emerging technologies similarly leading to new startup ideas and approaches.

“What we have to be careful of is that they really understand that technology, [and that] they [have] thought through the unintended consequences,” he says.

More broadly, one must not lose the nuances in conversations around AI for good, Miller says. AI entails risks, but we need to be wary of overstating the dangers too, he points out. “There’s a chance that the whole thing gets sidelined by a huge wave of fear about it, or a huge wave of hype.

“There’s a responsibility on us, as investors, and on the founders who are trying to create impact and value from this, to try and steer that conversation so as we don’t get caught in the extremes of it, and try to have sensible conversations about what’s possible and what’s desirable.”

Synature’s smart microphones can capture sound 24 hours a day, all year round.

Synature’s smart microphones can capture sound 24 hours a day, all year round.

Louise Crawford of global law firm Hogan Lovells says startups need be adaptable and responsive as AI regulations evolve.

Louise Crawford of global law firm Hogan Lovells says startups need be adaptable and responsive as AI regulations evolve.

At the Paris AI Action Summit in February 2025, leaders of 61 countries signed a pledge to use AI ethically. (© UNESCO/Christelle ALIX, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Image cropped)

At the Paris AI Action Summit in February 2025, leaders of 61 countries signed a pledge to use AI ethically. (© UNESCO/Christelle ALIX, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. Image cropped)

Top video: Ecodetect's machine learning algorithm identifies animals and automatically creates a bounding box around the object in the frame – here a pair of seals. Above: a European shag plunges underwater near a tidal stream turbine in Shetland, UK, identified by Ecodetect's technology. (Source: Ecodetect)

Photos supplied by Synature, Ecodetect, Bright Tide, Bethnal Green Ventures and Hogan Lovells, unless otherwise specified. Chapter heading images by Freepik.

Words by Laura Joffre. Design by Fanny Blanquier.

This immersive feature was produced by Pioneers Post in partnership with Hogan Lovells and HL BaSE, the firm’s impact economy practice. The story is free to read thanks to the support of Hogan Lovells.

Get in touch if you'd like to tell your story.

J O I N T H E I M P A C T P I O N E E R S

SUPPORT OUR IMPACT JOURNALISM

As a social enterprise, we work hard to ensure our stories are as widely accessible as possible – that’s why all our stories are free to read for one week after publication.

After that, you’ll need to be a member to view them. Membership of Pioneers Post means unlimited access to thousands of interviews, news stories, features, expert insight and explainers, all focused on helping you to do good business, better.

It also means you’re helping to sustain our journalism. As a Pioneers Post reader, we know you value thoughtful and thorough reporting on the impact economy – but you also know that producing quality work doesn't come free. We rely on our members to sustain our journalism – so please consider investing in our mission.