Against the odds

The growing green businesses of the Middle East

Running a healthy business that helps both people and planet is already a big ask. Add sky-high inflation, unbearable heat, instability and even outright war, and the task would feel impossible to most. But, for the pioneers of green business in Palestine, Lebanon and Egypt, sticking to the mission just makes good business sense. Championed by some steadfast supporters, they’re surviving and growing through the most volatile of times.

Palestine has long suffered serious water shortages. So a Palestinian startup, Flowless, has created technology that helps water utility companies and farmers to pinpoint leaks and reduce waste. It now has customers as far afield as Ireland and Kenya.

In Lebanon, where poverty has tripled in the past decade, FabricAid collects donated clothing and sells it at low prices. With 14 stores in its home country and in Jordan, the social enterprise has pioneered the region’s second-hand clothing market.

And in Egypt, Delta Oil collects used cooking oil to be turned into biofuel for export, reducing waste and preventing carbon emissions while providing paid work to hundreds of women.

> FabricAid

> Flowless

> Delta Oil

They’re just three examples of Middle East ventures responding to problems in their own communities – neatly combining green innovation with creating jobs or boosting livelihoods. That dual focus makes a lot of sense. Carbon emissions are rising sharply in the region. The impacts of climate change are staggering: the Middle East is warming twice as fast as the global average, and combined with North Africa is the world's most water-stressed region. And, while not poor overall, it is the only part of the world where poverty has been consistently rising since 2014. “We’re going in exactly the wrong direction,” says Myrna Atalla.

Atalla is the outgoing executive director of Alfanar Venture Philanthropy, which provides funding and management support to social enterprises in Palestine, Lebanon, Egypt and Jordan – including Flowless, Delta Oil and FabricAid. Created 20 years ago, it now has an explicit focus on environmental sustainability, alongside education, empowerment and employment.

Other champions of entrepreneurship also combine these objectives. Spark, a Dutch nonprofit that helps young people in crisis and conflict zones, runs Green Forward, which aims to strengthen business support organisations in seven countries in the Middle East and North Africa, aiming to nurture a green and circular economy. And the UN-backed SEED: Promoting Entrepreneurship for Sustainable Development programme has supported what it calls “eco-inclusive” enterprises in 40 countries over the past two decades, and since 2022 operates in Morocco. David Waibel at Adelphi, a German consulting firm that is implementing the SEED programme, says the programme works with enterprises that are “directly responding to the problems they see day to day”.

Yet social enterprise is not widely understood in much of the region. Backing green innovation is often seen as too risky, and many investors from outside the region are wary about getting involved there. That, say both social entrepreneurs and their longtime supporters, needs to change.

From ‘grantpreneurs’ to self-sufficiency

Small and medium-sized businesses are widely considered a powerhouse for economic growth and employment. They play a particularly important role in low and middle-income countries. In Morocco, youth unemployment is high and female participation in the labour force is low, says Waibel; any business that trains or employs these groups can quickly make a big impact.

There is plenty of support for commercial startups in the region, Atalla says, particularly for early-stage ones. What’s often missing is help for growing social enterprises, which is where Alfanar – described as “the first venture philanthropy organisation in the Arab world” – sees its role. (Alfanar prefers the term ‘Arab world’, or ‘Arab region’, referring to the 22 countries in the Arab League; some others refer to the more loosely defined Middle East and North Africa region.)

Its flagship Sustain programme typically involves three to five years of patient, flexible grants or zero-interest loans of around £250,000, plus management support and help with impact measurement. Where in-house expertise is lacking, Alfanar brings in outsiders: law firm Hogan Lovells, for instance, provides pro bono legal support to social enterprises. A newer Seed programme supports earlier-stage social enterprises for up to eight months, aiming to get some of them onto the Sustain pathway. The Seed stage also allows Alfanar to gauge entrepreneurs’ openness to hands-on input, which is a key feature of the venture philanthropy approach. That doesn’t mean you have to follow every piece of advice, Atalla explains, “but if you’re just looking for a cheque, you should definitely go elsewhere”.

Read more about the venture philanthropy approach in our interview with Isabelle Irani of Sumerian Partners

Backing startups is appealing to many funders. It’s so popular, in fact, that some insiders talk of “grantpreneurs” – founders who rely on jumping from one grant to the next. “A lot of green SMEs kind of suffer from this grant dependency,” says Moritz Blanke, a manager at Adelphi.

Prior to Alfanar, Atalla worked in international development in Lebanon and the region, where she found it “really disheartening” to see organisations adapt their focus as donor priorities shifted. She became obsessive, she says, about finding ways to invest in organisations that are accountable, not to donors, but to their customers or employees.

Grant dependency is particularly pertinent in places like Palestine, which has attracted billions of dollars in aid over the years. Many see that as deeply problematic. For instance, BuildPalestine, a homegrown initiative focused on social innovation, calls “for an alternative to traditional aid, one that directly empowers Palestinians to respond to the needs of their community in a more agile and resourceful way”.

Yet social enterprises – because they operate in complex markets, or are developing new concepts – often need a boost before becoming self-sufficient. BuildPalestine offers bootcamps, fellowships and help with crowdfunding. Alfanar tries to balance the need for long-term, flexible funding with a more businesslike approach, by providing a mix of grants and zero-interest loans. In the current financial climate, zero-interest effectively means subsidised loans, offering a gentle introduction to repayable finance. Alfanar says the social enterprises it supports benefit on average 37% more lives and generate 34% more revenue by selling goods or services as a result.

“War starts, and you need to think again”

Atalla is no stranger to challenging situations: she took on the top job at Alfanar in 2010 following the untimely death of the founder, and just months before the Arab Spring – a wave of pro-democracy protests and uprisings across the region – kicked off. Despite this, she has expanded Alfanar’s reach from one country to four; since she joined, it has helped more than 185 impact enterprises and provided over £6m in funding, and another £6m worth of management support. In 2022 it made its first equity investment, in Lebanese second-hand clothing business, FabricAid, having supported the business since 2018. “We knew there was a bright spark there,” Atalla recalls.

Alfanar itself relies on donations, and this has become one of its biggest challenges. Events of the past few years – earthquakes in Turkey and Morocco, floods in Libya, war in Sudan, Gaza and Lebanon, and rising numbers of refugees in many countries – have added to the strain on donors in the region. “I won’t lie – fundraising is very difficult,” says Atalla.

Even more difficult is working with enterprises in a war zone. Until 2023 Spark had been running several programmes in Palestine to help strengthen the wider environment for startups, including in Gaza. “We built a great ecosystem there,” says communications manager Ibrahim Banat, but then, “out of nowhere, war starts, and you need to think again”. Since the Hamas attack on Israel on 7 October 2023 and the subsequent, devastating retaliation in Gaza, much of Spark’s work in Gaza has been suspended, although it continues in other parts of Palestine.

Read more stories of social enterprise amid conflict: Can social entrepreneurs help pave the way to peace in Yemen?

Alfanar currently supports just a handful of social enterprises in Palestine; among them is Flowless, which is based in Ramallah. Atalla recalls the farmer who described leaving his home every morning at around 5am, and spending four hours at Israeli checkpoint on the way to tending crops in his greenhouse. Further delays at the checkpoint would mean his crops could die under the intense heat, but using Flowless’s technology meant he could schedule irrigation remotely. “Here’s innovation enabling livelihoods in the face of massive obstacles,” Atalla says.

In September 2023, Alfanar approved investment in Flowless. Then came 7 October. “At a moment of unbelievable tragedy and loss, it can be hard to know what to do as a venture philanthropy organisation, which is not humanitarian in focus,” says Atalla, adding, “sometimes the most disruptive thing we can do is stick to our mission and keep doing it.” Flowless received its first chunk of money from Alfanar at the end of October 2023.

Investors hesitant

Entrepreneurs are less fazed than one might expect by the immensity of conflict and instability. Lebanon has endured a litany of upheavals: the massive explosion in Beirut in 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic, currency collapse, and now war. But FabricAid founder Omar Itani – speaking to Pioneers Post in early September – shrugs these off as issues facing every business there: for him, the real challenge is tied with the social enterprise model. For Flowless co-founder Baker Bozeyeh, the issue isn’t so much what’s currently going on in Palestine as the excessive caution of investors to get involved.

For green businesses, the challenge is magnified. Although it varies from country to country, a lack of awareness among governments of what’s at stake for the planet, and of the potential solutions, is one of the big barriers, says Afef Ajengui, a programme manager at Spark. Investors still haven’t grasped the potential returns they could gain from green ventures, or are concerned about what they see as risks associated with untested technologies or business models, according to a 2023 report by Spark.

Support organisations are trying to change all this. VC investors are fairly common, but social entrepreneurs rarely get to meet them – one reason why Alfanar has been supporting the launch of a regional impact fund. BuildPalestine had planned to launch its own impact fund in October 2023; it has paused this for now, but continues its support in other ways. Hogan Lovells has advised both Alfanar and some of its investees; Rahail Ali, managing partner at Hogan Lovells' Dubai office, says social enterprise is “such a powerful tool for impact, often in the most difficult of circumstances... we see investing in the sector as an important use of our legal skills”.

Successful startups sometimes move abroad where regulations are more favourable, says Banat, so Spark works on encouraging appropriate government policies. And Adelphi’s SEED programme works with banks and other financial institutions to ensure the availability of finance for green business, particularly in Morocco’s smaller cities, where opportunities are more limited. Both Spark and Adelphi emphasise the importance of nurturing local partners – creating a whole network of business support organisations that will continue long after any project funding has run out.

Atalla believes there’s plenty of room for more impact investors from outside the region. “You don't have to ‘go big, or go home’. The best way to learn what's in the market is to put out some funding and see what comes back.” And she reckons the potential is huge. “There are so many ambitious, promising, investable social enterprises. These changemakers give us mounds of hope and inspiration.”

Many of the world's most water-stressed countries are in the Middle East. Flowless, a tech startup, aims to reduce water waste (Freepik).

Many of the world's most water-stressed countries are in the Middle East. Flowless, a tech startup, aims to reduce water waste.

Social enterprise FabricAid, in Lebanon, has pioneered the region's second-hand clothing market.

Social enterprise FabricAid, in Lebanon, has pioneered the region's second-hand clothing market.

Delta Oil works with local partners, who collect and weigh used cooking oil from households in Egypt.

Delta Oil works with local partners, who collect and weigh used cooking oil from households in Egypt.

Myrna Atalla was until recently the executive director of Alfanar, the first venture philanthropy organisation in the Arab region.

Myrna Atalla was until recently the executive director of Alfanar, the first venture philanthropy organisation in the Arab region.

Spark, a Dutch NGO, has supported startups including Blue Filter, which aims to increase access to clean water for families and farmers in Gaza.

Spark, a Dutch NGO, has supported startups including Blue Filter, which aims to increase access to clean water for families and farmers in Gaza.

The UN-backed SEED programme supports eco-inclusive businesses in Morocco – like Alguno, which produces organic fertilisers from marine algae.

The UN-backed SEED programme supports eco-inclusive businesses in Morocco – like Alguno, which produces organic fertilisers from marine algae.

Alfanar focuses on employment, education and empowerment as well as environmental outcomes.

Alfanar focuses on employment, education and empowerment as well as environmental outcomes.

A mother waits for her son to be pulled from the rubble after the 2023 earthquake in Kahramanmaraş, Turkey (Emre Sercan Ike / iStock).

Wietse van der Werf, a former marine engineer, says there is a huge need for young talent in marine industries.

Flowless helps farmers in Palestine to reduce water waste, and aims to make its technology as affordable as possible.

Flowless helps farmers in Palestine to reduce water waste, and aims to make its technology as affordable as possible.

“At a moment of unbelievable tragedy and loss, it can be hard to know what to do... sometimes the most disruptive thing we can do is stick to our mission and keep doing it.”

FabricAid: Lebanon's second-hand trailblazer

Omar Itani was shocked when he realised the used clothes he was donating to the concierge in his apartment block in Beirut were going to waste – simply because they didn’t fit. With a simple Facebook post, he started an initiative to collect donated clothes, and match them with what people needed. When the volumes he was collecting got out of hand – and his mother threatened to kick him, and the clothes, out of the house – Itani sought to pass them on to a charity.

But he discovered that charities in Lebanon didn’t have an efficient way to distribute donated clothing either, nor were there any specialised organisations doing so. So he decided to start one, and by 2018 his volunteer-led initiative became a social enterprise: FabricAid, which collects donated clothes in dedicated bins around the city and sells them in its own shops at a very low price.

“There are around 77m people in the MENA region who can’t afford decent clothing,” Itani says. “We don’t think we can kill poverty, or destroy poverty, but we think there’s a symptom of poverty which we can completely eradicate.”

FabricAid now has 14 retail stores in Lebanon and Jordan, and plans to open some in Egypt soon. It employs 50 people, and in 2023, collected 132 tonnes of clothing.

Like other businesses in the region, Itani has faced reluctance from potential investors. “There’s continuous social and security issues, which have a big impact on fundraising. In Lebanon in particular, we passed through a lot: the Beirut blast, a revolution, Covid and the currency collapse, and now a war.”

But these issues are common to any business operating in Lebanon. In fact, one of the biggest challenges for FabricAid, Itani explains, is to find the right balance between supply, demand and pricing. Demand is high – poverty rates tripled over the past decade in Lebanon – but the business doesn’t receive enough donations to match this demand. In a classic business model, this would simply drive prices up. But the whole point of FabricAid is to remain affordable for people in poverty, meaning its shops risk having some empty shelves.

To fill these gaps, FabricAid partners with brands such as H&M and Levi’s, to collect lightly damaged items that they would otherwise discard. The social enterprise also increased the number of collection bins and has upped its marketing to encourage donations.

FabricAid has had funding from Spark, the Islamic Development Bank and the Islamic Solidarity Fund for Development. But fundraising has been a complicated journey. “In the region, there is no infrastructure to fund social enterprises… we suffered from it because we were one of the first social enterprises to really scale in the area,” says Itani.

For that reason, Alfanar’s support was crucial, Itani says. Beyond initial funding, many of FabricAid’s current investors and partners were secured through Alfanar, and counselling and advice from their team was precious. “Their footprint is on every element,” he says. He considers two Alfanar team members, Fadel Zayan and Michelle Mouracade, as almost his co-founders.

In 2021, FabricAid raised a US$1.6m seed funding round from Alfanar and Dubai-based VC firm Wamda, the largest seed round raised by a social enterprise in the Arab region to date, according to Alfanar. “I think we are laying the groundwork to make it hopefully easier for other social enterprises,” says Itani.

FabricAid has 14 stores in Lebanon and Jordan and plans to open soon in Egypt.

FabricAid has 14 stores in Lebanon and Jordan and plans to open soon in Egypt.

Omar Itani realised that charities in Lebanon didn't have an efficient way to distribute second-hand clothing – so he created a venture to do just that.

Omar Itani realised that charities in Lebanon didn't have an efficient way to distribute second-hand clothing – so he created a venture to do just that.

FabricAid also upcycles some of the donated clothing into contemporary fashion items as part of its own Salad brand.

FabricAid also upcycles some of the donated clothing into contemporary fashion items as part of its own Salad brand.

Around 50 people are employed by FabricAid.

Around 50 people are employed by FabricAid.

Flowless: Palestinian water waste warriors

Five years ago, Baker Bozeyeh, who was working for a Palestinian water utility company, grew frustrated at how much water was wasted every day – simply because data wasn’t monitored efficiently. “I started to look for a solution. What's out there? How are people tackling those problems?” he recalls. The idea of Flowless emerged: a company that would use technology to optimise the use of water – and eventually, tackle the global water crisis.

Together with co-founders Osama Hnini and Eyad Arafat, both engineers, he started “playing with gadgets, small equipment and microprocessors”, to create a working prototype. They started with a small project in the Palestinian Jordan valley, and soon expanded, first locally, then around the Middle East and internationally.

The social enterprise targets two major water-consuming sectors: water utilities (the companies that bring drinking water to individuals), and farming. It instals sensors across the water network to measure indicators such as water pressure in pipes or soil moisture. The sensors send the information to a central data processor that analyses it in real time, looking for any anomalies to help detect faults as soon as they emerge. The data also helps to improve water management – for example, by enabling farmers to use automated, precise irrigation practices.

In 2022, this technology led to 300,000 cubic metres of water saved through detecting leaks and reducing water loss, benefiting 23,000 people, according to the company. Meanwhile, farmers saved an average of 21% on water and energy costs thanks to Flowless’s smart water management systems.

At the heart of Flowless’s success, Bozeyeh says, is its simplicity of use. “Our customers just don't have time to go through charts and tables and fancy analytics... I’m a data nerd, but it’s not for everyone,” he adds with a laugh.

In the Palestinian Jordan valley, most farmers have smartphones. Flowless has introduced an artificial intelligence chatbot that “translates” complicated analytics into everyday language. Farmers can ask for information; or they can use their smartphone to turn on a pump from a distance, or schedule irrigation for when they can’t get to their farm.

But good tech that provides valuable insights costs money. Bozeyeh acknowledges this, but, he adds, “this does not mean that we cannot make it affordable”. For farmers, Flowless has created “clusters” to split the costs between several farmers. For utility companies, a “software as a service” approach means clients avoid the large upfront fees of purchasing hardware. In some cases Flowless uses a benefit-sharing model that allows customers to pay a share of savings made through improved water management.

Flowless is quickly expanding overseas and now counts 12 permanent team members. But its solid business model doesn’t mean it has been easy to fundraise to support its growth.

“There are all these stereotypes around Palestine,” Bozeyeh explains, despite the fact that some areas boast a vibrant startup scene. “People think that we are in tents, under missiles, 24 hours a day, so [investors] don’t have trust… This has made fundraising a real struggle, not only for Flowless, but also for all startups in Palestine.”

This led Flowless to stop fundraising a couple of years ago, to focus on product development, while exploring other potential funders such as impact investors. In the meantime, the startup is still bootstrapping.

This is why support from Alfanar – which includes funding and technical assistance – was so valuable, Bozeyeh explains. “They opened a lot of doors to us. They connected us with potential partners, with service providers, with mentors and advisors. This is really sometimes even more beneficial than the money.”

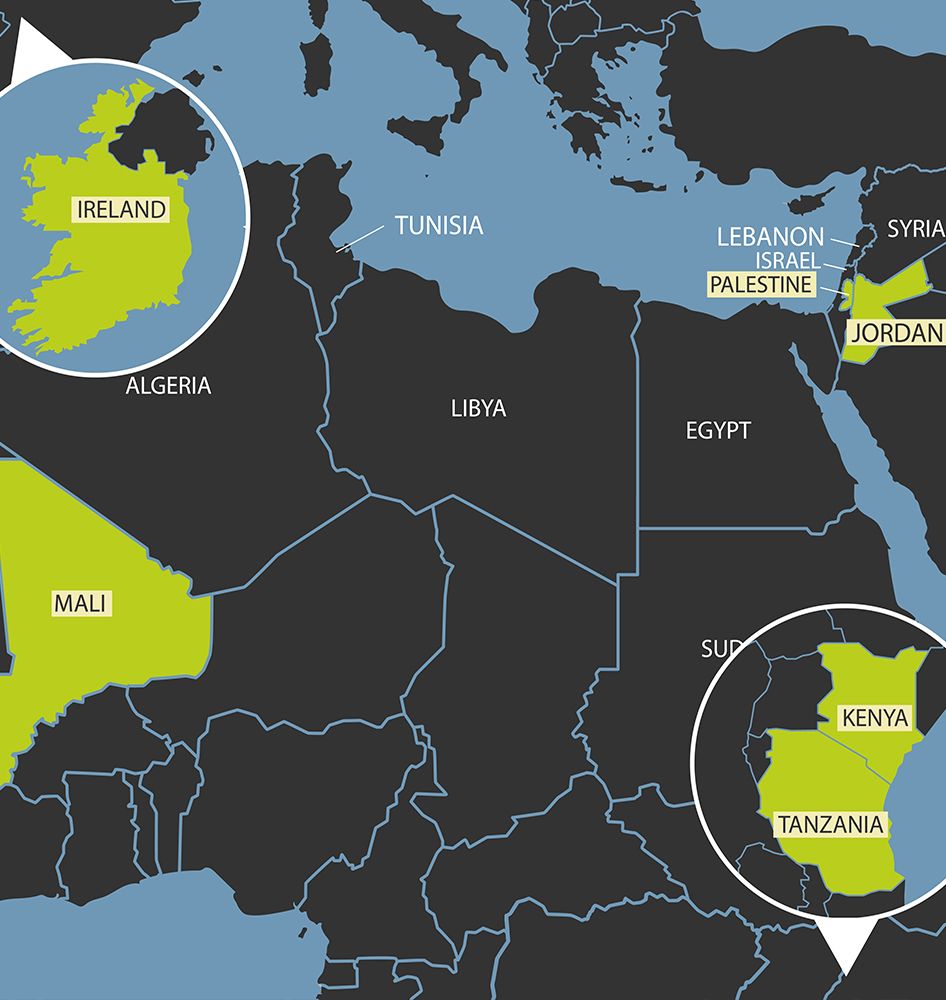

Flowless operates in Palestine, Jordan, Mali, Tanzania, Kenya, and Ireland.

Flowless operates in Palestine, Jordan, Mali, Tanzania, Kenya, and Ireland.

Baker Bozeyeh previously worked for a water utility company, where he saw that water was being wasted unnecessarily.

Baker Bozeyeh previously worked for a water utility company, where he saw that water was being wasted unnecessarily.

With Flowless, farmers can use their smartphone to turn on a pump from a distance, or schedule irrigation for when they can’t get to their farm.

Another business supported by Bright Tide is SafetyNet Technologies, a precision fishing startup.

Making the technology simple to use is key to Flowless's success, according to the company.

Making the technology simple to use is key to Flowless's success, according to the company.

Delta Oil:

Barrels of impact in Egypt

Millions of households in Egypt throw several litres of used cooking oil down the drain each month – not only polluting fresh water, but also discarding a valuable resource.

With minimal transformation, used cooking oil can be used as a biofuel – a net-zero source of energy, which has a huge market in Europe. In 2018, young entrepreneurs Serag Moussa, an industrial engineer, and Mahmoud Eljendy, a chemical engineer, spotted a promising business opportunity – and a chance to “do the right thing” by taking on this challenge. So they launched a social enterprise to do just that: Delta Oil.

“No one understood the value of that used cooking oil,” says Moussa, now CEO of Delta Oil.

But there was a catch: how to make it viable to collect tiny amounts of oil from millions of homes, scattered across a country in which more than half the population lives in rural areas?

So Moussa and Eljendy thought of building a network of local partners in villages and neighbourhoods. These partners, typically women who are well connected with the local community, collect used cooking oil from nearby households. Each household that brings some used oil receives payment in the form of something like rice, eggs or detergent. Once the local partner has collected a substantial amount of oil, Delta Oil collects it and the partner receives a commission.

Incentives like these can achieve so much more for the environment than efforts relying solely on raising awareness, says Myrna Atalla of Alfanar, which has supported Delta Oil’s growth. And, in an economy where inflation hit 40% in 2023, “getting a bag of sugar for your used cooking oil is a really good deal,” she says.

Delta Oil processes the cooked oil, to be sold to European biodiesel markets. The business has a triple impact: reducing waste, lowering carbon emissions and providing an additional source of income to women across the country. “The bigger social impact we have, the bigger environmental impact we get. It’s in Delta Oil’s DNA,” says Moussa.

It took some time and patience to turn theory into reality. “I didn’t believe it would work until we exported our first barrel in 2021,” says Moussa. With funding from accelerators and startup grants, the team learned step by step how to overcome the challenges they faced. Collecting the oil was just one of them; they also struggled during the Covid-19 pandemic to get the certification needed to export biofuel to Europe, due to travel restrictions, and had to get to grips with the complex logistics of shipping.

“We knew nothing about exporting,” remembers Moussa, with a smile. “But the good thing with the team is that we are curious, we want to learn new things.” They took courses, asked other businesses for advice – and learned. “If you are young, and you want to build something, people will help you,” he says.

To date, the social enterprise has collected nearly 10,000 tonnes of used cooking oil, abating 3,000 tonnes of carbon emissions, and made US$11.8m of revenue. It has been backed by angel investors and VC firm Den VC.

The concept of social enterprise is not well understood in Egypt, says Moussa: most of his buyers are interested in doing business, with social and environmental impact considered the realm of charities or NGOs. Currently, Alfanar is helping Delta Oil to better measure its impact, in order to access new opportunities – whether that’s new markets or investment. “We knew that we had an impact, environmental and social, but we didn’t care about measuring and documenting it.”

Delta Oil operates in Egypt, where more than half the population lives in rural areas.

Delta Oil operates in Egypt, where more than half the population lives in rural areas.

Delta Oil staff test and inspect used cooking oil before it is filtered and prepared for export.

Delta Oil staff test and inspect used cooking oil before it is filtered and prepared for export.

The company also ran an awareness campaign to highlight the value of used cooking oil – and the environmental harm it causes when disposed in sewage systems.

The company also ran an awareness campaign to highlight the value of used cooking oil – and the environmental harm it causes when disposed in sewage systems.

A Delta Oil team member inspects a sample of oil.

A Delta Oil team member inspects a sample of oil.

Images supplied by Alfanar, FabricAid, Delta Oil, Flowless unless otherwise stated. Top picture: a Delta Oil team member at the company's exporting hub.

Words by Anna Patton and Laura Joffre; design by Fanny Blanquier.

This immersive feature was produced by Pioneers Post in partnership with Hogan Lovells and HL BaSE, the firm’s impact economy practice.

Get in touch if you'd like to tell your story.

J O I N T H E I M P A C T P I O N E E R S

SUPPORT OUR IMPACT JOURNALISM

As a social enterprise ourselves, we’re committed to supporting you with independent, honest and insightful journalism – through good times and bad.

But quality journalism doesn’t come for free – so we need your support!

By becoming a fully paid-up Pioneers Post subscriber, you will help our mission to connect and sustain a growing global network of impact pioneers, on a mission to change the world for good. You will also gain access to our ‘Pioneers Post Impact Library’ – with hundreds of stories, videos and podcasts sharing insights from leading investors, entrepreneurs, philanthropists, innovators and policymakers in the impact space.