From billions to trillions: finding the funding to address the world’s biggest challenges

The Asia-Pacific region has been hit hard by the climate crisis, the Covid-19 pandemic and economic turbulence. Yet there is growing wealth in the region which could tackle head-on the world’s deepest problems. As the G20 summit comes to Asia in 2022 and 2023, innovative investors – from philanthropists to private sector players – are developing new approaches to encourage others to invest to push forward positive social and environmental change.

The annual G20 summit – this year to be held in Bali in November – is just two concentrated days of discussions between heads of state, ministers and other government representatives, but it’s the culmination of months, even years, of work behind the scenes to influence proceedings. Now, with six months to go, different groups with different priorities are jostling for position, pushing their causes through the G20’s various working groups and taskforces, with the hope of recognition in the G20’s final communique.

This year, after two years of pandemic, the ever-worsening climate crisis and instability on the world’s markets, the theme of the forum for international economic co-operation is ‘Recover together, recover stronger’. And with Indonesia hosting the event this year, followed by India next year, many people in Asia-Pacific feel that this is the right time to push the discussion centre stage about how the world’s resources can be used more effectively to address the potentially devastating global challenges we face.

Global leaders have already signed up to a plan to address the world’s problems – including poverty, climate change and health inequalities – the Sustainable Development Goals, which were adopted by all United Nations member states in 2015 and have a target to be reached by 2030. Yet, achieving them seems to be moving ever further out of reach, particularly in developing countries: the latest estimates from OECD show a massive annual finance gap of $4.2tn.

Professor Bambang Brodjonegoro, a former senior minister in the Indonesian government, now an academic and co-chair of the G20’s think tank, the T20, says: “Everybody has to realise that due to the two years of pandemic, the financing needed to achieve the SDGs by 2030 will be much more difficult to get. So a breakthrough is very much needed.”

In his opinion, the G20 is a key opportunity to grasp: “The G20 should take the role as leader to at least create the framework of how to get the financing needed for the SDGs.”

Professor Bambang Brodjonegoro: "A breakthrough is very much needed"

Professor Bambang Brodjonegoro: "A breakthrough is very much needed"

The G20 comes to Indonesia

The 17th G20 Heads of State and Government Summit takes place in Bali from 15 to 16 November 2022

It brings together 19 countries plus the European Union with Spain as a permanent guest

The members represent 60% of the world’s population, 80% of global GDP and 75% of global exports

This year’s three pillars are:

To restructure the global health architecture

To push forward the digital economy

To accelerate the transition to cleaner energy

Professor Bambang and many other Asian leaders, brought together through the new Asian Impact Leaders Network, created by social investor network AVPN and the Rockefeller Foundation, are keen to stress that the funding already exists to tackle health inequalities, create jobs for young people and find solutions to the climate crisis. Tristan Ace, chief product officer at AVPN, points out that, in spite of the pandemic, private wealth has continued to grow – worldwide, high net worth individuals held more than US$80tn in 2020. He adds: “Many wealth holders recognise their role in addressing social and economic disparities on the ground.”

But a catalyst is needed to accelerate and direct some of these trillions of dollars to where they can make a positive difference.

The concept of sustainable finance has gained ground on the world stage in recent years. In 2019, AVPN, with the Rockefeller Foundation and consultancy FSG highlighted in a report, Financing the Future of Asia, “a wave of innovation sweeping across the financial sector” in which investors were using an “ever growing range of instruments to achieve social and environmental benefits, while producing attractive returns”.

“This,” the authors said, “is the exciting field of sustainable finance, and it is growing fast.”

Sustainable finance is a broad field encompassing investments based on environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors, green bonds which are issued to fund environmental improvements, and microloans to the poorest people as pioneered in the 1980s in Bangladesh. Impact investing – investing in businesses that focus on social or environmental goals – has become popular in many parts of the world, with the UK launching the world’s first impact investment wholesaler Big Society Capital, ten years ago.

- Read more: Impact investments worldwide reach $1tn

Some of these approaches, particularly investments with an environmental focus, have really taken off. Global sustainable and responsible investments (including ESG investments and impact investments) reached US$35.3tn in 2020, a growth of 15% in two years, according to the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance. But Professor Bambang has a warning. “Of course there will be a lot of green financing needed in order to achieve environmental sustainability,” he says. “But don’t forget we still have the social sustainability side too. We need to increase the role of financing for social sustainability.”

He hopes that during Indonesia’s presidency of the G20, followed by India’s presidency next year, more emphasis can be given to the other types of finance that lower and middle income countries really need. He knows that these countries can’t rely solely on public finances. Private investors, he adds, are keen to pursue strong financial returns. “Most will go for environmental sustainability because the business case is quite clear,” he says. “In social sustainability, it is more difficult for private financing to find a business model. So blending private finance with social finance – philanthropy – will be critical.”

And so ‘blended finance’ is the concept that Asian leaders are keen to highlight during the G20. Tristan Ace says: “Blended finance is a huge opportunity for developing countries that isn’t yet being tapped into. It’s about aligning resources in the most effective way to unlock capital.”

“It’s time for blended finance to reach its full potential and meet its promise of attracting private capital into emerging markets at volumes never seen before,” says Joan M Larrea, the CEO of Convergence, the global network for blended finance, pointing to the urgent challenge of meeting the Sustainable Development Goals.

“The time to scale is now…Blended finance isn’t a silver bullet, it’s a tool, and it’s time we started using it.”

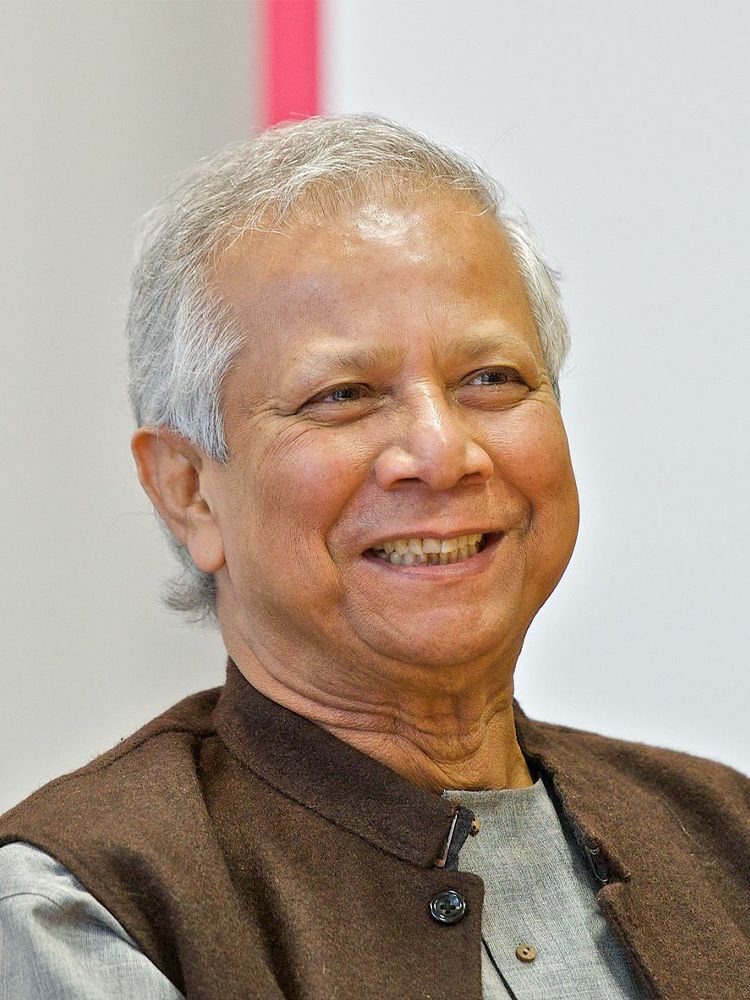

Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus pioneered microfinance in Bangladesh

Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus pioneered microfinance in Bangladesh

Sustainable investments could help expand projects like this rural solar programme in India

Sustainable investments could help expand projects like this rural solar programme in India

What is blended finance?

Blended finance is the use of catalytic capital from public or philanthropic sources to increase private sector investment, for example, in developing countries to realise the Sustainable Development Goals.

It can involve a broad range of different investors, from multilateral development banks and development finance institutions, to commercial investors, development agencies, impact investors and philanthropic organisations.

In 2020, according to The State of Blended Finance by Convergence, blended finance transactions across the world reached $4.5bn, although this was 50% down on the $11bn invested in 2019. Over the past five years, blended finance flows averaged around $9bn per year.

This research reveals that blended finance flows are not on track to mobilise the “billions to trillions” required to fill the SDG financing gap by 2030. However, researchers believe the potential for blended finance to scale is huge. The potential to scale, they say, depends on “the crowding-in of significant volumes of financing towards the SDGs, particularly private sector financing. Specifically, there is a need for more transactions that are at least $100 million in size”.

Across the Asia-Pacific region there is a huge amount of expertise in putting blended finance into practice. AVPN is playing a key role in co-ordinating Asian leaders – particularly through its Asian Impact Leaders Network – to submit their experience, research and knowledge to the G20 process.

As this article was published on 23 May 2022, a meeting of the G20 Development Working Group, which focuses on issues affecting developing countries and the SDGs, took place, hosted by the Indonesian Ministry for National Planning (known as Bappenas). The focus of the meeting was how to “scale up blended finance and private finance to reach the last mile”. AVPN highlighted results of a consultation with its members about the role that philanthropy could play in blended finance instruments.

Ibu Vivi Yulaswati is senior adviser to Indonesia’s minister of national development and planning and leads the Development Working Group. Like Professor Bambang, she is a member of the Asian Impact Leaders Network. She explains that a key focus of the group’s work on blended finance is to take the concept forward to its next stage. “Through the G20 Development Working Group, we want to discuss how to create ‘blended finance 2.0’,” she says. This means attracting more private sector finance, developing a widely adopted common framework, and measuring its impact more effectively.

There is also the opportunity for think tanks and other researchers to submit their thoughts via the G20’s T20 taskforces. Taskforce 9 of the T20 focuses specifically on global co-operation for the financing of the SDGs and its co-chair Abha Thorat-Shah, executive director, social finance, at the British Asian Trust, is currently working through a number of papers bringing in dozens of ideas about how to increase the use of blended finance and other sustainable finance instruments.

From Thorat-Shah’s point of view, the characteristics of collaboration and innovation that blended finance projects bring are a winning formula.

One of the outcomes of the 2020 G20 meeting in Italy was a G20 Sustainable Finance Roadmap, and the G20 Sustainable Finance Working Group is taking this forward with the aim of promoting a green and inclusive economy and achieving sustainable development. AVPN will this month provide the group with research into the barriers that its members have faced in their efforts to develop and scale sustainable finance instruments in emerging markets and developing economies.

AVPN’s annual global event in June brings another opportunity for the blended finance conversation to move forward. It’s an official side event of the G20 and AVPN is the government’s official impact partner. The event will, says Ace, provide a platform for several of the key issues around finance to be discussed.

Abha Thorat-Shah of the British Asian Trust is assessing papers on sustainable finance to submit to the G20

Abha Thorat-Shah of the British Asian Trust is assessing papers on sustainable finance to submit to the G20

Blended finance in practice:

the Skill Impact Bond, India

Millions of Indians have lost their jobs during the Covid-19 pandemic with young people and women hit the hardest. In response, the British Asian Trust and partners launched the Skill Impact Bond in October 2021 with the aim of boosting the skills of 50,000 young people in India over four years.

Impact bonds are results-based contracts that use philanthropic or private money to fund public services, often allowing innovations to be tested for scale or systems change. If the programme achieves its aims, the investors get their money paid back, but if the aims are not met, the investors lose their money.

The bond brings together an international coalition of public, not-for-profit and private sector players. The aim is to provide the young people (more than 60% of whom are women and girls) with vocational training and help them into jobs in the retail, apparel, healthcare and logistics sectors.

This impact bond’s funders take different roles. The ‘risk investors’ are India’s National Skill Development Corporation and the Michael and Susan Dell Foundation which have together committed US$4m as upfront working capital to the service providers to run the programme.

The ‘outcome funders’ are The Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, HSBC India, JSW Foundation and Dubai Cares. Together they have donated US$14.4m. If targets are met (as measured by an independent evaluator), the ‘risk investors’ are able to recover their capital and earn a return at the end of the project.

The programme is delivered by five local training providers.

Abha Thorat-Shah of the British Asian Trust says: “The impact bond approach brings an entrepreneurial mentality, private sector dynamism and collaborative approaches to global development challenges and ultimately transforms these into an investable opportunity rather than a problem.”

Among all the issues fighting for the G20 leaders’ attention, what chance does pushing forward work to support blended finance and sustainable finance have?

From Thorat-Shah’s point of view, it’s important to be realistic. “For example, if a country like India really embraces blended finance, it could have a huge impact as it can set the benchmarks and good practice for wider adoption and replication,” she says. However, she points out that it’s a long journey: “While India is already starting to do this, for it to become more mainstream, regulatory barriers need to be addressed, projects need to be designed with scale and sustainability in mind, and local governments need to buy into the advantages of these approaches.”

She emphasises that simple, scaleable models should be created to appeal to the private sector. “You need to cut away the over-complicated stuff and be nimble,” she says.

For Professor Bambang, his ministerial experience means that he knows that a strategic approach is key. He says that the world’s development banks must really get on board. “If we can get their commitment to be the executors, I believe the support of all the members of the G20, especially the advanced economies, will be there,” he says.

What’s more, he adds, a long-term view must be taken. In his role as co-chair of the T20, he says he has already started negotiating with India to ensure that conversations are taken forward during next year’s G20 negotiations.

“Yes, it’s a slow process,” says Thorat-Shah. “Yes, it’s hard. But, yes, it’s a big opportunity.”

Photo credits: ‘Barefoot solar engineer' in India: Abbie Trayler-Smith/Panos Pictures/Department for International Development reproduced under a creative commons licence; Indian students courtesy British Asian Trust

This immersive feature was produced by Pioneers Post in partnership with AVPN. Stay tuned for more articles exploring Asian leaders’ work to build a sustainable, just, inclusive and resilient future.

Get in touch if you'd like to tell your story.

J O I N T H E I M P A C T P I O N E E R S

SUPPORT OUR IMPACT JOURNALISM

As a social enterprise ourselves, we’re committed to supporting you with independent, honest and insightful journalism – through good times and bad.

But quality journalism doesn’t come for free – so we need your support!

By becoming a fully paid-up Pioneers Post subscriber, you will help our mission to connect and sustain a growing global network of impact pioneers, on a mission to change the world for good. You will also gain access to our ‘Pioneers Post Impact Library’ – with hundreds of stories, videos and podcasts sharing insights from leading investors, entrepreneurs, philanthropists, innovators and policymakers in the impact space.