When fashion faces the future

The biomaterials startups going back to nature

Our demand for new clothes is seemingly unstoppable. That’s bad news for the planet: the fashion industry already causes up to 10% of global greenhouse gas emissions, and that's set to rise sharply. But, as shoppers wake up to this reality – and as regulators clamp down – the inventors of new, nature-derived materials have an opportunity like never before. Can these innovators convince price-conscious consumers, investors and retailers to take a leap into the unknown?

Sunglasses made from coffee grounds. Designer dresses made from fungi. Trainers made from grape leather. Your latest purchase might make for a quirky story, but can these wholesome-sounding creations really transform fashion?

Some would say there isn’t a choice. Materials today account for 91% of the fashion industry’s total emissions through their extraction, processing and production. Synthetic ones are a major culprit, making up 69% of all materials used in clothing. But natural materials can also cause problems – large-scale cotton cultivation, for instance, involves high water consumption, pesticide use and soil degradation.

A materials “revolution” might just bring us back full circle to a time when everything we used was natural. When demand soared, “humanity turned to chemistry, switching the natural for quick and easily synthesised man-made materials”, Suzanne Lee, a biomaterials expert and CEO of the design agency Biofabricate, told Sleek Mag in 2023. “Now, we have the tools to make the same things – without killing the animal, without cutting down the tree. We can programme biology to do it in a much more efficient way using minimal and renewable resources.”

Biomaterials is a broad term, but generally refers to finished materials or end products that either incorporate biomass feedstocks (that is, non-petroleum material derived from plants or animals) and/or are produced through biological processes. In some cases these biomaterials are biodegradable.

That breadth causes confusion, says Katrin Ley, managing director of Fashion for Good, an Amsterdam-based initiative created by the Laudes Foundation that supports innovation in the fashion industry. A general assumption is that “bio” means good or sustainable, but it’s not that simple – meaning “huge potential for greenwashing”, says Ley. For example, the biobased content of biomaterials can vary widely, from just 10% to 100%. And a biomaterial like 100% biobased PET, made entirely from biomass rather than petroleum, is chemically identical to conventional PET and can take hundreds of years to break down in landfill. Transparency and education are vital, according to Fashion for Good, which in 2020 published a lengthy report alongside Biofabricate, setting out the basics on biomaterials, and aiming to address the “widespread ignorance” among consumers, fashion brands – and even some material innovators themselves.

The race is on to create clothing that is less harmful to our environment.

The race is on to create clothing that is less harmful to our environment.

Experts hope to see a "materials revolution" – involving innovators like Bananatex, which uses abacá, a kind of banana plant. (©Lauschsicht)

Experts hope to see a "materials revolution" – involving innovators like Bananatex, which uses abacá, a kind of banana plant. (©Lauschsicht)

The term "bio" suggests a product is sustainable or good, but that's not always the case, says Katrin Ley from Fashion for Good.

The term "bio" suggests a product is sustainable or good, but that's not always the case, says Katrin Ley from Fashion for Good.

FASHION IN FIGURES

Clothing production across the world doubled between 2000 and 2014

Materials account for 91% of the fashion industry’s total emissions through their extraction, processing and production

Synthetic materials account for 69% of all textiles – requiring more oil than the annual consumption of Spain

Global investment in biomaterials companies reached a record high of $1.7bn in 2022

Nearly 13m tonnes of next-gen materials could enter the market by 2030, representing around 8% of the total fibre market (up from almost 1% today)

McKinsey Sustainability; World Resources Institute and Apparel Impact Institute; Changing Markets; World Bio Market Insights; Boston Consulting Group/Fashion for Good

Biomaterials were booming a few years ago: investment in biomaterials companies reached a record high of $1.7bn in 2022. The next two years saw a significant drop – reflecting trends in the wider clean tech sector. But this year looks set to climb back up, with $392m invested in the first quarter of 2025. If that continues, it could be transformative.

This growth has caught the attention of international law firm Hogan Lovells, whose ‘HL BaSE’ practice supports business and sustainable enterprise. “We are seeing more and more startups working on biomaterials – it gives you a new appreciation for the resources we already have and how we can use them in new ways,” says Fenella Chambers, lead counsel at HL BaSE. A sound legal footing is key for these innovators, she adds: for startups keen to make an impact but short on cash and human resources, it can be tough to ensure the fundamentals, such as intellectual property rights.

Few biomaterials innovators have progressed far beyond the research and development stage. “Many, many startups – I’ll say the majority of them – fail in the lab-scale stage,” says Ankur Agarwal, head of VC investments at PDS Ventures, which focuses on textiles innovation, sustainability and technology. “When they test those materials in a commercial or industrial setup… the results are very different.”

Fashion for Good points to an unrealistically high bar: man-made synthetics, based on cheap fossil fuels, have raised our expectations in terms of performance so that we expect any new material to offer features like strong colour fastness or extreme durability. But it is more complex to master consistent quality and scalability with biomaterials than with cheaper synthetics. It is also still very early stage. Media coverage of innovations has sometimes added to unrealistic expectations, by suggesting a material is already in use when in fact it is still in an experimental design phase.

Even when materials perform well outside the lab, startups face three key challenges, says Ley: demonstrating sufficient demand, achieving cost efficiencies and securing capital investment. And all of these relate to one crucial factor: a competitive price point.

“We are yet to see a consumer shift, or a consumer acceptance, to pay more for sustainable products,” says Agarwal, although he notes that rising interest in second-hand clothing at least demonstrates more awareness of the industry’s negative impact.

Learn more about the outdoor clothing companies going circular in our Good Stories podcast

Ley is similarly pragmatic. Support for sustainability does not always translate into buying decisions; ultimately, it comes down to: “Is the product desirable and does it hit a certain price point?” We cannot rely on the “small niche of very passionate, convinced consumers” to drive demand, she says.

Instead, Fashion for Good sees the biggest leverage point as the fashion industry itself, supported by regulations and policy. Enabling collaboration is “absolutely our secret sauce”, says Ley: this includes bringing groups of fashion brands and groups of innovators together to secure purchasing commitments that go beyond the industry’s typically short-term timelines. That sends a crucial “long-term demand signal” to potential investors.

Multi-year partnerships are becoming more common, according to Fashion for Good – with its support, in some cases, as in the pilot in which materials innovator Ecovative developed mycelium-based (the root-like structures of mushrooms) alternatives to leather and foam materials, teaming up with brands including shoe maker Vivobarefoot. Others include the “multi-year collaboration” announced earlier this year between sportswear brand Lululemon and a startup to use more biobased nylon.

But Agarwal points out that only a few brands are “inherently more forward-focusing and more future-proof”: he estimates that around 2%-3% of the brands and retailers that PDS Ventures works with partner with early-stage materials startups. For many, in the current economic climate, “it’s more about survival and margins”, he says. Outliers include high street brand Mango, which has created a small collection with Materra, a PDS Ventures investee that sources traceable and regenerative cotton.

Read our profile of award-winning circular fashion business, Elvis & Kresse

PDS Ventures has invested around 50%-60% of its $50m fund, which comes from the profits of its parent company PDS, a supply chain firm. In seeking new investees, potential to scale is crucial, says Agarwal. New materials derived from agri-waste may be interesting, but adequate supply of raw materials can be a block. Innovators proposing “drop-in solutions” – those that can fit easily into an existing supply chain – are more appealing than those requiring completely new facilities and significant capital expenditure. The target market (serviceable addressable market, or SAM) also needs to be large enough, and “startups should have an ability to at least capture 10% of the SAM over time to make it viable for both the company as well as investors,” Agarwal says. Serving multiple industries and uses, rather than only fashion clients, offers further opportunities: for example, NFW, which has created a leather alternative for fashion brands, has also worked with BMW on interiors for its cars.

The current political climate is not making things easier. US tariffs distract focus away from innovation and towards dealing with supply chain issues, says Ley, and the policy shift away from sustainability is a worry. Things are more positive in Europe, she says, where EU regulation, including on waste and transparency, has been instrumental in shaping the industry.

That may not stick, however. The EU has been accused by campaigners of “opening the door to rampant greenwashing” by watering down corporate reporting requirements; this week the European Commission halted talks on a law that would tackle fake “green claims”.

Yet some entrepreneurs want more, not less, regulation. “The rules of the game” need to change, says Hannes Schoenegger, who co-founded biomaterials startup Bananatex – otherwise genuinely sustainable alternatives will never be able to compete.

As to where the biomaterials market is likely to go in the coming years, Agarwal says it’s impossible to say. “We can’t even predict what’s happening a week from now… in this uncertain world, it’s more of a ‘wait and watch’ perspective.”

Startups experimenting with new materials are widespread – like Planet of the Grapes, which uses the waste from wine production.

Startups experimenting with new materials are widespread – like Planet of the Grapes, which uses the waste from wine production.

Man-made synthetics have raised our expectations of what materials can do – but they usually end up in landfill. (Freepik)

Man-made synthetics have raised our expectations of what materials can do – but they usually end up in landfill. (Freepik)

Fashion for Good supports innovators such as Ecovative, which has developed mycelium-based alternatives to leather.

Fashion for Good supports innovators such as Ecovative, which has developed mycelium-based alternatives to leather.

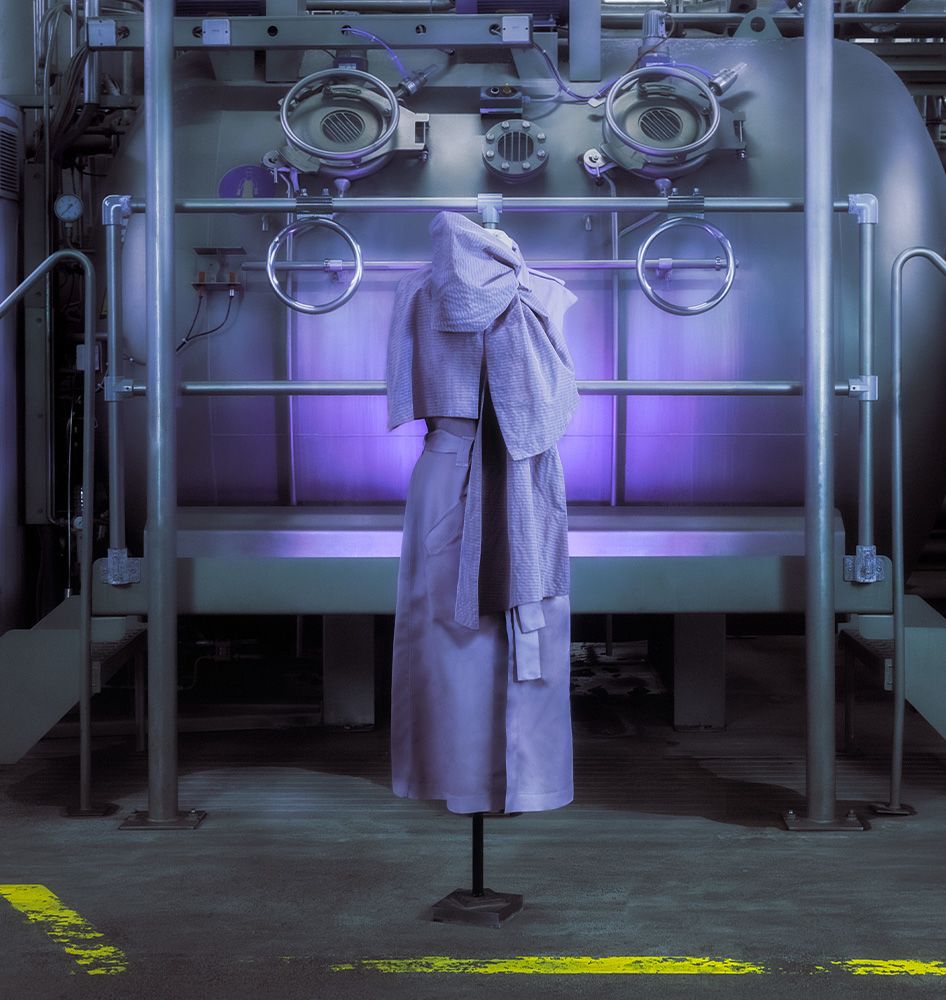

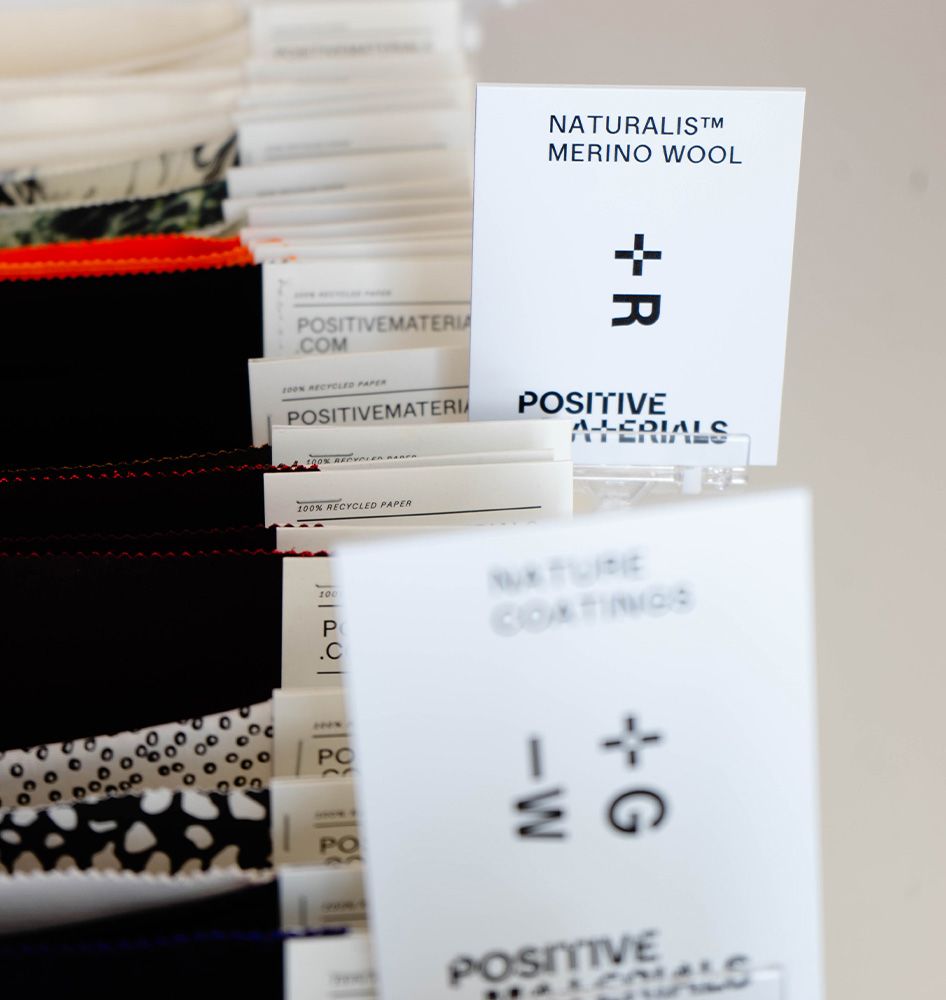

Positive Materials, part of the sourcing and manufacturing firm PDS Group, supports innovation in textiles and next-gen materials.

Positive Materials, part of the sourcing and manufacturing firm PDS Group, supports innovation in textiles and next-gen materials.

Biomaterials: a misleading term

Biomaterials

‘Biomaterials’ generally refers to finished materials or end products that are partly or fully derived from biological feedstocks – non-petroleum sources such as plants or animals – and/or are produced through biological processes. The term ‘biobased’ refers only to the origin of the feedstock, not the material’s biodegradability, bio-content level or method of production. As such, the ‘biomaterial’ label can be misleading: it does not indicate how ‘biological’ a material truly is, nor does it describe how it was processed.

Next-generation fibres or materials

This refers to novel and innovative fibres and materials with desired improved environmental and/or social outcomes when compared with conventional options; that are in early stages of commercialisation or development; and that require further technological advancement and cost optimisation for widespread adoption.

Source: Fashion for Good

“A lot of times, designers want the most sustainable product, but they don't understand the price of that.”

Seeking better answers: Bananatex

Hannes Schoenegger and his friends just wanted a functional, stylish all-rounder bag – one you could take to the gym, on your bike, on a business trip. Back in the mid 2000s, that didn’t seem to exist. So they decided to design it themselves.

That was the start of Qwstion, a Swiss bag brand founded in 2008 (Schoenegger, now CEO, is Austrian; his co-founders, both industrial designers, are Swiss). The name refers to their ethos of “questioning everything”: the materials, the design, a product’s end of life: “basically all of those norms – we tried to find better answers,” Schoenegger says.

The first question was how to make a bag without adding to the world’s “mountain” of plastics. They tried cotton: not strong enough, too many environmental problems. Then hemp: a slow, two-year process of figuring out supply chains – only to discover that the knowhow and factories for spinning yarn no longer existed in Europe. They tried linen. They tried bamboo fibre. Then they stumbled upon abacá – a kind of banana plant, grown mostly in the Philippines.

“We immediately saw the potential, because the fibre itself is quite similar to hemp. It grows without attention. It’s happening in the forests, and there’s no water and no chemicals [needed]. And it grows in Asia, where there’s still a lot of knowhow in spinning and weaving,” says Schoenegger.

While abacá fibre had long been used to make rope, as well as paper and tea bags, it had never been turned into a fine enough yarn needed to make a bag. Together with a yarn specialist and a weaving partner in Taiwan, Qwstion spent three years figuring that out. The result was Bananatex, described as “the world’s first durable, biodegradable and plastic-free fabric made purely from regeneratively grown abacá banana plants”. Its first bags were shown off in 2018.

Above: the Bananatex life cycle

Above: the Bananatex life cycle

Research and development was entirely funded by Qwstion – something no business advisor would have recommended them doing, says Schoenegger. But it felt “like the right thing” to do. He and his co-founders also decided to make their innovation open-source – meaning other companies could request samples and details of the manufacturing process.

“We didn’t want it as a commercial asset for ourselves, because we wouldn’t cause a lot of positive change if we were only to use it ourselves,” he says. Requests poured in – from fashion, sportswear and footwear companies (and even one cigarette company).

The interest was hugely encouraging, and in 2020, the co-founders created a small spinout company, also called Bananatex, to develop more fabrics of different weights and weaves. Designers Stella McCartney and Balenciaga and high street brands H&M and Cos are among those who have sold items made with Bananatex.

Rules of the game

The company is supported by Fashion for Good, and it has had investment from a Swiss private investor and Parley for the Oceans, an environmental organisation. But Schoenegger isn’t celebrating yet: sure, it has proven the concept, but Banantex won’t be commercially successful, he says, until 10 or 20 major brands are consistently using its fabric. For that to happen, we need widespread change to the way our economy works.

“The rule of the game is: you have to make profits, and every company has to do that,” he says. Without incentives to use sustainable and circular materials, and requirements to factor in the true environmental cost of the products they sell, alternatives like Bananatex will never be able to compete long term.

“To be very honest, I doubt that next-gen materials can scale as long as the rules of the game are not changed,” he says.

Read our interview with Patagonia's Matthijs Visch: ‘We do walk away from business we don't believe in’

And, after the excitement of a few years ago, the sector is now facing “quite a difficult time”, according to the co-founder. “The future materials industry needs a lot of support... We see innovators closing down, and others cancelling their funding rounds, and not being able to scale.” He cites global conflict, inflation and political shifts – as well as unmet expectations among a few larger companies, which may have prompted investor hesitation. Public awareness of alternative materials is still surprisingly low, Schoenegger believes.

But materials like Bananatex have significant potential, he says. Abacá grows only in the Philippines, Costa Rica and Ecuador, but it could be planted in any tropical region, contributing to reforestation alongside other plants. Ultimately, Schoenegger estimates that – with sufficient investment in processing facilities – it could replace up to 5% of cotton in use today. Given the dominance of cotton, that’s no small amount.

In the meantime, working with nature continues to reveal startling and sometimes advantageous surprises. While developing Bananatex, the team discovered that plants growing in the northeast of the Philippines yielded stronger fibres than those elsewhere – because they had evolved to withstand the more frequent typhoons there. “There’s so much to learn,” Schoenegger says.

Matthias Graf, Christian Paul Kägi and Hannes Schoenegger co-founded the brand Qwstion – named after their ethos of "questioning everything".

Matthias Graf, Christian Paul Kägi and Hannes Schoenegger co-founded the brand Qwstion – named after their ethos of "questioning everything".

Schoenegger and his colleagues tried various materials before they stumbled upon abacá, a kind of banana plant grown mostly in the Philippines. (©Lauschsicht)

Schoenegger and his colleagues tried various materials before they stumbled upon abacá, a kind of banana plant grown mostly in the Philippines. (©Lauschsicht)

Abacá is appealing because it grows by itself in the forests in Asia, "where there’s still a lot of knowhow in spinning and weaving". (©Lauschsicht)

Abacá is appealing because it grows by itself in the forests in Asia, "where there’s still a lot of knowhow in spinning and weaving". (©Lauschsicht)

Research and development was funded by Qwstion. It unveiled the new Bananatex bag in 2018 (©Lauschsicht)

Research and development was funded by Qwstion. It unveiled the new Bananatex bag in 2018 (©Lauschsicht)

Abacá could be planted in any tropical region and – with sufficient investment in processing facilities – could replace up to 5% of cotton in use today, according to Bananatex. (©Lauschsicht)

Abacá could be planted in any tropical region and – with sufficient investment in processing facilities – could replace up to 5% of cotton in use today, according to Bananatex. (©Lauschsicht)

Fed up with fast fashion:

Planet of the Grapes

Samantha Mureau started a career in the fashion industry in the late 1990s, working in London as a buyer for retailers including high street brand Topshop, before launching her own consultancy. She recalls a time of “very fun fashion”.

Then came the era of ultra-cheap, fast fashion. From 2008, as the financial crisis hit, the industry wasn’t very fun any more: “Everyone was just looking the same, because everything was starting to be dictated by price,” she remembers. Fed up, she left the industry and began a new life in the south of France. Then in 2013, a tower block in Bangladesh that housed factories for low-price western brands collapsed, killing more than 1,100 people. The Rana Plaza building had previously been found to be unsafe but workers had been ordered to continue regardless. Mureau was shocked: “Why are people now dying for our clothes?” she thought. “That’s when, for me, the fashion industry really became very flawed.”

Shortly afterwards, a documentary called “The True Cost” revealed the social and environmental impacts of the garment industry – and it featured Topshop. “I was like, ‘wow, ok, I’ve got to do something now’,” recalls Mureau.

Rather than creating her own sustainable fashion brand, she decided to focus on a much earlier stage of the process: creating a new kind of material that would interest sustainability-first designers. By this time, she was living in the heart of wine country in Provence, France, where she came across an under-used, yet abundant by-product: grape marc, which is the leftover waste after grapes have been pressed to make wine.

Mureau started experimenting with grape marc in her kitchen, before piquing the interest of scientists at the University of Lyon. She convinced them to help her create a new material from grape marc that could be used as an alternative to leather or other materials.

To create the new material (which is yet to be named) the grape marc is dried, then ground, and turned into a paste that is spread over a backing, usually made of cotton, polyester or nylon, which gives it strength and durability. The end product is 80% plant-based bio-material, although formulations differ according to the end use – this includes clothing, accessories and interior design items like bar stools.

Although Mureau’s company, Planet of the Grapes, is described as “designed for future circularity”, the material is not biodegradable. But Mureau says a long-term goal is compostability; in the meantime, the company is looking into other ways of limiting its footprint, such as using recycled nylon backing.

Reaching industrial scale

Planet of the Grapes was incorporated in 2021 as a société par actions simplifiée (SAS), the French equivalent to a limited company. It has so far had funding from business accelerator Fashion Revolution, the French public bank BPI, and a local programme supporting circular design in Provence. It has also had pro bono legal support from the law firm Hogan Lovells.

Mureau sources the grape waste from local organic or bio-dynamic vineyards, where she personally helps with the harvest and gets the waste in exchange for her work, and she prides herself on knowing each of these vignerons by name. As the business grows she plans to buy grape marc from vineyards that would otherwise discard it.

Once she has prepared the grape waste, she sends it to a supplier in Italy that processes it into rolls of material. What started as tiny samples can now be produced at industrial scale – recently achieving a production run of 300m by 1.5m rolls – meaning the product is now ready to be marketed to upmarket fashion and design businesses.

New generation

Planet of the Grapes is not just about selling a product: as part of several consortia of sustainable material innovators across Europe, it is also advocating for changes to the fashion industry as a whole.

A major issue is price: creating a whole new material – rather than a simple animal leather alternative, which could be entirely made of plastic – takes time and effort, which is not always understood. “If you’re talking to designers, a lot of times they want the most sustainable product, but they don’t understand the price of that,” Mureau says.

She adds the “extraordinarily cheap prices” of fast-fashion brands such as Shein and Temu mean consumers now have unsustainable expectations. “How can you ever wear a piece of clothing that’s cheaper than your sandwich that you’ve paid for?” asks Mureau. “I think we’ve forgotten the right price of clothes.”

One solution lies in engaging the new generation, so Mureau teaches sustainable fashion programmes in universities to show young designers that it is possible to create clothes in an environmentally-friendly way. “I love fashion,” she says, “so I wanted to help the next generation coming through to do it differently.” And, as new brands emerge that seek to limit their environmental impact, they will challenge conventional forms of production, she hopes. “New blood coming through in the industry may help,” she says.

From the perspective of Planet of the Grapes, collaboration with individual designers, brands and retailers will be key. Mureau hopes big brands will be open to partnering with innovators like her as they see increasing demand for sustainable products, and as new and improved materials emerge.

It might come sooner than we think: luxury fashion house Hermès, renowned for its leather work since it began making saddles and harnesses nearly two centuries ago, has already produced a handbag made from mushrooms.

Former Topshop buyer Samantha Mureau became disillusioned with the negative impact of fashion, and decided to look at alternative ways of creating clothing.

Former Topshop buyer Samantha Mureau became disillusioned with the negative impact of fashion, and decided to look at alternative ways of creating clothing.

The waste from wine production is ground, dried and turned into a paste, and then spread over a backing to create material.

The waste from wine production is ground, dried and turned into a paste, and then spread over a backing to create material.

Planet of the Grapes material has been used to make accessories and clothing, made by designers Eloine LeMouel, Rouslana Andriyanova, LLUK and Isabelle Megret Renner.

Planet of the Grapes material has been used to make accessories and clothing, made by designers Eloine LeMouel, Rouslana Andriyanova, LLUK and Isabelle Megret Renner.

Four more ways to rethink fashion

NFW aims to replace single-use and non-recycled plastic with its natural-based materials. It has created “the world’s first 100% biobased leather alternative” – used for footwear and accessories, and by designers such as Karl Lagerfeld and Ralph Lauren. NFW was shortlisted for the 2024 Earthshot Prize.

Ecovative creates new technologies using mycelium, the root-like structures of mushrooms, to create biodegradable materials that can replace materials commonly made of plastic. Originally focused on packaging – with partners including IKEA – Ecovative has since been developing foams and leather-like hides for fashion and footwear.

Nature Coatings turns wood waste into high-performing black pigments that can replace petroleum-based carbon black pigments (used for a range of things, from tyres to textiles). Nature Coatings’ innovation contains no toxic substances, and is manufactured in a way that emits negligible amounts of greenhouse gases.

Sequins are normally made of plastic and often contain toxic material that ends up in landfill or in the oceans. Radiant Matter has developed a biodegradable alternative made from tree cellulose – and used by designer Stella McCartney.

Top photo: ©Yves Bachman/Bananatex. Photos supplied by Fashion for Good, PDS Ventures, Qwstion/Bananatex and Planet of the Grapes, unless otherwise specified. Additional stock imagery by Freepik.

Words by Anna Patton and Laura Joffre. Design by Fanny Blanquier.

Help Pioneers Post understand its impact by answering this short survey:

This immersive feature was produced by Pioneers Post in partnership with Hogan Lovells and HL BaSE, the firm’s impact economy practice. The story is free to read thanks to the support of Hogan Lovells.

Get in touch if you'd like to tell your story.

J O I N T H E I M P A C T P I O N E E R S

SUPPORT OUR IMPACT JOURNALISM

As a social enterprise, we work hard to ensure our stories are as widely accessible as possible – that’s why all our stories are free to read for one week after publication.

After that, you’ll need to be a member to view them. Membership of Pioneers Post means unlimited access to thousands of interviews, news stories, features, expert insight and explainers, all focused on helping you to do good business, better.

It also means you’re helping to sustain our journalism. As a Pioneers Post reader, we know you value thoughtful and thorough reporting on the impact economy – but you also know that producing quality work doesn't come free. We rely on our members to sustain our journalism – so please consider investing in our mission.