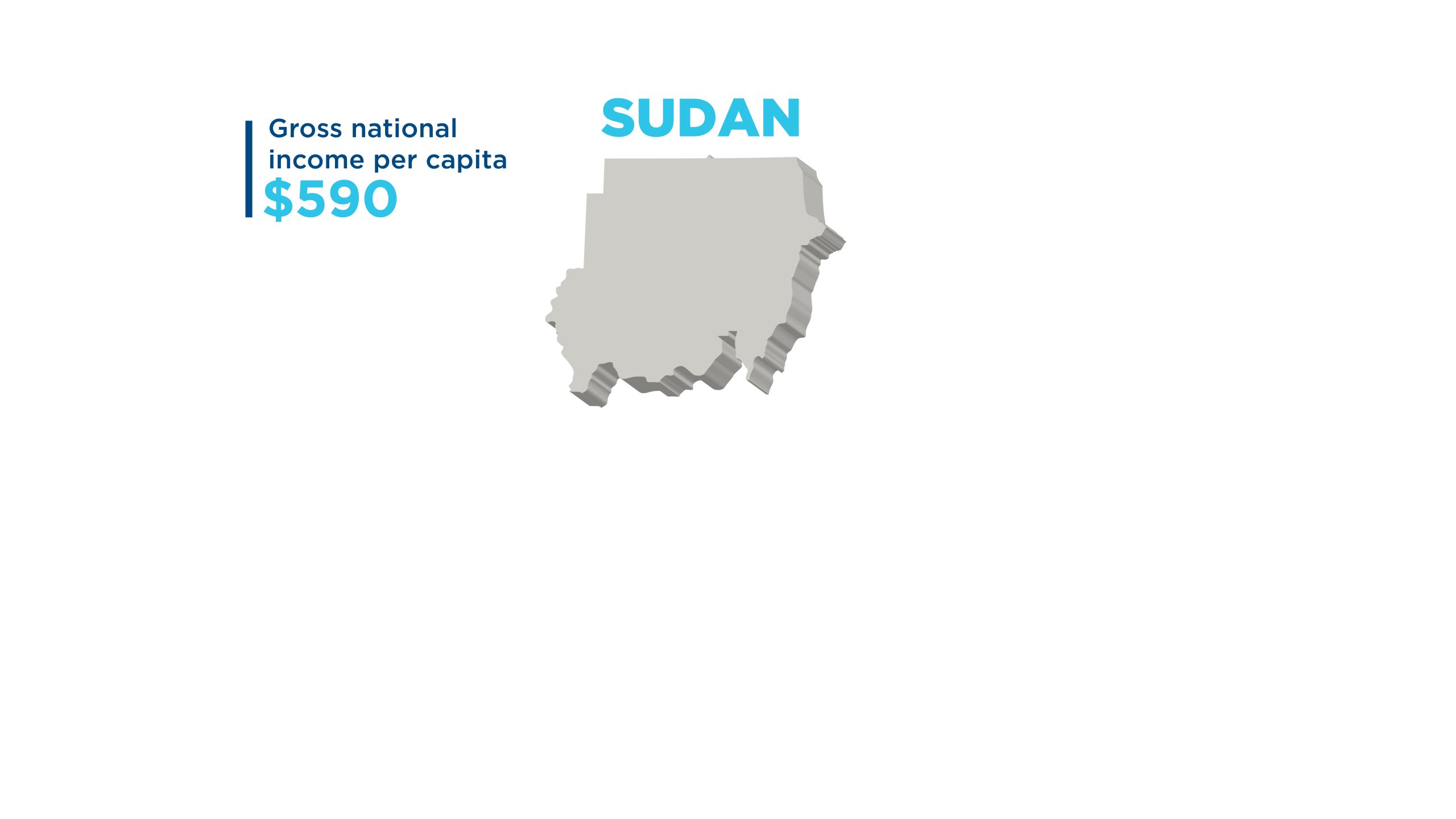

Global Focus: Sudan

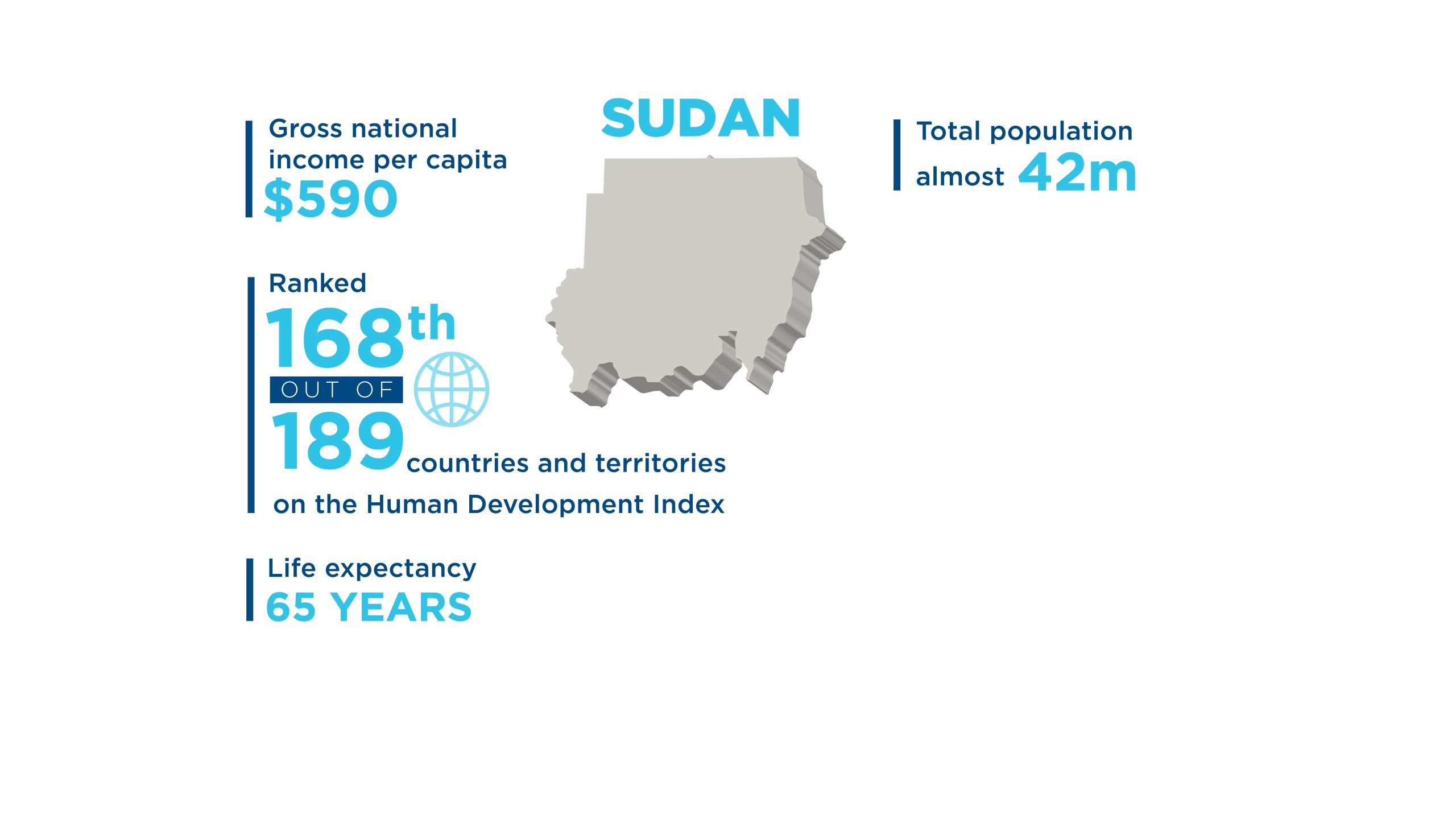

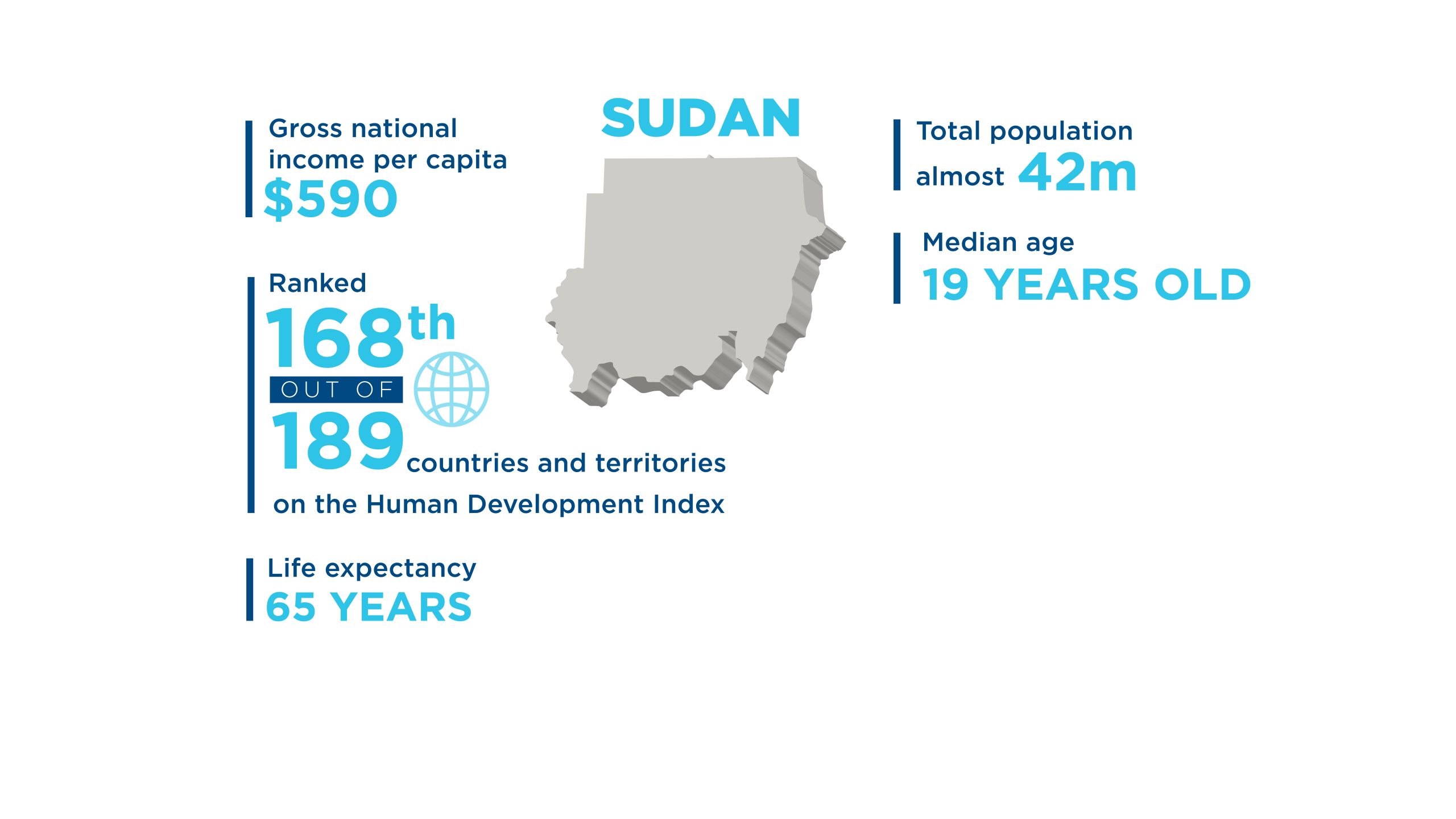

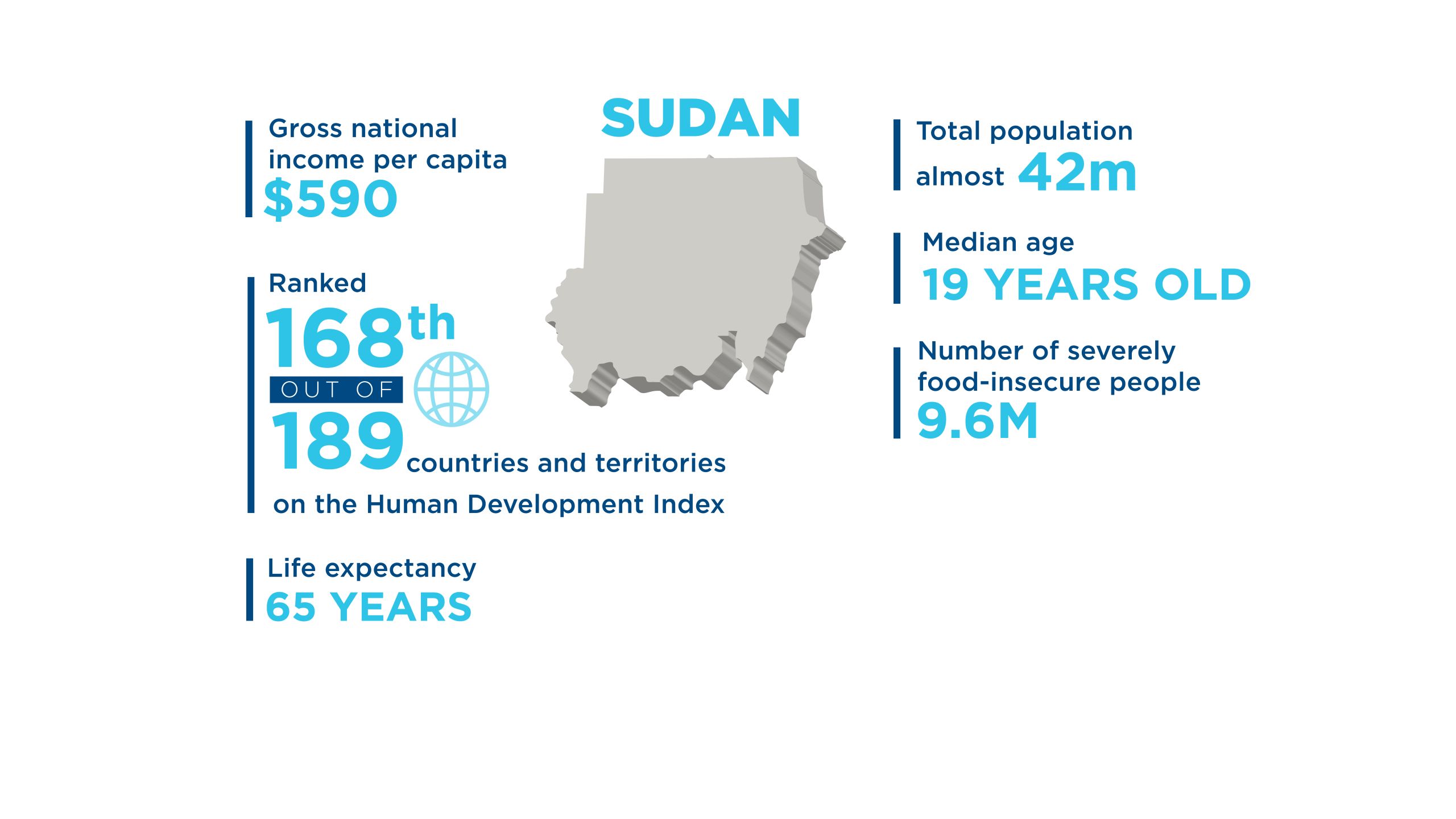

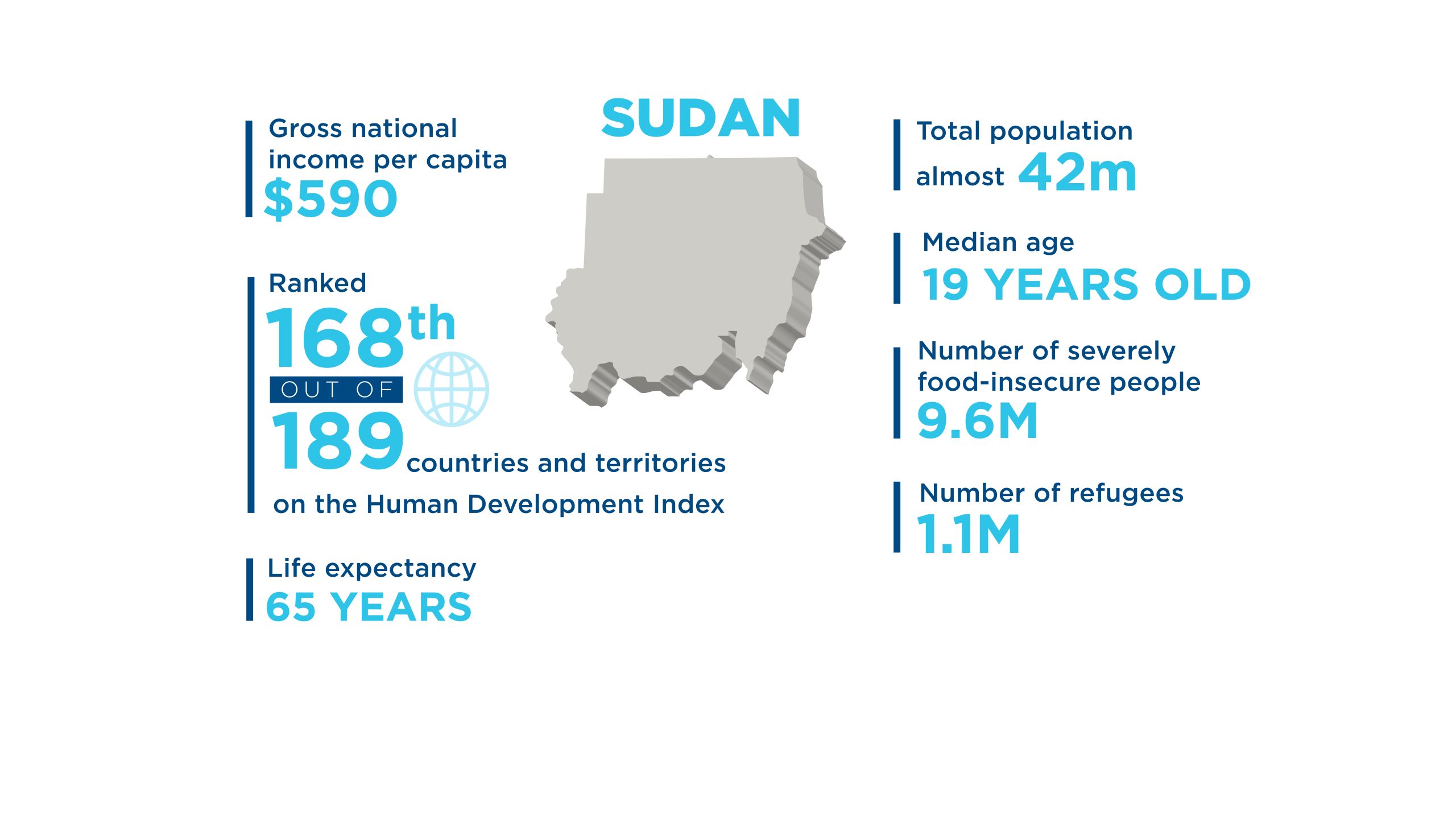

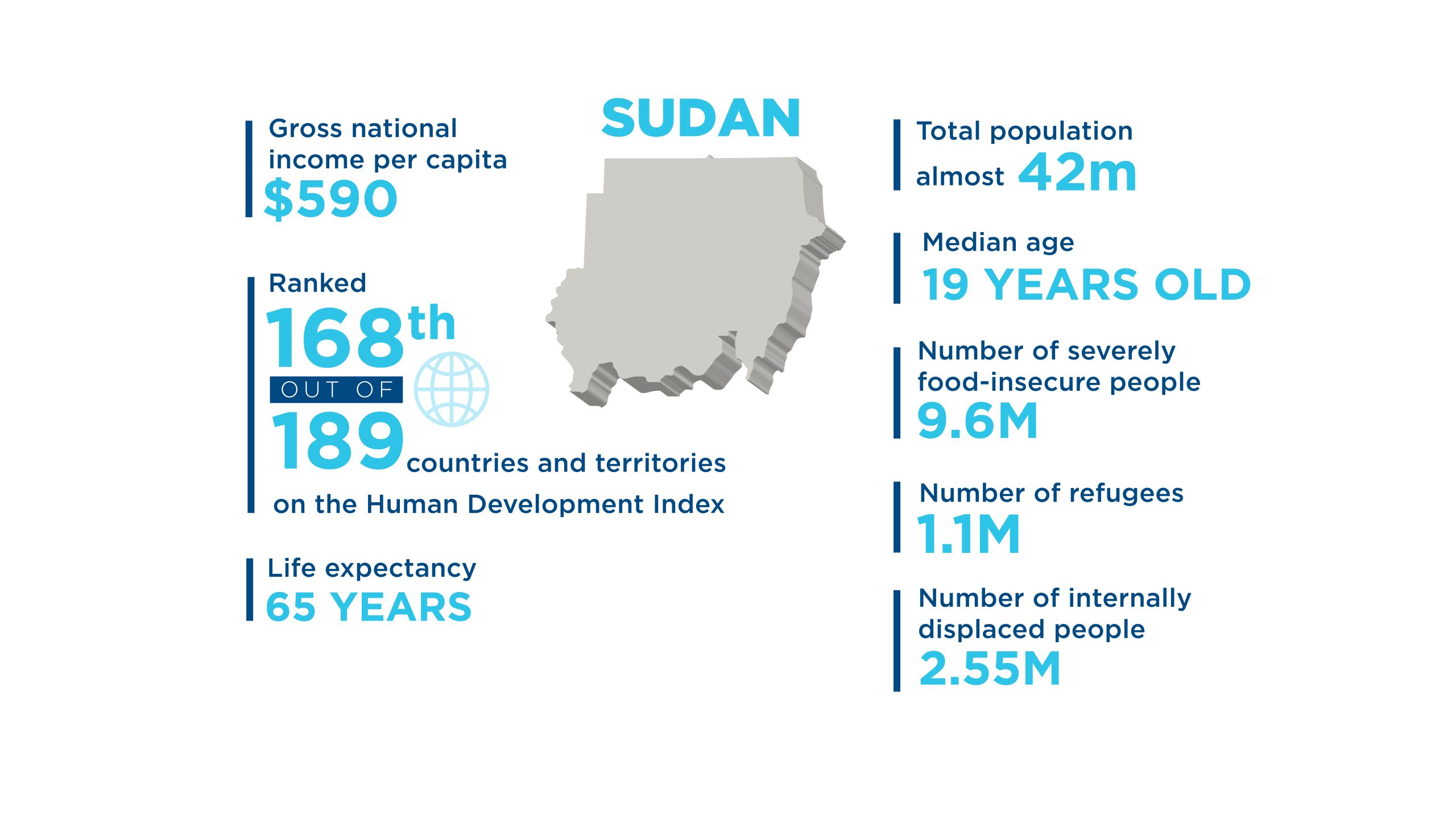

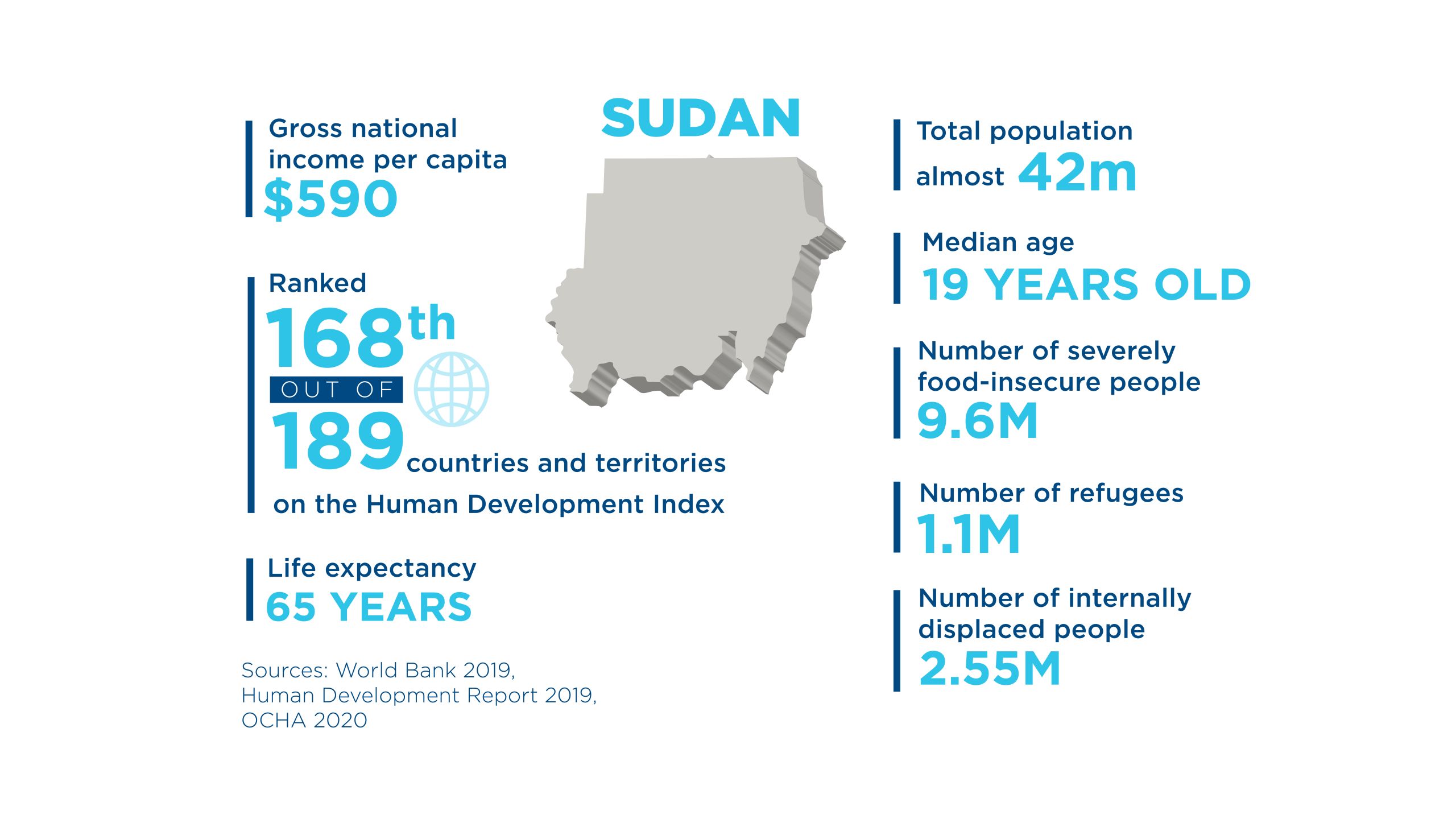

Sudan has a turbulent history and – in spite of a new government taking power after last year's revolution – the Covid-19 pandemic, continuing unrest and a new influx of refugees mean stability is still out of reach. Could Sudan's new generation of social entrepreneurs help rebuild the country? In Khartoum Pioneers Post talks to some of them about their ambitions for the future.

Lit by a shaft of evening sun, 21-year-old Anda Kamal Yousif quietly talks about Sudan’s 2019 revolution which ousted the Islamist general Omar al-Bashir after a 30-year dictatorship.

She describes how she and her friends joined thousands of others at an anti-government protest – a sit-in – in April which lasted for weeks. They took the instruments and the sound system from Mellow Art Space, the social enterprise that she helps to manage, to join in with all the other music, singing and dancing.

One day, when the protestors were sheltering from rain inside a hall, armed forces – no-one is still quite sure under whose command – attacked.

“One of our friends, he was a doctor…he went out to stop them and say there are kids inside, please don’t fire,” she says, unflinchingly. “He was taken away in front of everyone’s eyes. He was killed.”

Anda Kamal Yousif: "He was taken away in front of everyone's eyes. He was killed"

Anda Kamal Yousif: "He was taken away in front of everyone's eyes. He was killed"

Social entrepreneur Wissam at Pioneers Post's communications training

Social entrepreneur Wissam at Pioneers Post's communications training

Social entrepreneurs discuss their 'elevator pitches' in Pioneers Post's communications training

Social entrepreneurs discuss their 'elevator pitches' in Pioneers Post's communications training

A quiet courage runs through the young Sudanese people we meet in Khartoum. Less than a year before Pioneers Post managing editor Anna and I visit in March 2020, they were part of a movement of thousands of people who risked their lives to force change in a country whose people had been suffering for decades under a hardline regime.

We are in Sudan to deliver communications training to social entrepreneurs and to talk to journalists about the global social enterprise movement. At the same time, Anna and I have the opportunity to talk to many of the entrepreneurs about the huge political changes that have taken place over the past couple of years, and how they as social entrepreneurs see their role in the country whose democracy they helped to create.

Running alongside the courage that we see in Anda and others, we notice enormous optimism. They all emphasise how they believe they are working towards a “new Sudan” through the enterprises that they have founded.

As Hatim Mubarak Hassan, the head of the fledgling Sudan Social Enterprise Association tells us: “We’ve done our political change, now is the right time to do our social change.”

Yet on 13 March, the day we fly out of Khartoum, news was breaking of Sudan’s first case of Covid-19. Over the coming months, lockdowns will be enforced in efforts to control what will become a global pandemic, and the optimism we see among these social entrepreneurs will be sorely tested.

We've done our political change. Now is the right time to do our social change

Stability and prosperity have been out of reach for most Sudanese since the nation declared independence from British and Egyptian rule in 1956. “For most of its independent history, the country has been beset by internal conflicts,” says the World Bank. A succession of civil wars, military coups and rebellions mark its timeline.

In 1989, General Omar al-Bashir seized power, and violently quashed any political opposition, eventually transforming the country into a totalitarian one-party state. Strict social and religious rules meant that women risked a flogging for wearing trousers, dancers were forced to practise in secret and musicians had sound systems confiscated.

US sanctions were imposed in 1997 when the Clinton administration named it as a state sponsor of terrorism, preventing foreign investment and debt relief. President Trump’s recent pledge to lift the sanctions comes at a crippling price – millions of dollars of compensation for victims of terrorist attacks – and any effects will take years to filter through to the people.

A peace agreement signed in 2005 allowed the southern part of the country to declare independence, becoming South Sudan six years later. This might have helped resolve longstanding internal conflicts, but it was a huge economic blow as the south took the oil industry with it, which had provided more than half of the government’s revenue. Economic turbulence followed with double-digit inflation and spiralling prices. In 2018, the government removed subsidies and the resulting rise in the cost of bread and fuel led to widescale protests. By December that year, the revolution had begun.

On 6 April 2019, demonstrators occupied the square in front of the military government’s headquarters. A few days later al-Bashir was out, and a council of army generals assumed power. But demonstrators stayed put and demanded a civilian government and democratic elections, staging a peaceful, round the clock sit-in. As a BBC Africa Eye report says: “it also became a celebration of new-found freedoms and a festival of Sudanese culture” with the music and dancing that Anda of Mellow Art Space describes.

It didn’t all run peacefully. Anda describes one attack on protestors in April, But on 3 June, the military massacred protestors in a much bigger, orchestrated attack.

The protestors weren’t thwarted though and in August 2019 a transitional government was agreed upon – a power-sharing agreement between the military and civilian forces, led by civilian prime minister Abdalla Hamdok.

President Omar al-Bashir led Sudan for 30 years. Here he is welcoming Rwanda's President Paul Kagame to Sudan in 2017

President Omar al-Bashir led Sudan for 30 years. Here he is welcoming Rwanda's President Paul Kagame to Sudan in 2017

Women played a key role in the 2019 revolution, often making up 70% of the protestors

Women played a key role in the 2019revolution, often making up 70% of the protestors

The 2019 protesters were eventually victorious

The 2019 protesters were eventually victorious

Abdalla Hamdok became Sudan’s civilian prime minister in late 2019

Abdalla Hamdok became Sudan’s civilian prime minister in late 2019

Rabah Hassan, who led drummers during the revolution

Rabah Hassan, who led drummers during the revolution

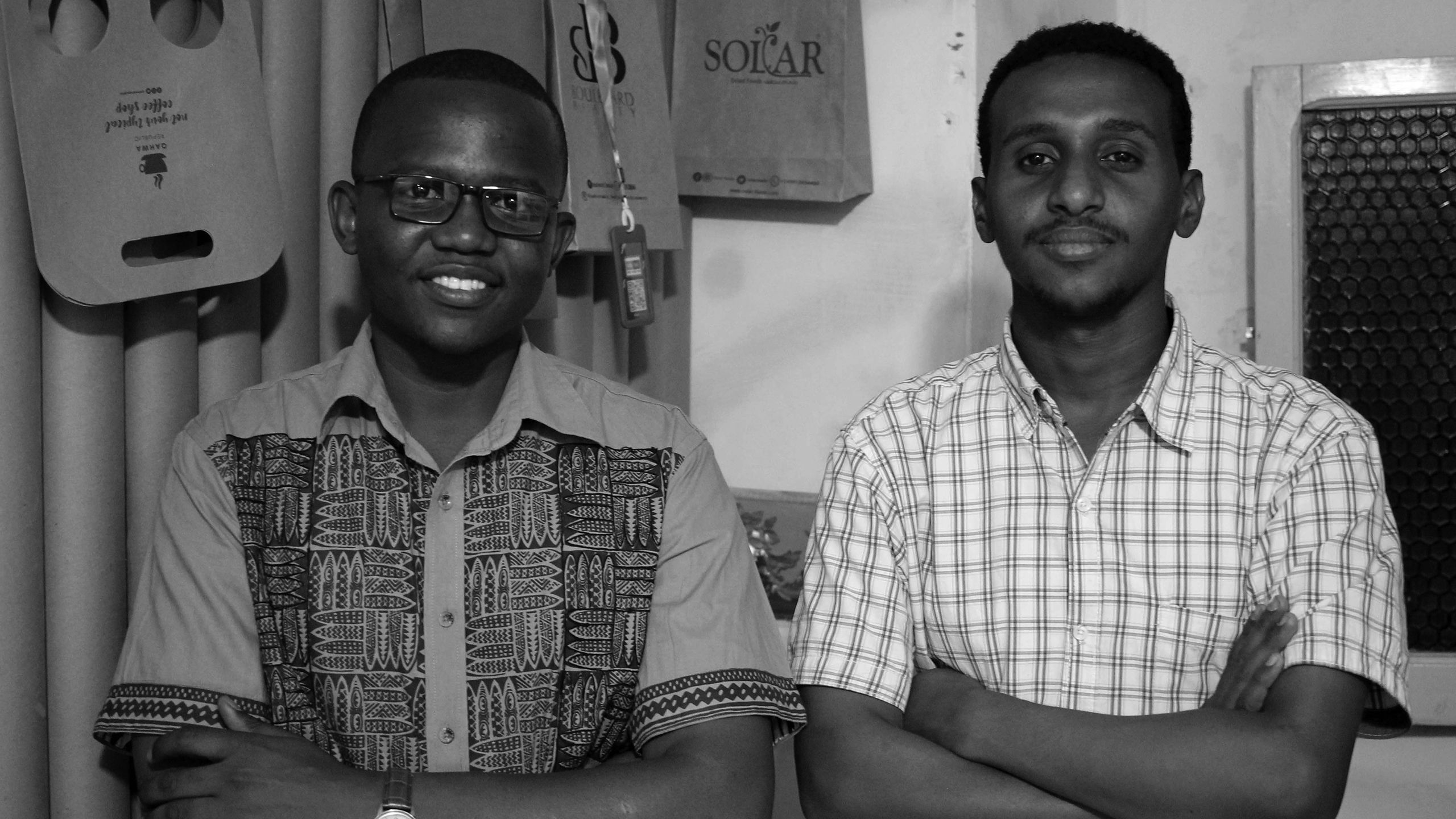

Mohamed Alrasheed and Moutaz Mohamed of Sudan Drums

Mohamed Alrasheed and Moutaz Mohamed of Sudan Drums

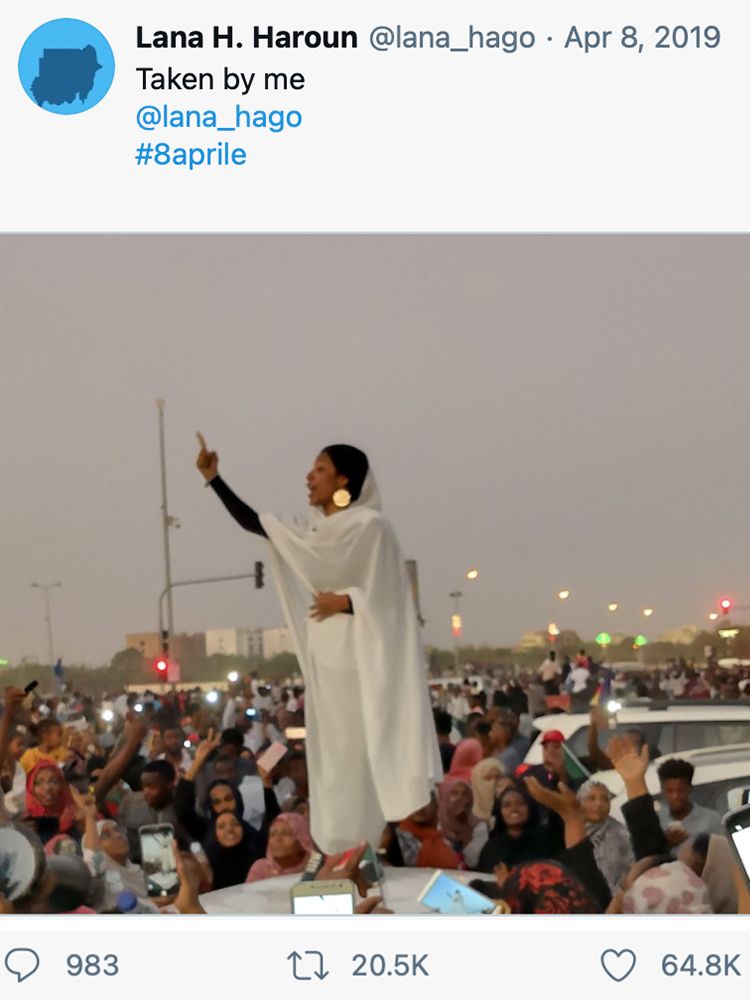

Alaa Salah, the revolution's kandaka, captured by Lana Haroun on Twitter

Alaa Salah, the revolution's kandaka, captured by Lana Haroun on Twitter

Anda’s story about the attack on the sit-in is shocking, but, for her, the violence is not what defined the revolution, it’s how Mellow’s community of artists and musicians contributed to the change.

“The revolution was sustained because of the arts in it,” she says. “Even the street children, the people with no political background, they were educated by the songs of the revolution.” This is why, to Anda, it’s important that Mellow continues as a successful enterprise, so that the spirit of the revolution can continue.

A few miles away, Rabah Hassan, a nursery school teacher, describes how joining percussion performance group Sudan Drums three years ago helped her to overcome her shyness. “I’m an introvert and it was a real challenge for me, but it’s improved my confidence and self-worth,” she says. Another member of the group, Moutaz, interrupts to give another example of how the arts – and Rabah – pushed forward the revolution. “This kandaka is very humble,” he says. “She was leading them at the sit-in – they were drumming on the bridge.”

A kandaka is a strong woman, meaning queen in the Nubian language, and it’s used often to refer approvingly to the women who took key roles in the revolution, leading chants and expressing their opinions through rhythm and music. A social media image that went viral during April 2019 shows a young woman called Alaa Salah, in a white robe, echoing a traditional Sudanese “toob”, with gold earrings, standing on top of a car, leading a call and response, demanding change – she is the ultimate kandaka of the 2019 protestors.

Sudan Drums

Sudan Drums was established in 2007 as a performance group as well as offering free drumming workshops. In 2019, the organisation turned itself into an enterprise by charging for its classes in djembe and dundun, investing the income back into buying new instruments and other equipment, its studio costs and transport.

Recognising the therapeutic value of drumming, the team also began to offer classes to young people with disabilities and special needs. When we visit, several participants endorse the healing power of the classes – one says that he has reduced the medications that he takes for his bipolar disorder and another describes how drumming helped her hands recover from surgery.

We’re capacity-builders for people

“All the negative energy goes when you drum,” says Mohammed Ahmed, who has responsibility for the enterprise’s finances. “I tell people to go there and play and feel good about yourself. That’s why I’m addicted – you come out and you feel good.”

“We're capacity-builders for people,” adds Mohamed Alrasheed, who deals with graphic design for the group.

The group began delivering classes again in October after lockdown, but the rising cost of public transport means that fewer people have been able to join in. Although the group still aims to grow, Rabah Hassan, who looks after the group’s communications, says they are having to explore other options too such as online classes and resources available. “We’re studying all the possible options we have to keep the beat alive,” she says.

We feel this positive energy all around Khartoum – and it’s not just among the people who are directly involved in music and culture. Qahwa Republic is a café selling coffee, tea and cakes, and it’s so busy on the Friday evening when we visit that we can hardly hear each other speak. Co-founder Samir Shulgami explains that during the sit-in this place was also a focal point for protestors to gather – they stayed open as much as they could as long as it was safe.

“During the revolution, we were part of the change,” says Samir. “We started seeing the new face of Sudan in our brand…this is the energy we took from the sit-in. What you see here is an extension of the sit-in.”

During the revolution, we were part of the change

These entrepreneurs all tell us they want to see a country whose culture and heritage are valued by the outside world, where people have the freedom to dress as they please, where musicians and artists can express themselves, and where stability and prosperity can finally find footholds.

Qahwa Republic is buzzing on a Friday evening

Qahwa Republic is buzzing on a Friday evening

Samir Shulgami: "We started seeing the new face of Sudan in our brand"

Samir Shulgami: "We started seeing the new face of Sudan in our brand"

Qahwa Republic

Qahwa Republic is where, co-founder Samir Shulgami, explains, he wants “coffee and dessert lovers” of all different ages and backgrounds to enjoy the “ultimate quality experience”.

This popular, western-style café is built on a detailed business plan and marketing strategy and also draws on the strengths of its sister marketing company, the complexities of which Samir attempts to explain above the din of dozens of people chatting on this busy Friday evening in Khartoum.

We rise by lifting others

While it may look like many other international coffee chains, Qahwa is founded on a social mission – to bring more young people into the catering industry and to employ those who may not have got a job elsewhere.

“Through our business we are trying to give as much as we can to these young people who want to work and can’t find an opportunity,” says Shulgami. “We believe that if they aren’t working, they are open to so many other risks.”

What’s more, Shulgami believes that this business, which he runs with co-founder Ismail Mirghani, is part of building “a new Sudan”. As he says: “We believe that we rise by lifting others.”

Sudan's social entrepreneurs took part in Social Enterprise Day's global #WhoKnew campaign in November 2020

Sudan's social entrepreneurs took part in Social Enterprise Day's global #WhoKnew campaign in November 2020

The research shows the "exciting potential" of this approach to business

The research shows the "exciting potential" of this approach to business

Until 2018, when the British Council began to support the development of social enterprises in Sudan as part of its Global Social Enterprise programme, the concept was almost unheard of. However, as in in many other countries, the term may be new, but the idea is not. For example, through Sudan’s traditional endowment (‘waqf’) system, properties or investments are placed into the custody of someone who administers them for the benefit of a particular cause, such as shelters for the poor, hospitals and education centres. Co-operatives have been legally recognised since the 1950s, and, going further back, people share expenses of events such as weddings or wakes through a ‘kashif’.

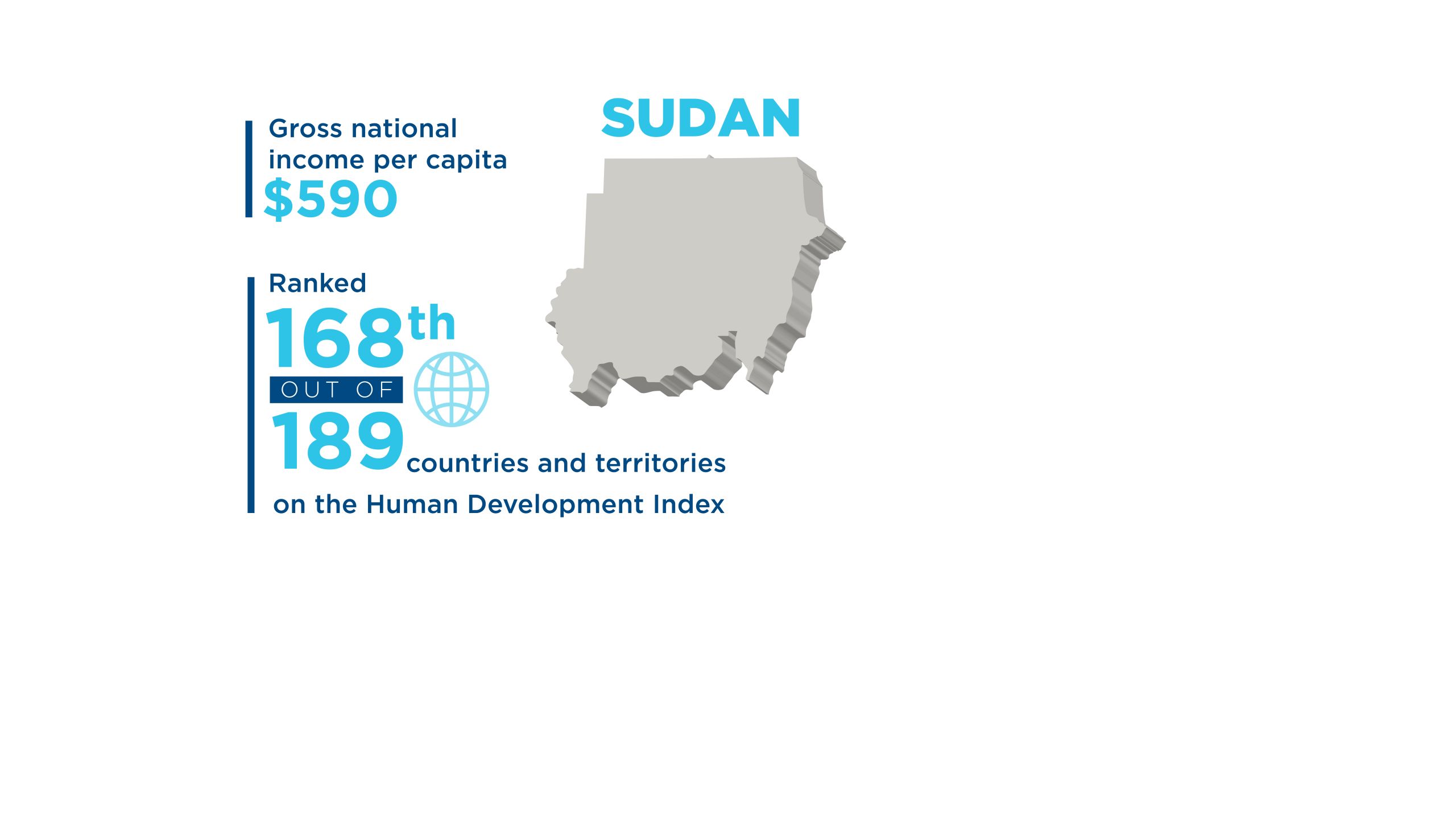

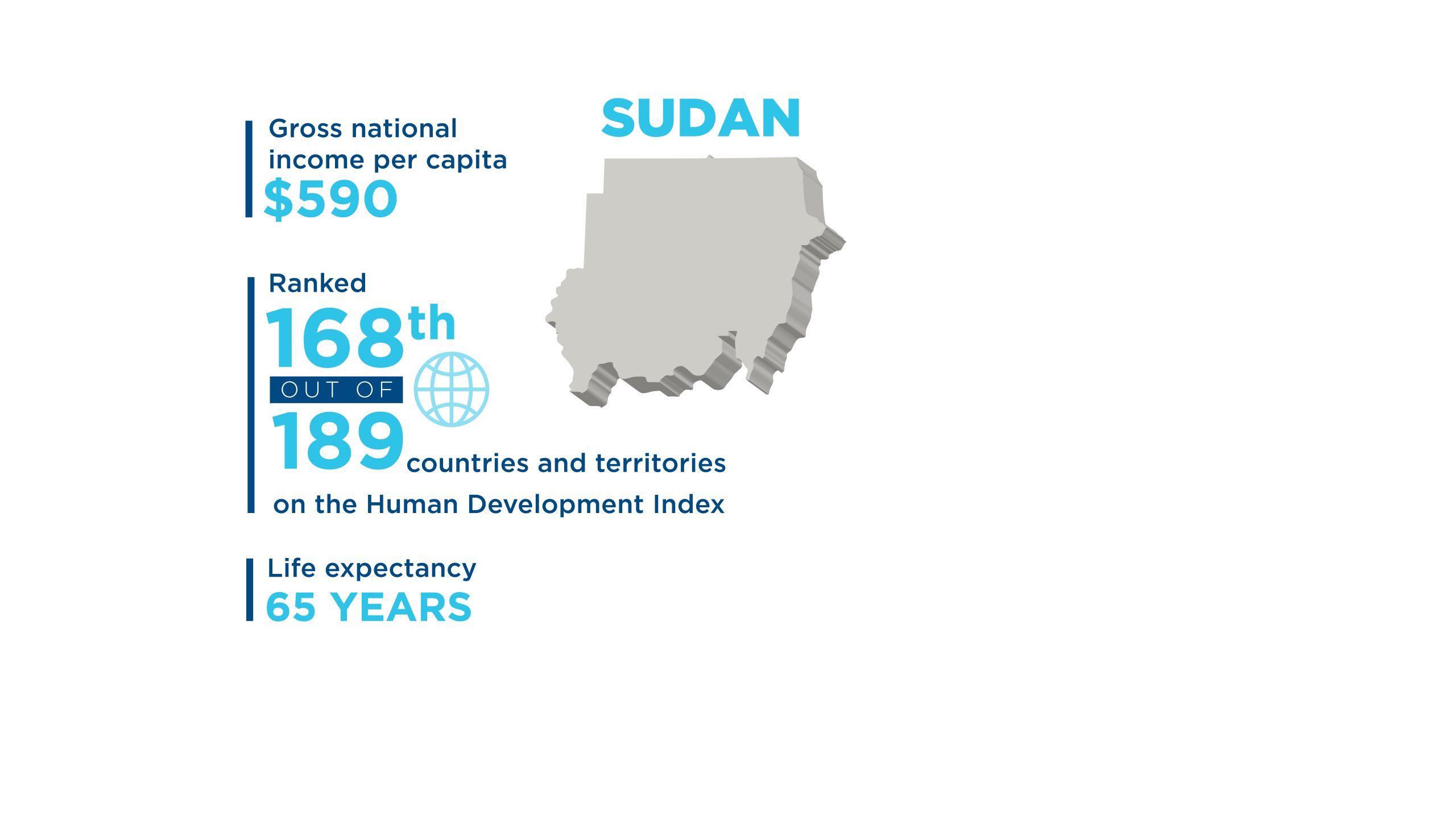

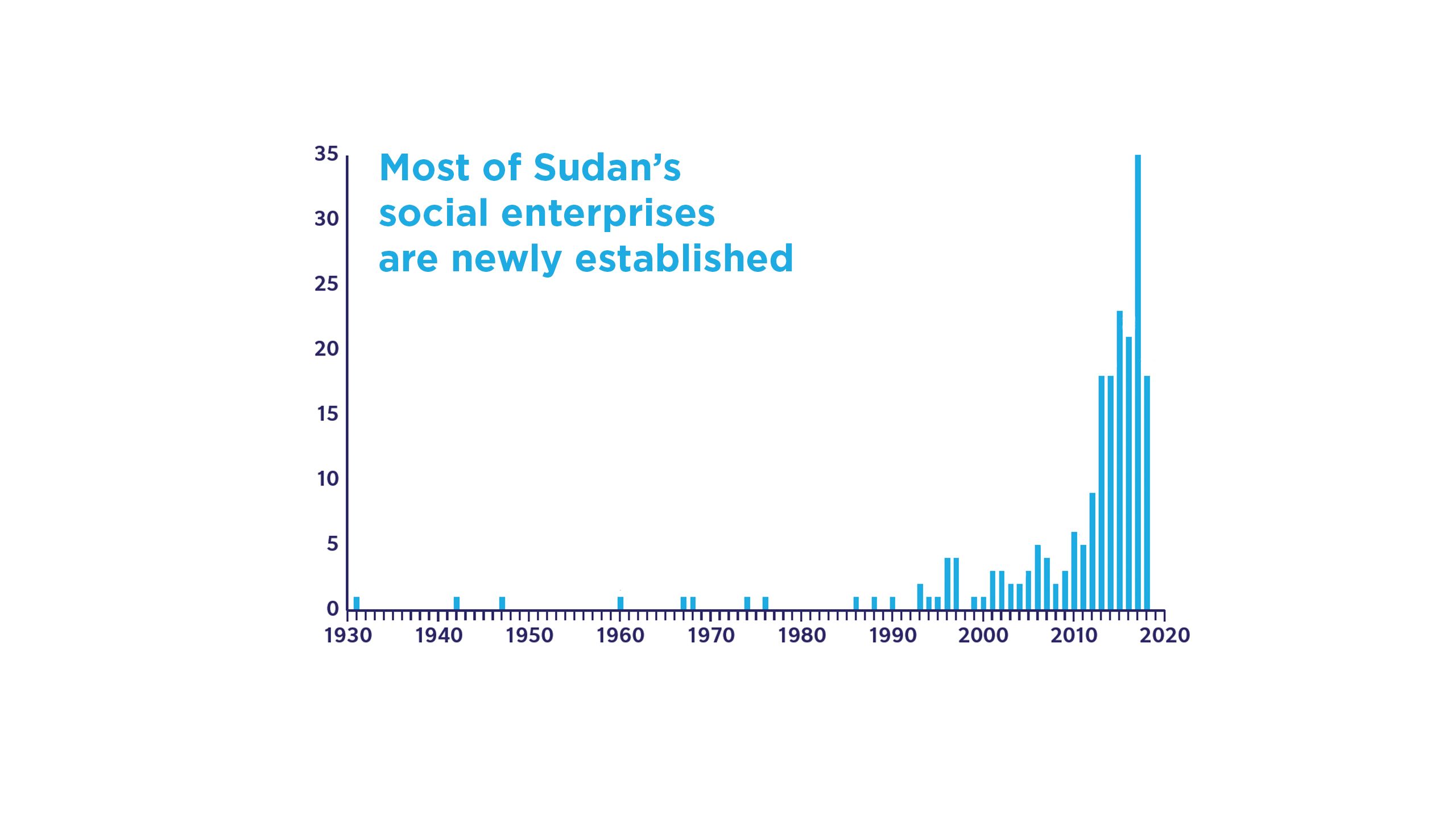

Part of the British Council’s social enterprise project was to carry out Sudan’s first social enterprise mapping exercise. Although the research was forced to a halt during the revolution, and then interrupted by the Covid-19 pandemic, The State of Social Enterprise in Sudan is finally complete and launches on 30 November 2020.

The researchers conclude that “visibility and public understanding of social enterprise is still limited”, but emphasise “the exciting potential of this approach to business in Sudan”. They also note that since the revolution, “people have started to work more collaboratively to create positive change, and entrepreneurs have attempted to scale up their work towards the ambition of a better Sudan”.

One of the most important outcomes of the research is a definition of social enterprise. For Sudan, the researchers concluded that social enterprise can be defined according to the following characteristics:

- Having a core mission to deliver support to achieve social and/or environmental benefits.

- Carrying out trading activities.

- Having an emphasis on reinvesting profits to deliver benefits to society and communities.

Based on a survey of 223 social enterprises, the researchers believe that there are around 55,000 social enterprises in Sudan. With no legal recognition, social enterprises take many different forms, including private companies, non-governmental organisations and associations, operating in many different sectors including health care, agriculture and the creative industries.

Most of the social enterprises surveyed are new: 65% were set up since 2013, and 67% of leaders are under 45 years old. Social enterprise leaders are also highly educated, with 84% having completed higher education or beyond. And 42% of leaders are women which, from the limited data available, seems to be a more favourable gender balance than the wider business environment.

The 223 social enterprises are providing 1,578 people with full-time jobs, 923 with part-time jobs and more than 3,000 with volunteering opportunities.

At the time of the research, the entrepreneurs surveyed were optimistic: 78% reported breaking even or making a surplus during the previous year, and 85% expected turnover to increase during the following year. The Covid-19 pandemic has probably thwarted many of those ambitions: from the anecdotal evidence Pioneers Post has been able to gather over the past weeks, many of the social enterprises were forced to close during the pandemic and are only now beginning to re-emerge and plan once again for their future.

The research shows that the single biggest barrier to growth for Sudanese social entrepreneurs is obtaining finance, and this is compounded by the unstable economic climate, lack of awareness and limited support from government.

Amro Makki, the British Council’s director of programmes and partnerships in Sudan, points out that positive steps forward are being made. One of the most important outcomes of the three-year social enterprise programme is the establishment of the Sudan Social Enterprise Association, which will take forward the support of the nascent sector. The association is headed by the charismatic Hatim Mubarak Hassan, an engineer who, with his friend Mohammed Elkhatim, created a drone to combat Sudan’s desertification and a social enterprise to push forward the project, and who, in 2018 won Sudan’s own Dragon’s Den-style TV programme, Mashrouy.

“The association is beginning to influence policymakers to help support the social enterprise ecosystem,” says Amro. He adds that Sudan’s minister for labour and social development, Lena el-Sheikh Mahjoub, has a proven interest in the area, having been involved in the Impact Hub in Khartoum and as a graduate of the British Council’s Active Citizens programme.

Rania Ramadan set up Asis and Zahra Gallery. Her green neighbourhood initiative encourages people to grow houseplants

Rania Ramadan set up Asis and Zahra Gallery. Her green neighbourhood initiative encourages people to grow houseplants

Hatim Mubarak Hassan of Sudan's new Social Enterprise Association

Hatim Mubarak Hassan of Sudan's new Social Enterprise Association

Mellow Art Space

Co-founder of Mellow Art Space, MJ, has a dream that the cultural hub in Khartoum will one day be “the biggest arts space in Africa”.

Since 2017, the Mellow team members have brought together photographers, musicians and artists in these small brightly painted interconnecting rooms above a shopping centre. Artworks line the walls, and in one tiny corner, speakers and instruments are piled up. They hold gigs with well-known bands, and open-mic nights, selling tickets to raise money, but, as there’s not a lot of room, lots of people tune in via social media broadcasts. They also earn money through offering music classes, film screenings and giving space to artists to display their work.

In the centre’s first few years it risked attracting the suspicion of the authorities with its young, alternative looking people going in and out; in pre-revolutionary Sudan, dreadlocks and tattoos were a statement of non-conformity. “In Sudan, whenever there is an apartment with girls and boys coming in and out, they think it’s a bad place for prostitution or drug dealing,” says co-manager Anda Kamal Yousif. That was the most worrying thing, she says, that they would be arrested for that.

During the revolution, the centre became a refuge for some of the protestors and this sense of community continues today. Mellow reopened recently after the lockdown, which began in April and lasted until September, and is keen for the arts to once again play a key role in taking Sudan forward. Its aim, it says, is for “young artists, musicians and designers to learn, gather, collaborate, share experiences and exchange ideas”.

Mubarak Musa: "Our liabilities are eating us alive"

Mubarak Musa: "Our liabilities are eating us alive"

Global economic turbulence has put Enas Elfatih's recycled textiles enterprise plans on hold for now

Global economic turbulence has put Enas Elfatih's recycled textiles enterprise plans on hold for now

Eight months on from our visit in March, people tell us that the post-revolutionary mood of optimism is beginning to evaporate. The second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic is hitting hard, the country has been hit by devastating floods and, since November, a growing wave of refugees is arriving fleeing unrest in Ethiopia.

Political infighting is destroying the unity of the new government. The first democratic election keeps getting postponed and is now not expected until 2024. The economy is shattered; inflation, at the latest count, was at 270%. In Khartoum, it can take two or three days to queue for fuel, making it impossible for people to get to work; public transport and taxis are too expensive for most. Bread queues last for hours and there are an estimated 9.6m people who are ‘severely food insecure’, says the UN.

Yet Sudan’s social entrepreneurs remain committed to their goals. In a flurry of messages before we publish this feature, the entrepreneurs we met in March send updates on how the pandemic has affected them and what they are planning to do in the near future. Some sound downhearted, knowing they have many more hurdles to overcome than they originally anticipated. As one points out, the lack of government support is becoming ever-more frustrating. “There is no clear vision by the government and no kind of support…no business can plan anything in such a political and economic climate,” she writes.

Mubarak Musa and Mustafa Altijani set up Green Space in West Darfur to support entrepreneurship among the local young people through providing shared office space and training. The ultimate aim is to reduce violence and criminality in this conflict-prone area.

“People think there’s a dream land elsewhere, but they’re forgetting that people can create a better life in their own communities,” Mubarak told us in March.

But in an email update this month, Mubarak says that the pandemic was a “big blow”, forcing the business to close temporarily. “Our liabilities are eating us alive,” he adds. Green Space is attempting to pivot to virtual activities, but it’s tough in the face of political and economic instability along with an unreliable electricity supply and internet service.

Textile graduate Enas Elfatih’s tells us her plans are on hold for now. Earlier this year, she had completed market research and product testing to make clothes and bags out of the offcuts which would usually be thrown away from fabric factories.

She was ready to register her business and establish a workshop, but the global economic turbulence meant that acquiring the sewing machines and materials was impossible, while the lockdown meant that she couldn’t gather together her team. Now she’s continuing with her preparations, hoping to get up and running after the pandemic.

Others, however, like Fanda Pack, have done a pandemic pivot, adapting what they were doing and trying to keep going.

Fanda Pack

In March, we called into the tiny office of Fanda Pack, run by computer science graduate Fares Suliman and electronic engineering graduate Aamer Mahmad.

At the time, the two young entrepreneurs were riding high on their first successes of their eco-friendly paper packaging enterprise which launched in October 2019 – they’d conceived it during the revolution, and started up as soon as they could afterwards. Not only do they have an environmental mission, but they also offer flexible jobs to students who can find it difficult to support themselves during their studies.

Fanda Pack’s ambitions, they said, were to be the “leading eco-friendly packaging company here in Africa”, noting opportunities in Rwanda and Kenya where, like in Sudan, plastic bags are banned, but there are as yet no good, cheap substitutes.

The pandemic forced them shut their premises and cease trading, but they’ve bounced back, they tell us, reopening in August with adjustments to allow their staff to be socially distanced in their cramped workspace. They have also had to change sales prices because of inflation and they’ve shifted to selling online with an e-payment service.

Their optimism remains undimmed though. “We’ve been through a lot since 2018,” they write in an email. “We hope for a bright future ahead for Sudan.”

“Social enterprise still has a long way to go in Sudan,” says the British Council’s Amro. “We’ve climbed the mountain 60%, and that last 40% is going to be hard. But when we do it, it will make a huge change.”

Whatever happens in the coming months and years, it’s clear that those in charge of this unstable nation shouldn’t lose the support of the young entrepreneurs that we met.

“The youth here is everything,” says Rabah of Sudan Drums. “We are powerful. We are the weapons.”

Pioneers Post editors Anna Patton and Julie Pybus visited Sudan in March 2020 to provide training to social entrepreneurs and journalists as part of the British Council’s Social Enterprise Programme.

Header image: A girl from the nomadic Umbararo tribe in Sudan's Blue Nile State. As they come of age, girls are garlanded with copper jewellery. Photo by social enterprise Art Lab which celebrates Sudanese culture through photography. Section break images: Tuti Bridge, Khartoum, at the confluence of the White Nile and the Blue Nile by Anna Patton; The view west along the Blue Nile from the Corinthian Hotel on Nile Street; Graffiti in Khartoum by Anna Patton. Other images: Social enterprises and entrepreneurs in Khartoum by Anna Patton; Pioneers Post training by Darkroom Productions; Revolution by Mamadou Abozeid/Grotesqu9; Omar al-Bashir reproduced under a Creative Commons licence from Paul Kagame; Abdalla Hamdok reproduced under a Creative Commons licence from Ola A Alsheikh.

Additional reporting by Anna Patton. Design by Fanny Blanquier.

This immersive feature was produced by Pioneers Post, the leading global news platform for mission-driven businesses, social entrepreneurs and impact investors. We’re also a social enterprise ourselves, with profits ploughed back to support our community of positive changemakers: you can support our work by subscribing, from just £4 per month (and further discounts for start-ups and students).

Get in touch if you'd like to work with us to tell your story.