The people racing to replant Africa

It’s one of the most ambitious environmental projects ever planned – but even with millions of people’s livelihoods at stake, it’s quite possible that the Great Green Wall of Africa won’t meet its jaw-dropping targets. Unless, some argue, plans to reforest an 8,000km cross-continental stretch can be pulled from the corridors of power and driven by local citizens. In the Gambia, one of Africa’s smallest countries, that’s starting to happen – but the clock is ticking.

“Seven years ago, we never bought rice from China. Today, my parents have to depend on my paycheck to buy bags of rice to supplement the little rice that we can grow here.”

Kemo Fatty comes from a family of farmers living on the north bank of the Gambia river. For generations, they had grown everything they needed on the region’s fertile floodplains. But in recent years, climate change and deforestation have made the region nearly uncultivable. As there isn’t enough rainwater washing down the river, saltwater from the sea moves upstream and destroys crops. And because of the lack of trees, the soil has lost all its nutrients, and crops don’t grow.

Like everywhere in the Sahel – the 3 million sq km region between the Sahara desert and the African rainforest – the Gambia is on the frontline of climate change. “It’s a race against water,” says Fatty. “Water is the real commodity here. We are losing more and more water, which is making people poorer and poorer.”

Over the past few decades, the Sahel’s natural resources have dwindled, leading to a loss of biodiversity, poverty, mass emigration, violence and food insecurity, in a region where most people rely on agriculture for subsistence – 60% live in rural areas.

Temperatures in the Sahel are expected to rise 1.5 times faster than in the rest of the world, and could reach up to five degrees celsius above pre-industrial times. That would make the region uninhabitable. Yet the Gambia is only responsible for 0.05% of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, according to a UN FCCC paper published in 2016.

“It has become personal now, because we see first-hand that we are a helpless nation,” says Fatty. His own brother is among the many young people who have left the country to seek better opportunities in Europe, hoping to be able to help their families from abroad. “These are not economic migrants, they are climate migrants. Because the climate is affecting the economic power of our state.”

Fatty stayed. Just 28 years old, he is now the executive director of Green Up Gambia, an NGO helping rural communities mitigate and adapt to climate change, and has recently joined Civic, a UK-based social enterprise working to drive positive change around the world, as head of community engagement. With both organisations, he’s working on a mammoth project: Africa’s Great Green Wall.

Read more stories of entrepreneurs helping to restore the planet in Pioneers Post's Earth Fixers series

A woman in Mauritania tends to crops threatened by drought. Photo by Pablo Tosco/Intermon Oxfam, Valérie Batselaere

A woman in Mauritania tends to crops threatened by drought. Photo by Pablo Tosco/Intermon Oxfam, Valérie Batselaere

Climate activist Kemo Fatty's village in northern Gambia has been strongly affected by climate change

Climate activist Kemo Fatty's village in northern Gambia has been strongly affected by climate change

MORE THAN A FOREST

“The Sahel is the crucible of the biggest threats facing all of humanity today,” says Alexander Asen, creative director at Civic, who recently produced a documentary on the project. Like Fatty, he sees a possible solution to those problems in the Great Green Wall, and previously led a campaign promoting it at the UN Convention to Combat Desertification.

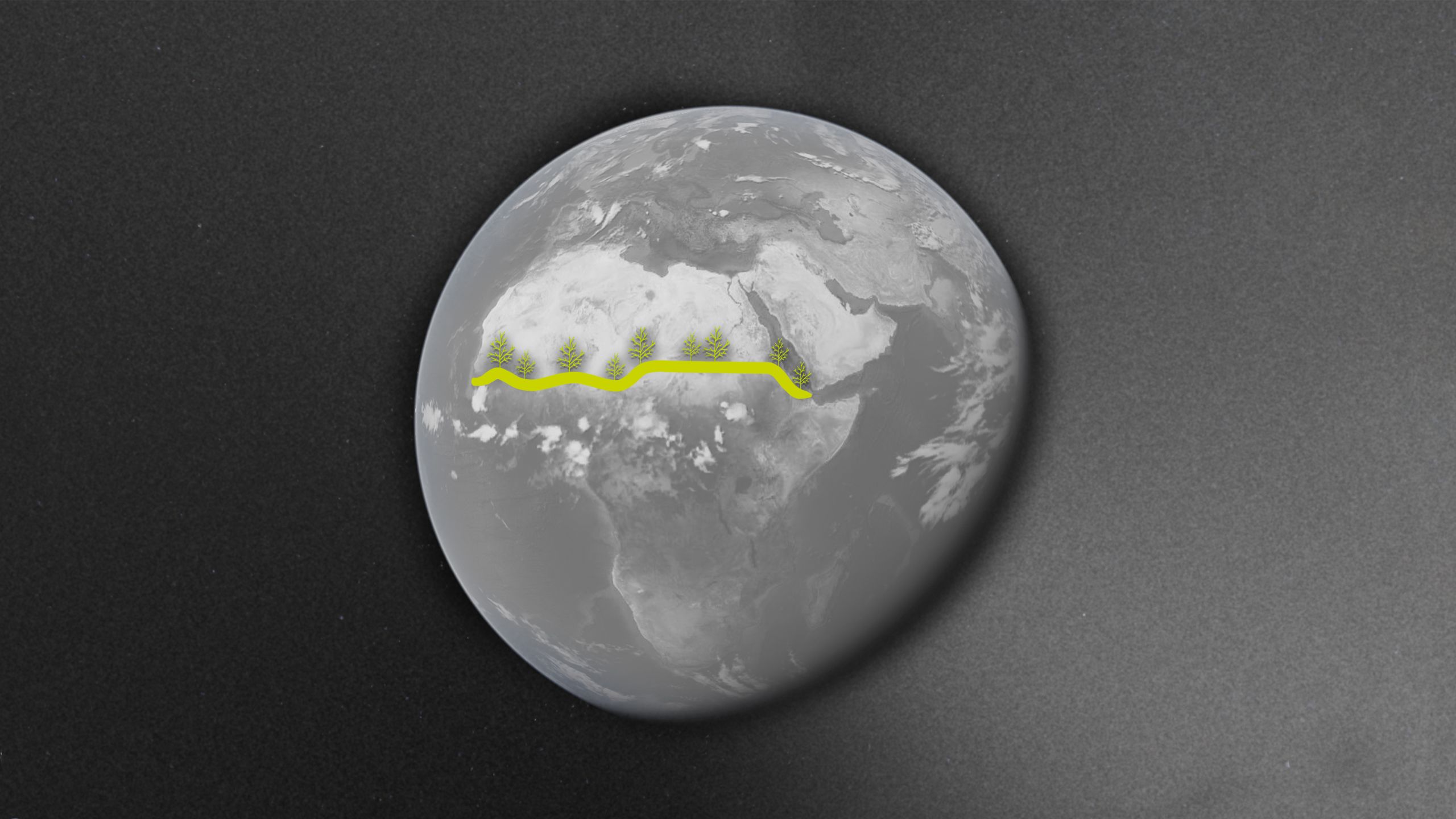

The Great Green Wall is an African-led initiative that aims to build an 8,000km barrier of plants and trees at the southern border of the Sahara desert, from Senegal in the west, to Djibouti in the east, in the hope of rebuilding what used to be a lush and fertile region. The idea emerged in the 1980s, as climate change, unsustainable agricultural practices and population growth started depleting natural resources and visibly increased desertification. The project eventually launched in 2007, with the support of the African Union.

Almost 15 years later, progress has been slower than expected, with only about 18% of the wall planted. But the idea of a simple barrier of trees across Africa has evolved into something bigger: regenerating a whole region. The Great Green Wall is now a mosaic of local initiatives which, beyond rebuilding natural woodlands, are providing food through climate-smart agriculture, creating green jobs, supporting women to become more independent and rebuilding the economy for the younger generation.

So far, 18m hectares of degraded land has been restored and 350,000 jobs have been created across the Sahel. If the Great Green Wall achieves its objectives, by 2030, 100m hectares of land will have been restored, 250m tonnes of carbon captured, and 10m jobs created. But it will cost between $36bn and $43bn, on top of what’s been spent already.

The project is funded by the member states of the African Union and international partners, including the World Bank and the European Investment Bank, who together in January 2021 committed $14bn to the 'Great Green Wall Accelerator'. This money will direct funding to local organisations, and help them coordinate and monitor their work.

Tree planting regenerates the soil and enables local people to grow vegetables

Tree planting regenerates the soil and enables local people to grow vegetables

A man plants a tree seedling as part of a regeneration project in northern Senegal

A man plants a tree seedling as part of a regeneration project in northern Senegal

THE ULTIMATE GUARDIANS: THE LOCAL COMMUNITY

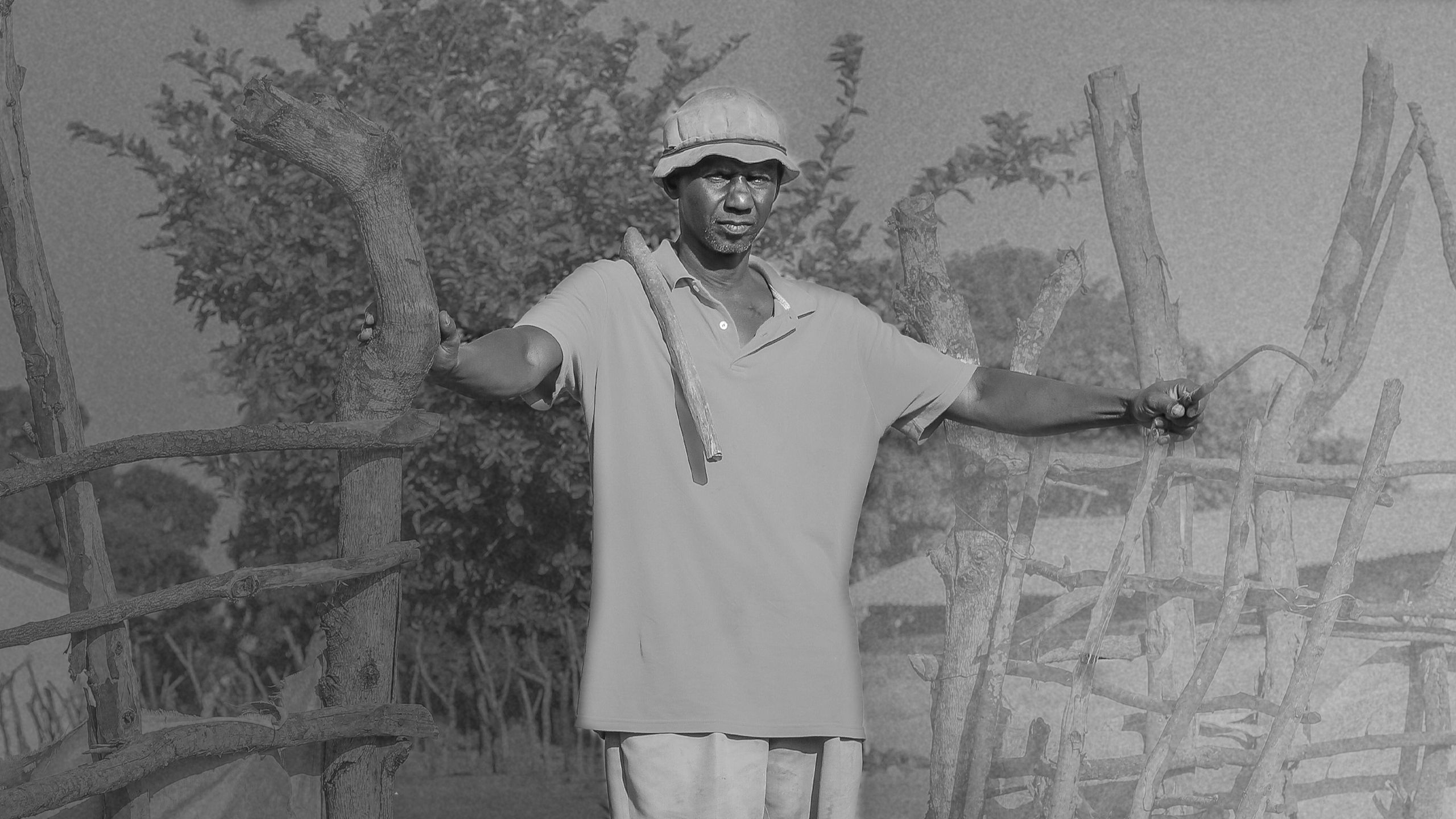

There is a discrepancy between this growing political momentum in the corridors of power, and the awareness of the project in the regions affected. Efforts to engage local populations are needed, says Asen. “People on the frontlines often have no idea this movement is happening, we need far deeper awareness and incentives”. The Great Green Wall can only succeed, he says, if local people – the “ultimate guardians” of the project – adopt it as their own.

“On one hand, there are financial challenges, and on the other, there are challenges around community engagement,” Asen says.

In the Gambia, Civic is spearheading a new pilot programme, the Great Green Wall Frontline, in partnership with the African Union. The programme aims to encourage local people to help shape the future of the Gambia’s section of the Great Green Wall, through citizens’ assemblies. Fatty hopes to reach everyone across the northern bank of the Gambia river, starting with a “leadership briefing” that will involve all local leaders: head of districts, village heads and village development committees as well as traditional communicators, spiritual leaders and the elders.

“All of these structures in the village need to understand what it is that the Great Green Wall entails and how we are going to deliver it,” says Fatty.

A lot of environmental initiatives have come and gone in the region, he explains, “but we are yet to see a visible, tangible impact of these projects.” There needs to be “this cross-cutting dialogue, this intergenerational dialogue to really understand what has not been going well… What did we do wrong? How can we do it right?”

Rather than imposing decisions from the top down, Fatty says, the project needs to either reform or build on existing systems.

“The power must be put in the hands of the local people who are on the ground,” he says – not in the hands of the international NGOs who come and go again with no lasting impact.

Community members should be involved in the main effort of tree planting, but they also need to understand that their behaviour needs to change, that they need to stop practices such as cutting down trees to create farming space or engaging in timber trade.

The citizens’ assemblies will create a pilot model and a DIY toolkit that can be used by other activists across the country. Ultimately, a national assembly will present the government with feedback from local people that can feed into policies on land use, tree-planting incentives and so on. “We want the issues of climate change and land degradation to be mainstreamed across every sector of planning and development,” says Fatty. He hopes other countries will follow.

“My brothers are jumping into the boat across the Mediterranean, because they feel like the pasture here is no longer green... to restore our pasture to make our place green, we need to revive the power of the soils.

“And this can only be done when there is a clear understanding, when there's a citizen-powered movement that can drive the change of delivering 12.5m trees on the soil in the Gambia, restoring hectares of degraded land across every community.”

Trees need to be planted during the rainy season, which only lasts three months in the Gambia

Trees need to be planted during the rainy season, which only lasts three months in the Gambia

Aji Sainabou Panneh, a member of the community taking part in the Great Green Wall effort in the Gambia

Aji Sainabou Panneh, a member of the community taking part in the Great Green Wall effort in the Gambia

Local resident Almamy K Fatty. The power must be put in the hands of the local people, says Kemo Fatty, not international NGOs who come and go

Local resident Almamy K Fatty. The power must be put in the hands of the local people, says Kemo Fatty, not international NGOs that come and go

How to build a green wall

Trees need to be planted during the rainy season, which only lasts three months in the Gambia – down from six, because of climate change. Throughout the dry season, tree seedlings are grown in propagation centres – where they are kept in ‘nurseries’ and watered regularly. When the rainfall begins, they must be planted out quickly so that they can become mature and drought-resistant by the time the dry season starts.

With sufficient resources and planning, the Gambia stretch of the project could be completed in as little as five years. Many assume it takes decades to grow trees, but Fatty knows that’s not the case: his father built a “live fence” about seven years ago by planting trees rather than using expensive barbed-wire fencing. The cashew trees are now fully grown, protect the land and provide Kemo's father with an income from selling nuts.

In certain areas, the focus is on using planting as a means of income generation, Fatty explains, getting “money back into the hands of the farmers and the young people”.

Tried-and-tested solutions exist to do this. Creating interlocking systems where vegetables can be planted between the trees provides nutritious food to the local populations. Growing staple crops, such as cashews, rather than cash crops (those planted for export), supplies the local population with foodstuffs at a lower cost. Providing storage facilities means vegetables don’t go to waste. And engaging younger generations, for example by using school gardens as propagation centres to grow tree seedlings, gives children hands-on environmental education.

Many ways to help

For the past few months, international law firm Hogan Lovells has been working with Fatty, Asen and others at Civic on their Gambia project, to help them set up the right corporate structure and legal entity for it.

“I was blown away by how amazing an idea it is,” says Neil Mirchandani, partner at Hogan Lovells. “The idea of greening the Sahel... We thought this is something we want to support as best we can... There is almost no downside to it.”

Hogan Lovells has worked in Africa for more than three decades. It has built a network of law firms across the continent, the “Go Far Together” initiative, with a view to empowering local lawyers and their practices.

Beyond sharing expertise, Hogan Lovells has been building deep connections, offering secondments, seminars and partnership opportunities to local practices on social impact projects, such as the Great Green Wall.

As a $2bn international law firm, Hogan Lovells is also using its global network of contacts to support the Great Green Wall. The firm also seeks to raise awareness of the initiative among its clients, which may be keen to offer logistical or financial support.

“ESG issues are very big issues for many of Hogan Lovells’s clients,” says Mirchandani. “The environmental side of this is something we can excite people with.” And it’s not only about money: expertise in a relevant field or equipment can make a huge difference.

Hogan Lovells engaged with Gambian lawyers to advise on the local Great Green Wall project. Sourcing support locally brings business to Gambian law firms and brings the project closer to the community.

While a top-down approach is needed – international funding, expertise and so on – initiatives need to be supported and coordinated on ground level. “You need both of those together, you can’t have one without the other,” says Gill McGreevy, partner at Hogan Lovells.

Bringing communities on side is a “huge task” says Mirchandani. “You think the ground side of things is a given. We are asking people to change their way of life for what we think is a better, easier way of life. But we do have to make sure they are convinced.”

A SPIRITUAL CHANGE

If local solutions are scaled up, the Great Green Wall could dramatically improve biodiversity, and reduce poverty, mass emigration, violence and food insecurity in the Sahel – all of which would have positive knock-on effects for other parts of the world by helping tackle climate change and mass migration.

But huge challenges remain. Even after world leaders committed $14bn in January, African Union president Moussa Faki Mahamat reminded them that the investments made until now had been much lower than sums committed – and were often characterised by a certain “cacophony”, he said.

While international partners had shown enthusiasm for the initiative when it launched, 14 years later the “dream has somewhat faded”, he added. While the Sahel was fighting against terrorism, political crises and conflicts, malnutrition, Covid-19 and other pandemics, it would be a “fatal mistake” to let climate degradation increase in the region.

Even if local people become aware of the problem, conflict and poverty mean they must do whatever they can to feed their family. “People understand the problem, but they are helpless. So they will chop down the last tree, in order to survive,” says Fatty.

While timber trade is banned, millions of dollars worth of wood still leave the Gambia each year. The system is rife with corruption: $50 is enough to make a border guard avert his eyes when a truck full of logs passes by. Fatty, who used to work for the municipal council, explains that low wages make people more vulnerable to bribery. “When the police are not getting paid, they find it hard to serve and protect.”

There needs to be a “spiritual” change, Fatty says: “To save the world, we need to get inside the problems of greed, ego and convenience.” People in the Gambia used to be “as one with nature”, he explains. Many ancient customs were rooted in the idea that one mustn’t exploit the earth. He mentions the role of the Kankuran – a traditional spirit – who used to threaten villagers if they picked unripe fruit from the forest. Ancient laws used to safeguard natural resources; but colonisation and Western influence led Gambians to lose their sense of purpose, Fatty says.

He thinks the citizens’ assemblies can help reconnect people with these values, and give them the power to take action at the same time.

“The solutions are already on the ground, it's a matter of how we scale this up… I think there's a lot of things that can be done for us to really get the productivity of our land back. It's just a matter of putting the right people at the wheel. And of course, providing them with the right help and the right tools that they need.

“We are building hope, once more, something we never really have. We have lived with frustration for far too long,” says Fatty. The Great Green Wall was designed “in the corridors of the African Union”, but has never been rolled out to people on the frontline, he adds – until now.

“We need to get people on the frontline to restore land. This, I think, is the only hope for our continent.”

Top picture by Simon Townsley

All other photos courtesy of Great Green Wall

Design by Fanny Blanquier

Amadou Bah, a member of the community taking part in the Great Green Wall effort in the Gambia

Amadou Bah, a member of the community taking part in the Great Green Wall effort in the Gambia

Once fully grown, the trees provide local people with nutritious fresh fruit

Once fully grown, the trees provide local people with nutritious fresh fruit

This immersive feature was produced by Pioneers Post in partnership with Hogan Lovells and HL BaSE, the firm’s impact economy practice.

Get in touch if you'd like to tell your story.

J O I N T H E I M P A C T P I O N E E R S

SUPPORT OUR IMPACT JOURNALISM

As a social enterprise ourselves, we’re committed to supporting you with independent, honest and insightful journalism – through good times and bad.

But quality journalism doesn’t come for free – so we need your support!

By becoming a fully paid-up Pioneers Post subscriber, you will help our mission to connect and sustain a growing global network of impact pioneers, on a mission to change the world for good. You will also gain access to our ‘Pioneers Post Impact Library’ – with hundreds of stories, videos and podcasts sharing insights from leading investors, entrepreneurs, philanthropists, innovators and policymakers in the impact space.