Hope on the highway: how Riversimple is rethinking cars – and profits

For more than 20 years, Hugo Spowers has been developing a highly efficient, zero-emission car. It’s not only about the technology: he also wants to create new circular business models, while his unusual company structure ensures the environment and community are just as valued as its investors. But is Riversimple – at last – ready to hit the road?

Hugo Spowers is an unreasonable man. According to the London Business School, that is, which presented the entrepreneur with their ‘Unreasonable Person’ award in 2019 – praising his “enormous tenacity and stubbornness in pursuing an idea despite the difficulties encountered along the way”.

Spowers has shown two decades of tenacity as the founder of Riversimple, a company based in a small town in mid-Wales that makes hydrogen fuel cell-powered cars. While their only direct emission is water, hydrogen cars haven’t yet taken off as a low-carbon option for personal transport; too expensive, too difficult to make, not yet viable for businesses or consumers.

Riversimple proposes a solution that it says will make hydrogen cars work for everyone. After more than 20 years, it still hasn’t gone to market – but is the time ripe for a breakthrough?

* * *

Motorsport engineer Spowers came across hydrogen fuel cell technology and its application on cars while studying for an MBA in the late 1990s. Having spent nearly 15 years designing racing cars – a career he left for environmental reasons – he immediately saw the potential of hydrogen fuel cell-powered cars.

But to make it work in the real world, it required building a car “in a different way, with a different pattern of relationships,” he says. What was needed wasn’t better fuel cells or better electric motors, but a better architecture, both of the car – to make it more efficient – and of the way the car industry operates. The technology was there; the barriers were people, politics and inertia, Spowers says.

He designed the blueprint of what was to become Riversimple in 1999 based on the core elements of a super-efficient vehicle and a business model where transportation is sold as service, not a product. A few years later, he added a third element: the principles of a purpose-led, stakeholder-governed business. Combined, these would deliver a clear mission: “To pursue, systematically, the elimination of the environmental impact of personal transport.”

Now managing director of the company, Spowers explains that having those three pillars in place from the start was essential. The engineer believes this “whole business design” approach is not something that can be retrofitted onto an existing company: he gives the example of car manufacturers that are trying to incorporate hydrogen vehicle manufacturing into their existing manufacturing model, built for petrol cars, ending up spending billions to design a car when Riversimple does the same with a few millions. “They spend their time trying to solve problems of their own making,” Spowers says.

The engineer says he is “not impressed by the concept of pivoting, which is terribly fashionable. Because pivoting basically means you haven't thought it through properly in the first place.”

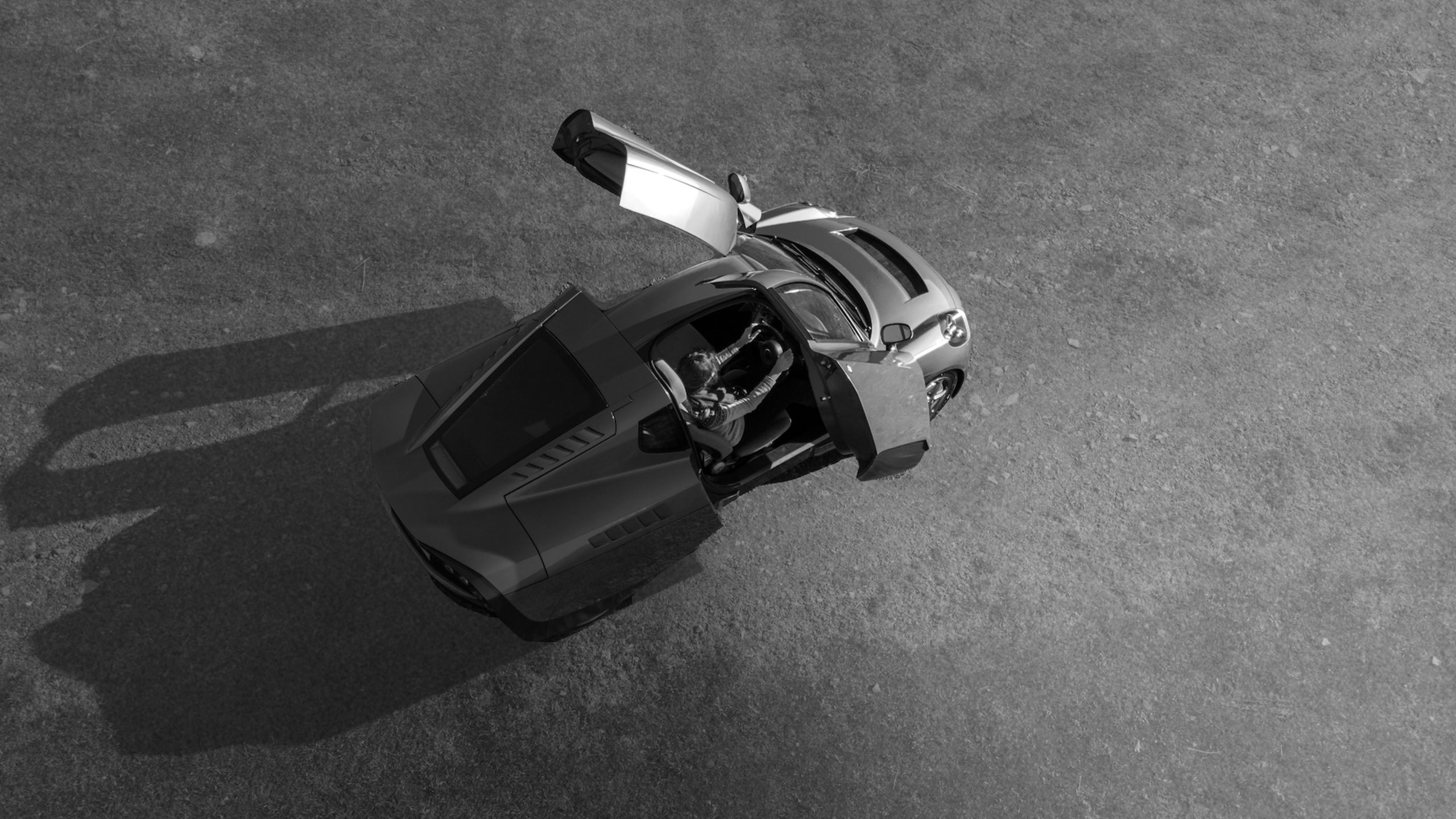

Over the years, Riversimple refined its corporate structure and got its first investment in 2007 – a “substantial amount” from a private family. The company now numbers around 25 employees and has raised a total of £24m in investment and grants. After a few prototypes, Riversimple’s first road-approved car, the Rasa (a two-seater named after “tabula rasa” – clean slate) launched in 2016. The car is not yet available for customers, and the company still doesn’t have any income; but Spowers hopes to bring a production car based on the Rasa to market in the next three years.

Hugo Spowers set up Riversimple more than 20 years ago with the goal of making hydrogen cars work for all.

Hugo Spowers set up Riversimple more than 20 years ago with the goal of making hydrogen cars work for all.

Spowers pictured in 2008. A former racing car designer, he began exploring hydrogen fuel cell technology from the late 1990s.

Spowers pictured in 2008. A former racing car designer, he began exploring hydrogen fuel cell technology from the late 1990s.

Light, efficient, green

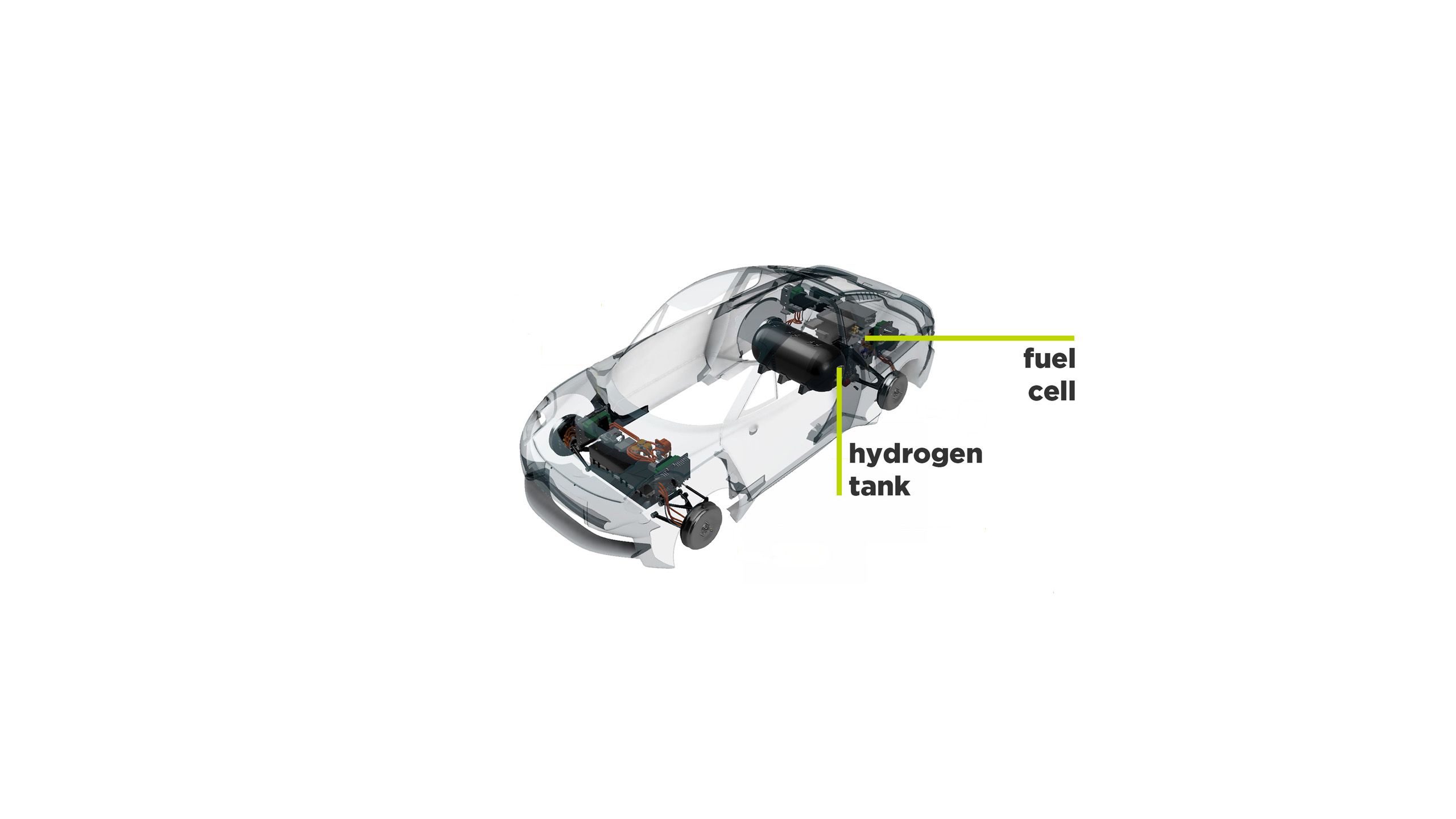

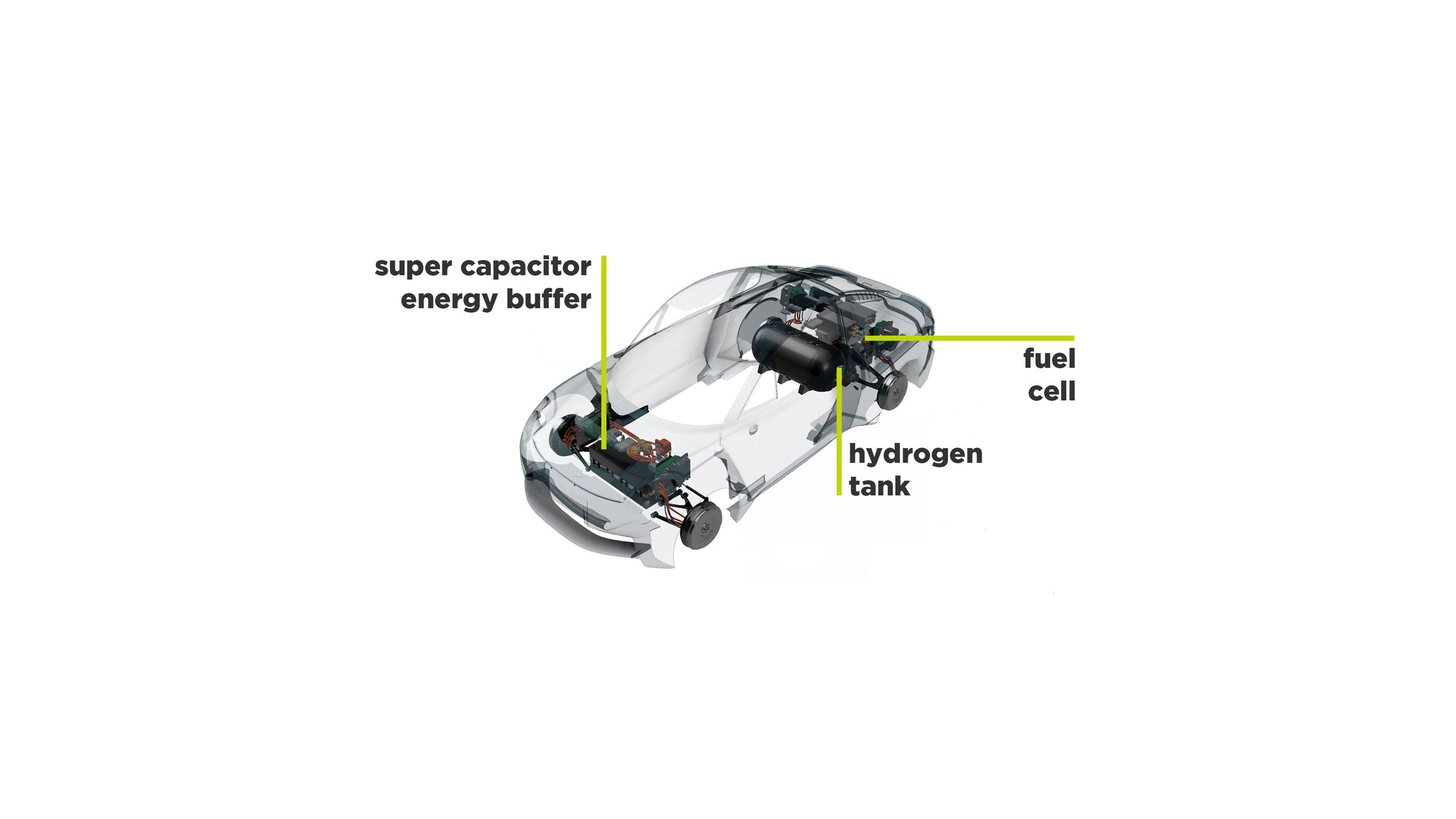

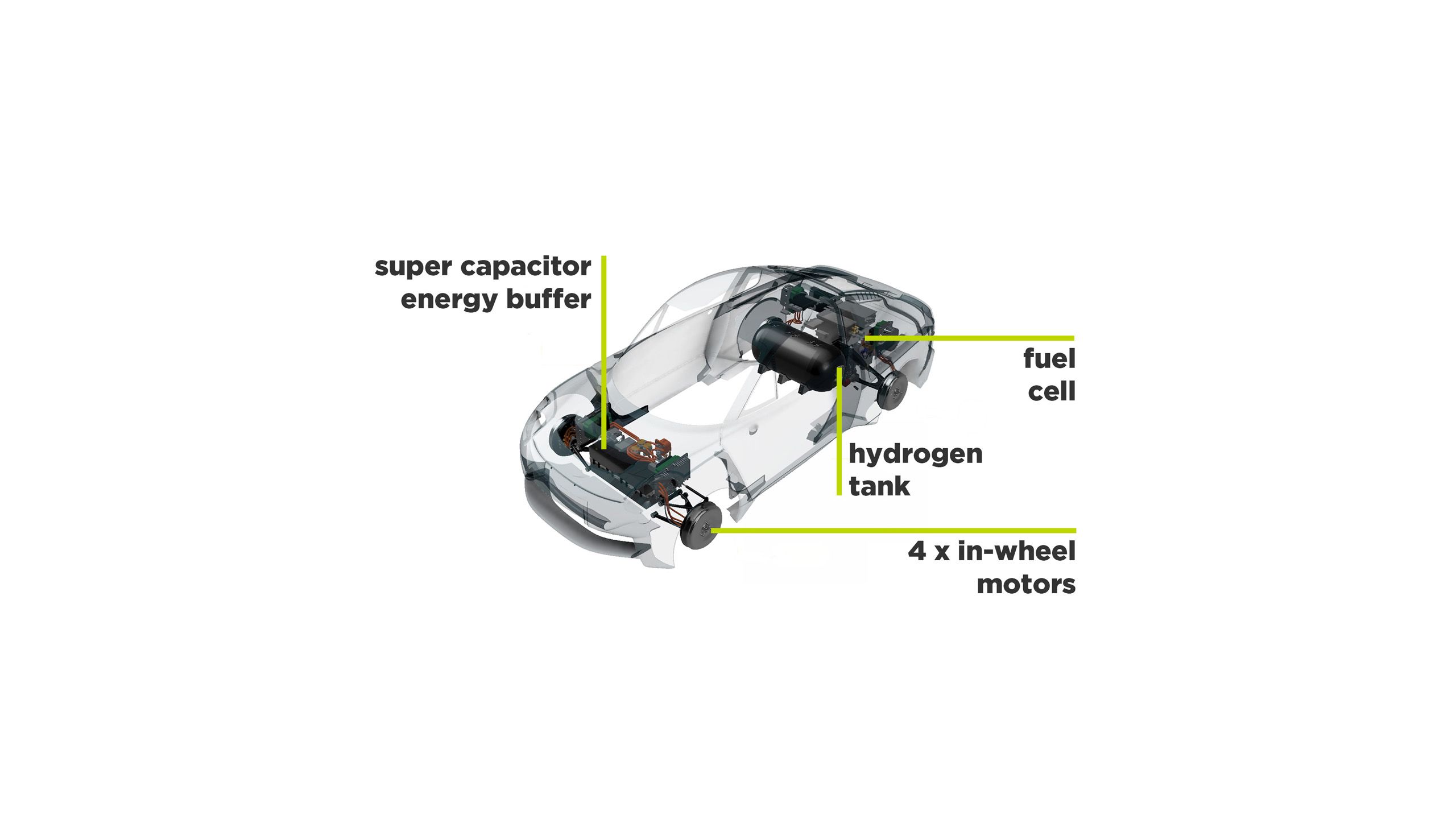

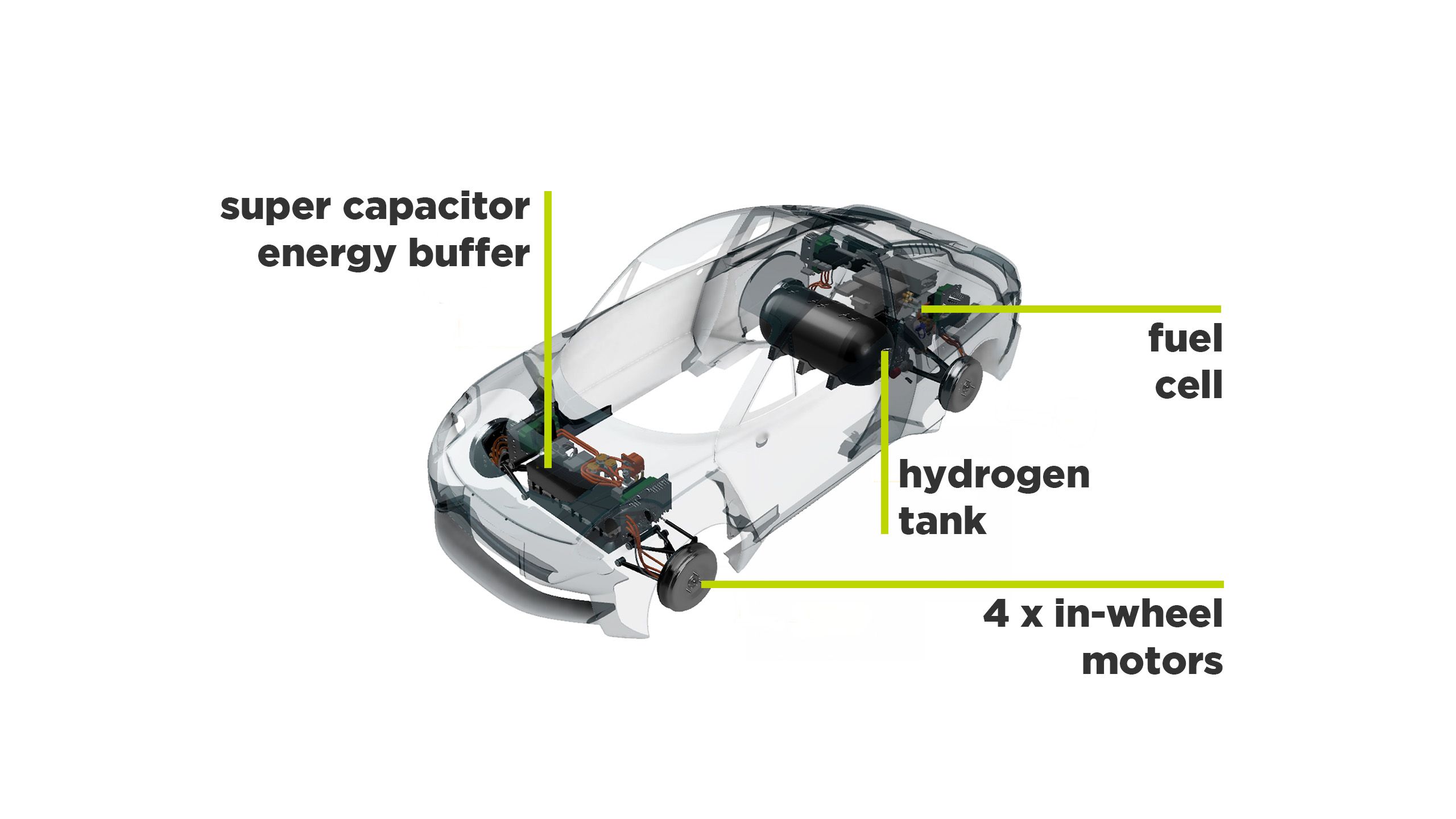

Hydrogen fuel cells use hydrogen (H2) to create electricity, and the only waste they produce is water. The electricity created moves the wheels of the car.

But H2 is expensive and takes a lot of energy to produce. Nowadays, a variety of sources of energy are used to produce H2, including fossil fuels, meaning that it can still have a carbon footprint. In the future, it is hoped that it will be mostly produced using renewable energy – what is called “green hydrogen”.

Spowers didn’t invent hydrogen fuel cells, nor hydrogen fuel cell-powered cars. What’s unique about Riversimple cars is their efficiency. It starts from the premise that car engines, or fuel cells in the case of hydrogen-powered cars, are unnecessarily big, built for a peak power that’s hardly ever used when driving. For 90% of the time, cars only need 20% of this power. So Riversimple has made the Rasa’s fuel cell five times less powerful than a conventional car – and lighter.

“Pivoting is terribly fashionable... But it basically means you haven't thought it through properly in the first place”

Hydrogen (H2) takes a lot of energy to produce. 'Green hydrogen' is mostly produced using zero-carbon, renewable sources of electricity.

Hydrogen (H2) takes a lot of energy to produce. 'Green hydrogen' is mostly produced using zero-carbon, renewable sources of electricity.

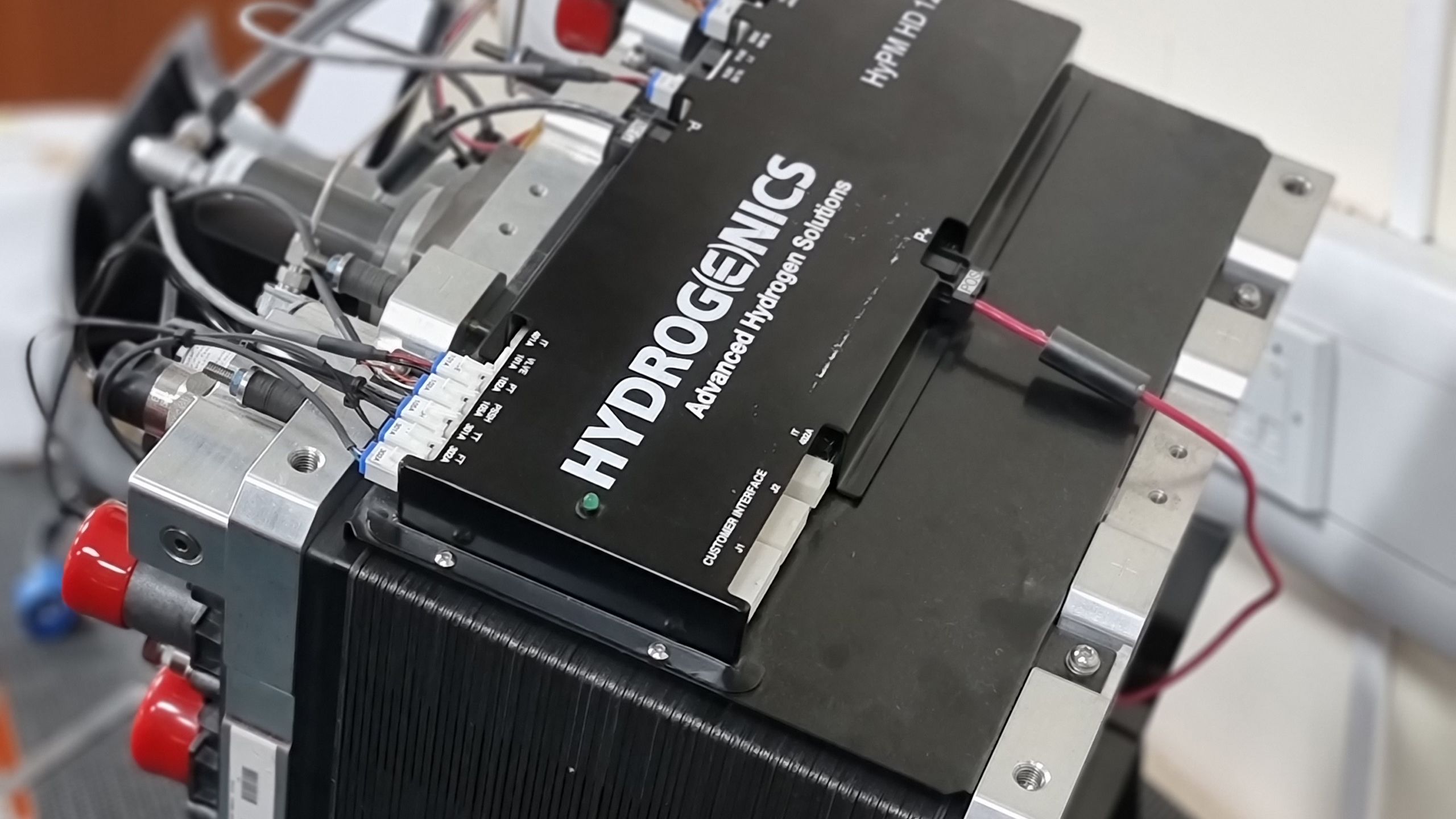

The fuel cell of a Riversimple Rasa car is less powerful – and crucially, lighter – than the unnecessarily big engines of conventional cars.

The fuel cell of a Riversimple Rasa car is less powerful – and crucially, lighter – than the unnecessarily big engines of conventional cars.

GLOSSARY

GREEN HYDROGEN

Producing hydrogen, like electricity, requires energy. “Green” hydrogen is at present mostly produced using zero-carbon, renewable sources of electricity (such as wind and solar), to separate water into hydrogen and oxygen through electrolysis. This means it is entirely carbon-free. It can also be produced from any biomass source; other methods are not yet commercialised, such as using solar energy directly to split water.

However, nowadays the main energy source used to produce hydrogen is natural gas, which emits large quantities of CO2 (although this is 50% more efficient than electricity from natural gas).

HYDROGEN FUEL CELL

A hydrogen fuel cell converts the chemical energy of hydrogen and oxygen into electricity (which can then be used to move a car). Unlike a battery, it doesn’t store electricity but creates it out of hydrogen and air; it is in fact the same process as electrolysis, but in reverse.

CAPACITOR

A simple electrical component that stores electrostatic energy. It can only contain a small amount of energy, but is much quicker at absorbing and releasing electricity than a battery.

REGENERATIVE BRAKING

An energy recovering mechanism that slows down a car by converting its kinetic energy (the energy created by the car’s movement) into electricity, which can be stored, or used immediately.

Efficient ‘regenerative braking’ provides the peak power needed for the remaining 10% of the time: when the car brakes, this in turn creates energy that can be recovered. Instead of being stored in a battery, which would make the car heavier, in a Riversimple car this energy is absorbed by capacitors, which can absorb and release a small quantity of energy very quickly. This energy is ready to be used when the car accelerates – making up for the lower power of the fuel cell.

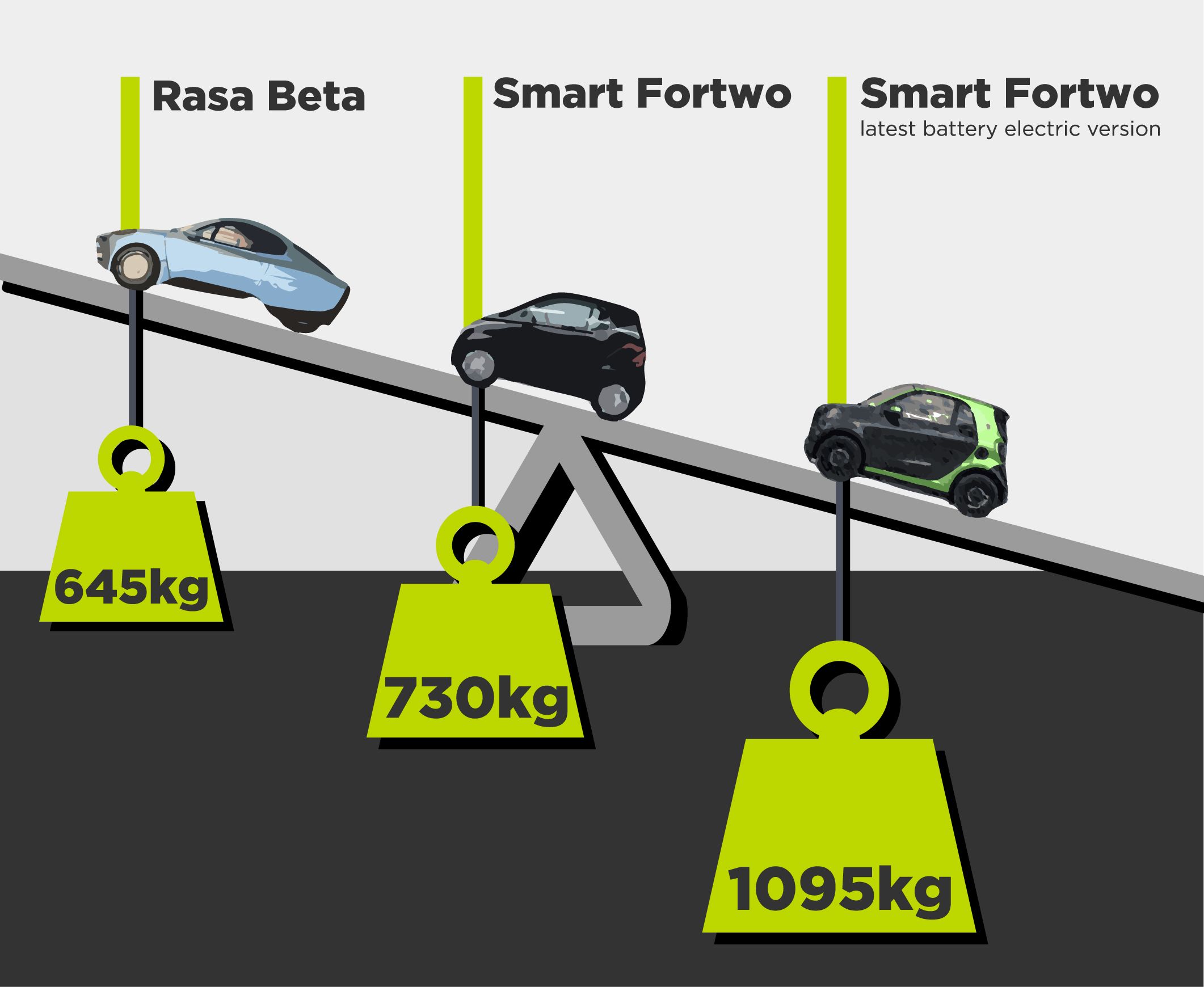

The car is lighter so uses less energy to move. A lighter car also means narrower tires, removing the need for power steering, which makes the car even lighter and so on: through a virtuous circle, the car becomes more efficient in terms of both energy and running costs.

And a more efficient car is at the heart of the company’s business model: to never sell a car.

Riversimple's two-seater Rasa Beta weighs just 654kg – lighter than conventional competitors such as the Smart Fortwo.

Don’t sell a product – sell a service

“If you sell a product, you make more money by selling more, so your direct profit motive is to maximise resource consumption,” says Spowers. “If you sell cars, your interests are obsolescence and high running costs” – in other words, the direct opposite of what customers want – “because the shorter the life of the car, the more cars the market can absorb every year”.

Instead, the company will sell transportation as a service, under a subscription model: for a fixed monthly price and a mileage rate, the consumer will have the use of the car and all associated costs covered – including fuel, insurance and maintenance. The mileage rate remains the same no matter the age of the car, but the fixed price goes down as the car gets older.

It’s in the company's interest to make high quality and efficient cars, as it pays for repairs and fuel. The car maker is also incentivised to make the car as long-lasting as possible: as long as it runs, the car will generate revenue for the company. “Instead of obsolescence and high running costs, our interest is in longevity and low running costs,” says Spowers.

He adds: “We're not designing a car to build as a product to sell. We design a car to build as a revenue-generating asset on our balance sheet. The longer it generates revenue, the more profitable it is, and the longer we can amortise them, the cheaper we are in the marketplace.”

“Instead of obsolescence and high running costs, our interest is in longevity and low running costs”

The fully circular ambition of Riversimple doesn’t stop there: the company intends to use the same principle with its suppliers. “We don’t want to buy the components for our car, but we want to pay for the service of the components. And we want those tier-one suppliers not to buy the components in their subsystem from their suppliers, but to pay for the service,” says Spowers.

It’s just good business sense, Spowers argues – the product doesn’t leave your balance sheet and you make an income from it: “We don't want any suppliers to do this just because we want them to. We want them to do it because it's better business for them.”

Riversimple is currently working on this full-loop circular system with Swansea University and the University of Exeter as part of the £2.3m Circular Revolution project. The idea of selling a service instead of a product could even apply all the way up the supply chain to the raw materials, according to Spowers: mining companies would sell their metal as a service, keeping the product as a revenue-generating asset that’s infinitely recyclable – ultimately decoupling its revenue from any mining activity.

Applying the “sell a service, not a product” model all the way up the supply chain would, however, involve thousands of calculations, every month and on every car, Spowers admits. “Paperwork could defeat the whole system,” he adds. “But it's a perfect problem to be solved by blockchain.”

Importantly, Riversimple will open-source its technology – though not before going to market: Spowers explains how important it is for the business to be the brand that got there first. But ultimately, Spowers hopes to see his idea copied and spread as far as possible. That would be good for the company (amid the threat of a “standards war”, widespread adoption of the same standards on things like supply chain volumes makes good business sense). It would also be good for rest of us, helping to overhaul our entire system of car use and ownership.

HRH The Prince of Wales – a long-time champion of sustainability – is among those to have taken a test drive in Riversimple's Rasa.

HRH The Prince of Wales – a long-time champion of sustainability – is among those to have taken a test drive in Riversimple's Rasa.

Riversimple's business model means it's in their interest to make high quality, efficient cars, as it will pay for repairs and fuel.

Riversimple's business model means it's in their interest to make high quality, efficient cars, as it will pay for repairs and fuel.

Spowers wants the auto industry to shift away from consumers buying new cars with high running costs and a short lifespan.

Spowers wants the auto industry to shift away from consumers buying new cars with high running costs and a short lifespan.

Stakeholder governance – but not as you know it

The importance of good governance became apparent to Spowers as soon as Riversimple started to consider raising capital. “I realised that that funding brings responsibilities and rights,” he says.

The current economic system favours shareholder primacy, meaning the purpose of a company is to generate as much profit as possible for its shareholders. “Business models that evolved in the last century or two make more money by externalising costs on society,” says Spowers. “They're all too often rewarded for the opposite of what society needs.”

Spowers, who had set up the company as a for-profit, purpose-led business from the start, explored different models of governance to give equal power to all the stakeholders concerned with the activities of the company: customers, investors, the environment, the community, employees and commercial partners.

With the help of economists and lawyers, Riversimple developed its “Future Guardian Governance” model, a first-of-its kind structure where stakeholders become shareholders. Each stakeholder group is represented by a specially set up custodian company limited by guarantee. The custodian companies hold the six voting shares in Riversimple, but have no equity rights (they have no money involved). Meanwhile, equity shares issued by the company have no direct voting rights: they invest their money in the company and control the voting share of the investor custodian (ie 16.67% of voting rights), but not the voting shares of the other five custodians.

The board’s fiduciary duty is to deliver the company’s purpose while “balancing and protecting” the benefit streams of the custodian shareholders (rather than maximising the value of one), and is answerable to the custodian shareholders.

"There's nothing like it at all, which I think is the brilliance of it"

“There's nothing like it at all, which I think is the brilliance of it,” says Amoe Mkwena, associate in the infrastructure, energy and resources team at international law firm Hogan Lovells, who has been advising Riversimple on its governance as part of the firm’s pro-bono activities.

She explains Riversimple’s model differs from what corporate law normally prioritises – profit. “It creates a little bit of a tension with this idea that all companies should just be profitable, and I think that's what makes it exciting and unique… [but] we have to work a little bit harder to try and get it to fit within the principles that are entrenched in law.”

For example, in corporate law in general, directors’ fiduciary duty is to work towards “the good of the company – which actually means profit”, says Mkwena. Riversimple’s governance, meanwhile, makes it as much about profitability, as about “key issues, such as the environment and looking after customers and other stakeholders”.

While this has put off some investors, others have been attracted by the company’s governance model, according to Spowers. And while it might look a bit cumbersome for a small startup, it is designed for the big company Riversimple hopes to become.

“We think that the business model is really what makes the company sustainable and circular. But it's the governance model that makes it regenerative.”

Riversimple's custodian companies are represented by (from top left, clockwise): Bill Whyman, Peter Davies OBE, Jackie Royal, Juergen Maier CBE, Leon Kamhi, Peter Lang.

Riversimple's custodian companies are represented by (from top left, clockwise): Bill Whyman, Peter Davies OBE, Jackie Royal, Juergen Maier CBE, Leon Kamhi, Peter Lang.

Amoe Mkwena of Hogan Lovells has been advising Riversimple on its governance as part of the firm’s pro-bono activities.

Amoe Mkwena of Hogan Lovells has been advising Riversimple on its governance as part of the firm’s pro-bono activities.

On the cusp of a breakthrough?

After two decades of operation, Riversimple is ready to bring its first car to market. But this breakthrough rests on one crucial variable: fundraising.

“Raising funds hasn't always been easy,” Spowers explains. “But more and more, the world is getting our way”. Hydrogen technology is “much more on the radar” nowadays than in the 2000s; the idea of renting a car as a service rather than buying it is much more mainstream for customers; and stakeholder governance, while still off-putting to some investors, is more widely accepted, the engineer argues. Meanwhile, the enthusiasm for ESG (environmental, social and governance) investing means more capital seeks sustainable investments.

Nevertheless, because Riversimple is innovating on many different fronts, some still consider it a risky bet. But Spowers argues that all these innovations are consistent – that they are “complementary and mutually reinforcing and that reduces the risks and barriers”.

Riversimple has raised £15m in investment and £9m in grants or tax breaks over the years. That can seem like a lot in pre-revenue phase, Spowers says, but car making is very capital-intensive. The company aims to raise £200m over the next four years, which would enable it to make 10,000 cars a year and become profitable. “But it does depend entirely on capital,” Spowers says. “One thing that's outside our control.”

In the long term, Riversimple plans to have several small plants – each producing around 5,000 cars a year – operating in different regions of the UK and abroad.

“I may be wrong, but I certainly feel that we've addressed all the problems and aligned all the interests, in the governance as much as the business model,” Spowers says. “Those are really where the barriers lie to sustainability – not in technology.”

For Hogan Lovells’ Mkwena, it’s the people behind the company that makes a breakthrough in this extremely tough market possible.

“They're incredibly passionate and unwavering about [their] objectives,” she says. “I think what a lot of organisations can learn from them is ensuring that the leaders, or the people right at the top, know about and care about the objectives of the company, and then that has a trickle-down effect to everything else that you do.”

Video footage courtesy of Riversimple; photo credits: Riversimple; Hogan Lovells

In 2016 the UK's Royal Automobile Club recognised the company's "genuine contribution to motoring innovation".

In 2016 the UK's Royal Automobile Club recognised the company's "genuine contribution to motoring innovation".

Based in mid-Wales, Riversimple plans to set up several plants around the UK and abroad.

Based in mid-Wales, Riversimple plans to set up several plants around the UK and abroad.

This immersive feature was produced by Pioneers Post in partnership with Hogan Lovells and HL BaSE, the firm’s impact economy practice.

Get in touch if you'd like to tell your story.

J O I N T H E I M P A C T P I O N E E R S

SUPPORT OUR IMPACT JOURNALISM

As a social enterprise ourselves, we’re committed to supporting you with independent, honest and insightful journalism – through good times and bad.

But quality journalism doesn’t come for free – so we need your support!

By becoming a fully paid-up Pioneers Post subscriber, you will help our mission to connect and sustain a growing global network of impact pioneers, on a mission to change the world for good. You will also gain access to our ‘Pioneers Post Impact Library’ – with hundreds of stories, videos and podcasts sharing insights from leading investors, entrepreneurs, philanthropists, innovators and policymakers in the impact space.