First global social enterprise census reveals ‘one of the largest movements of our time’

Landmark research counts millions of social enterprises worldwide

How many social enterprises are there worldwide? Finally, we have an answer to this perennial question in a new report which highlights social enterprises’ unique characteristics, the challenges they face and their crucial importance in the global pandemic recovery.

There are approximately 11m social enterprises across the world, according to the most comprehensive data ever gathered, published in a report today by the British Council and Social Enterprise UK.

The research, More in Common: The Global State of Social Enterprise, for the first time aims to identify how many social enterprises – businesses driven by a social or environmental purpose – exist globally.

In the report foreword, Dr François Bonnici, director of the Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship and head of social innovation at the World Economic Forum, said: “This historic report demonstrates how social enterprise is one of the largest movements of our time.”

The movement is driven by millions of people developing the kinds of companies we need in the 21st century

As well as estimating the global number of social enterprises, the report, which brings together a series of pieces of research carried out since 2015, aims to give a flavour of what social enterprises are like in different countries, exploring their differences and similarities. It also looks at how governments and others are supporting social enterprises, and the challenges that they face.

The researchers pointed out that their method of calculating the total global number of social enterprises had limitations, being based on figures from 27 countries and territories, and then estimates for the rest of the world. However, they added: “We are cautiously confident in our conclusion that there are many millions, and perhaps around 11m businesses that could be recognised as social enterprises around the world, however they identify themselves…they are likely creating many millions of jobs and turning over many billions of pounds every year.”

Bonnici said: “[The movement] does not have a visible leader or figurehead, or feature media-made unicorn successes, but it is rather driven by millions of people developing the kinds of companies we need in the 21st century.

“They are significant in number and are present in every community and society around the world. We know that social enterprises are essential in the effort to recover from the pandemic and drive more inclusive, sustainable economies and societies.”

SOCIAL ENTERPRISE SNAPSHOT

Anaesthetist Kibret Abebe sold his house to finance the launch of Tebita Ambulance in 2008 in response to the country’s lack of emergency transport which meant that too often traffic accident victims died on the way to hospital. The social enterprise cross-subsidises its work for those in need by providing first aid training and medical assistance services to commercial clients. “Tebita’s business model proves that profitability and social impact are not mutually exclusive,” he says.

SOCIAL ENTERPRISE SNAPSHOT

Folkcharm in Thailand works with artisans and home-based local craftswomen, like the Lum Nam Huay Natural Cotton Weaving Group members pictured here. Materials are organic and chemical-free and 50% of sales goes directly to the makers. Off-cuts are upcycled and 90% of packaging is recycled or biodegradable. Through its products, the business increases awareness of traditional crafts and slow fashion.

SOCIAL ENTERPRISE SNAPSHOT

Cultural centre Lá da Favelinha in Brazil “ was born and raised in the favela”, says founder Kdu do Anjos. It offers free language, music, dance and art classes, welcoming more than 500 people a week and pays for the services of more than 70 young independent dancers, DJs, teachers and creatives. Its Remexe fashion label project was led by LGBTQ+ and non-white females, and specialised in upcycling genderless fashion.

SOCIAL ENTERPRISE SNAPSHOT

Hathay Bunano (which means ‘hand made’) in Bangladesh is a fair trade organisation creating soft toys in clean and safe environments, paying double the average wage of garment factories across Bangladesh. Together with partner Pebble Child Bangladesh, it has created employment for around 8,000 women and exports to 37 countries. “We started it as a way of bringing fairly paid, flexible employment to areas where there is very little opportunity for women,” says founder Samantha Morshed.

Social enterprises are doing well as businesses: they are growing, creating jobs, innovating and making profits. Yet crucially, they are also delivering for people and planet

Young businesses led by young people

The researchers emphasise that social enterprise is defined in different ways and given a variety of names around the world – some of the organisations that the researchers considered social enterprises didn’t even identify as social enterprises themselves. The researchers conclude that the following three characteristics are shared by social enterprises in the majority of countries:

- A significant proportion of their income is earned through trading, selling goods and services in markets.

- They have a commitment to a primarily social or environmental mission above the pursuit of profit.

- They principally direct their surpluses or profits towards that mission.

The researchers point out that social enterprises across the world take a wide variety of legal forms. Some work locally, but some have global reach. They work across all sectors of the economy, including agriculture, heritage, education, health and food.

There is no typical social entrepreneur. But they have commonalities, like passion and flair, and not accepting no for an answer

Social enterprises are much more likely to be led by women than conventional businesses, and they are often headed by young people. What’s more, they are largely young businesses. Social enterprises are increasingly attracting academic attention as well as support from governments around the world.

Although social enterprises face a number of barriers, including access to appropriate finance, many – at the time the research was carried out, which was largely before the Covid-19 pandemic – are optimistic and have plans to grow.

“There is no typical social enterprise or social entrepreneur,” Paula Woodman, the British Council’s head of global social enterprise, said. “But they have commonalities, like passion and flair, and not accepting no for an answer.”

She added that social entrepreneurs were often spurred into action by challenges that they have faced in their own lives. “Often social entrepreneurs will refer to a particular lightbulb moment or an experience that drives them,” she said.

Dan Gregory, director of international and sustainable development at Social Enterprise UK, said: “This research gives us an inspiring picture of social enterprise around the world. Social enterprises are doing well as businesses: they are growing, creating jobs, innovating and making profits. Yet crucially, they are also delivering for people and planet – for women, disadvantaged people, minority groups and the environment – a means to deliver our common goals.”

What the data reveals

The following data is drawn from the surveys of social enterprises around the world.

Young organisations

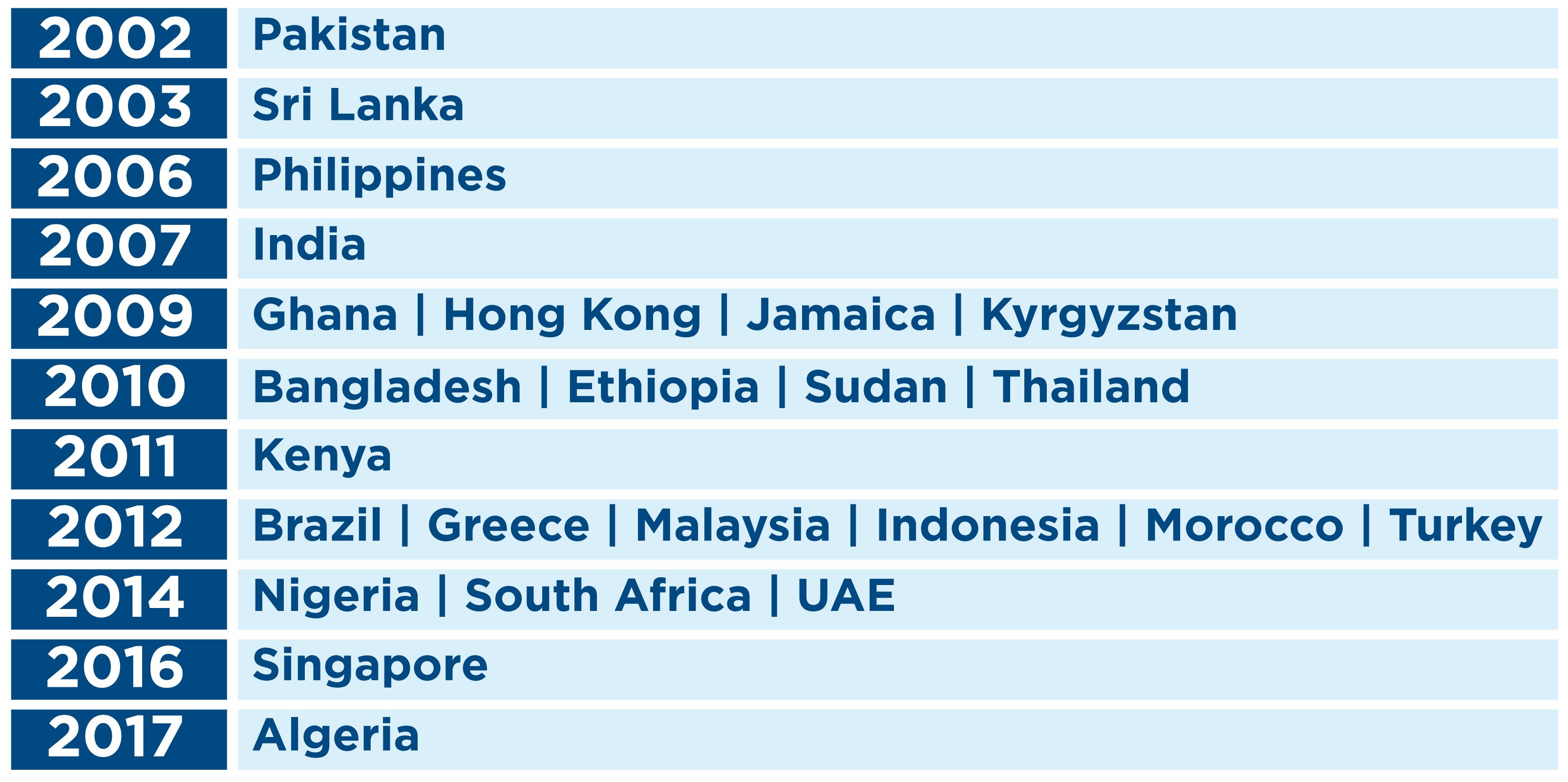

The research found that social enterprises across the world are often young organisations. The average year of establishment across all the countries is 2010. Singapore and Algeria have the newest social enterprises, while social enterprises in Sri Lanka and Pakistan are older.

Women leaders

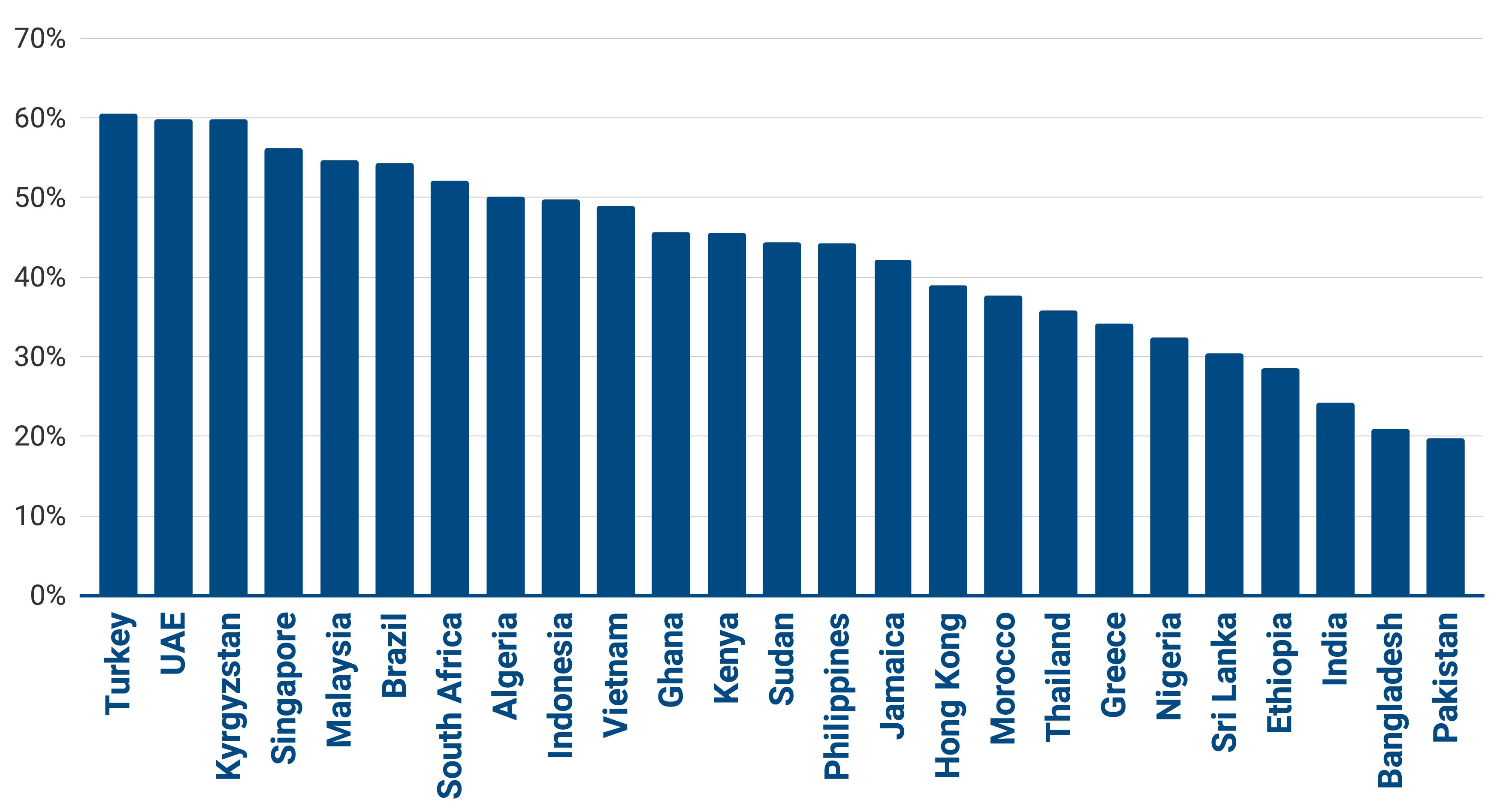

The researchers said that in almost every country studied, social enterprises were more likely to be led by women than businesses more widely, pushing forward gender equality.

The greatest proportion of female leaders were found in Turkey, UAE and Kyrgyzstan. There were fewer female leaders in Bangladesh and Pakistan.

Percentage of social enterprises with women leaders

Young leaders

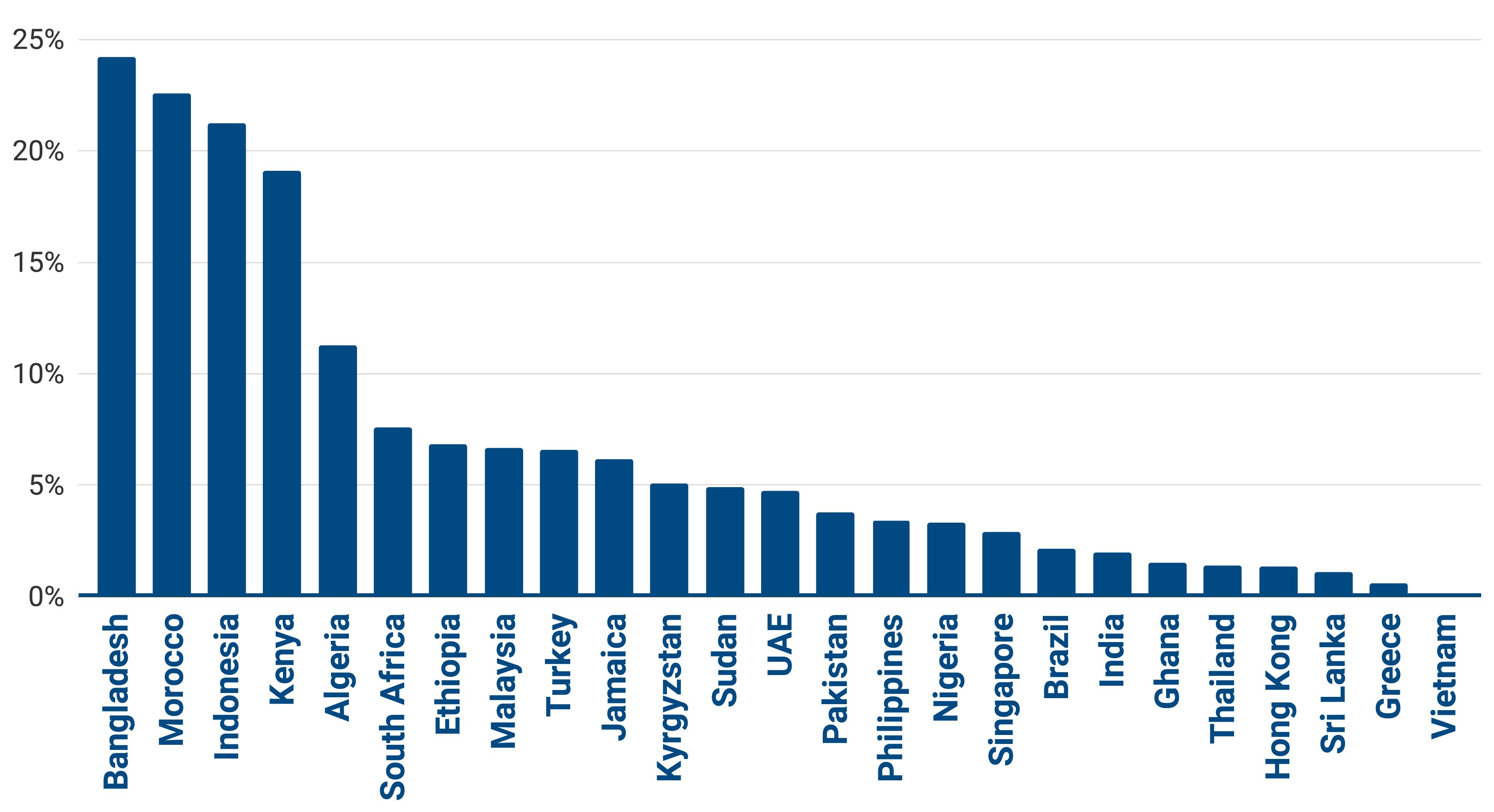

Social enterprise leaders are often young. Bangladesh, Morocco and Indonesia had the highest proportion of social enterprises led by under 24-year-olds, while Greece, Ghana, Hong Kong, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Vietnam had few social enterprises led by young people.

In most countries, social enterprise leaders were aged between 25 and 44. Jamaica and Sri Lanka had the highest proportion of leaders aged over 65 years old.

Percentage of social enterprises with leaders aged 16-24

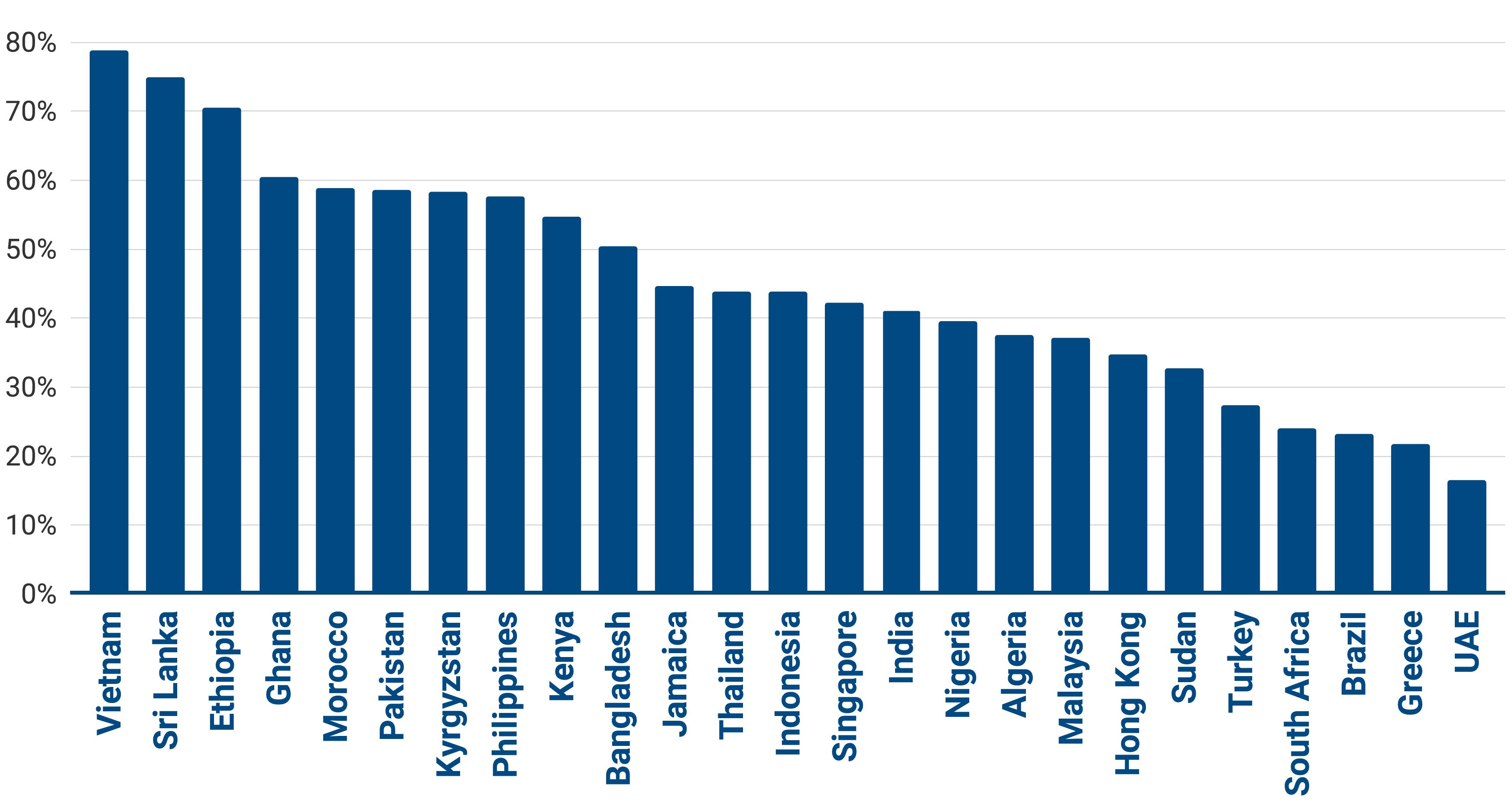

Percentage of social enterprises with leaders aged 25-44

Profit

Social enterprises tend to more commonly report making a profit in Vietnam and Sri Lanka. In South Africa, Brazil, Greece and UAE less than a quarter make a profit.

Percentage of social enterprises that report making a profit

Growth

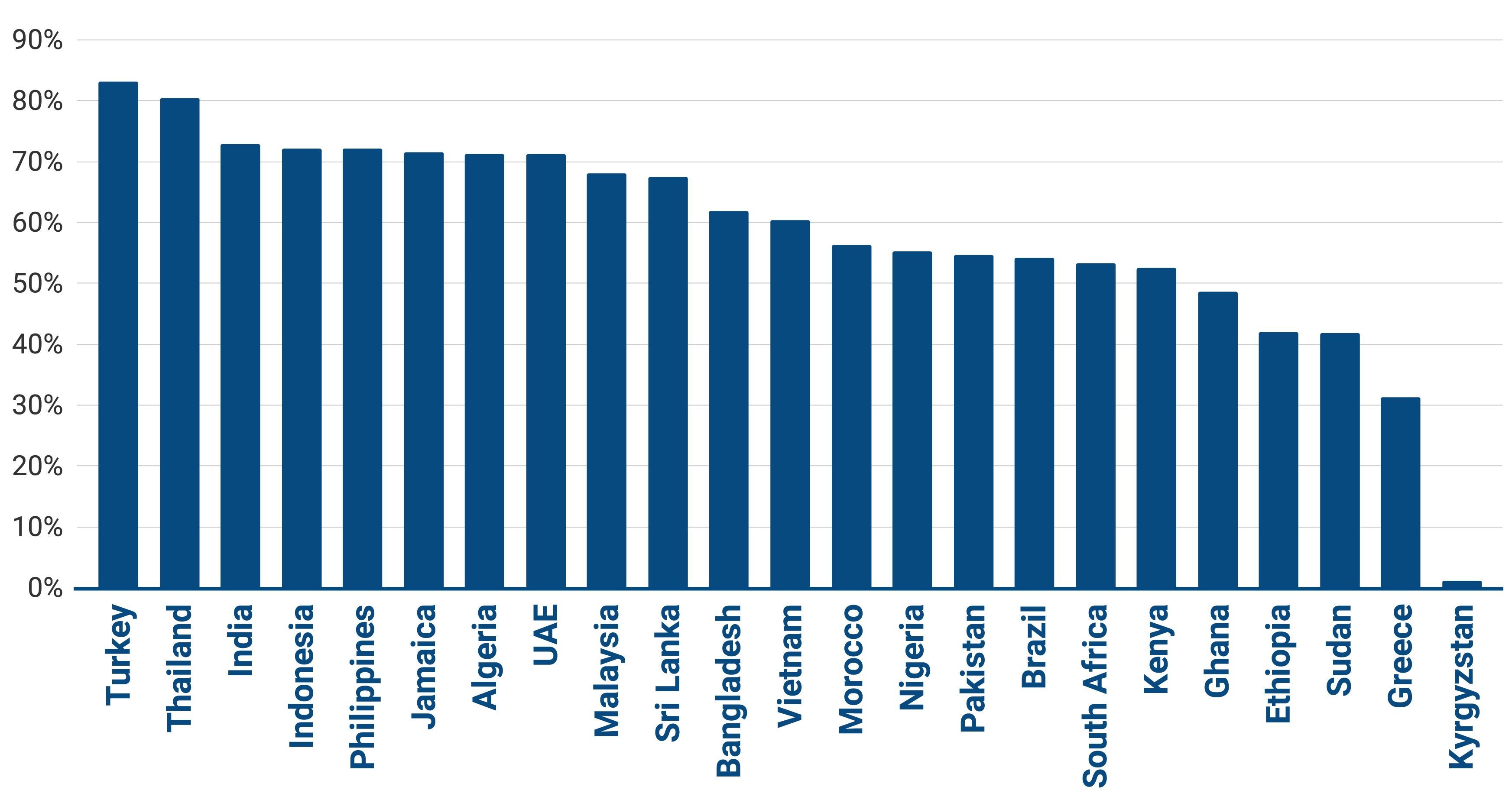

The researchers conclude that most social enterprises around the world are optimistic and have plans to grow. More than half of all social enterprises surveyed were planning to achieve growth through developing new products and services “reinforcing the idea of social enterprises and engines of innovation”, according to the researchers.

Percentage of social enterprises planning to develop new products and services

For all the data, see the full report here.

We share similar silver bullets

Huda Jaffer, director, Selco Foundation, India

Selco Foundation is a research and development lab for social enterprises, governments and community based organisations. We work with last-mile social enterprises to help them stabilise and grow, using clean energy as a catalyst to alleviate poverty, particularly in climate-vulnerable settings.

In India, the term social enterprise is very loosely used – there are lots of different types of structures and the enabling conditions differ in different states. Common elements are working on critical needs and with vulnerable populations. At the same time, there are many other enterprises beginning to take seriously the climate agenda and inclusion.

In a country like India, the scope for social procurement is huge – and this is where certification for social enterprises could be useful. The Social Enterprise World Forum is currently piloting a verification scheme which could really help with this.

Challenges for people working in communities include finance of the right type and quantity to support social enterprises to sustain and survive. What’s more, high risk innovation capital for communities is completely missing.

There was a silver lining to the Covid pandemic because before, there were stakeholders who didn’t believe in local and decentralised ecosystems. Now they are thinking, ok we need this, because during the pandemic supply chains were cut off and centralised systems didn’t work for people. There is a focus on decentralisation now and that, by default, gives rise to social enterprise.

If we have the right champions in place, for example in government, it can really move the needle. There are some positive levers that I am really hoping get scaled. For example, the health systems during Covid were really exposed. Now, 12 states have moved towards powering their health systems with green energy, and they are using green design in new buildings. This is the kind of needle-moving stuff I’m talking about.

There is a definite commonality among social enterprises across the world. The pain points are similar, and there are similar silver bullets. While their working conditions may be different, they have the potential to learn from each other. A common thread among all social enterprises is that their mission and philosophies are similar.

The establishment of robust evidence is often understood to be an important step, or even a prerequisite, in the policy development process

From robust evidence to well-informed policy

In 2002, the UK government’s Department for Trade and Industry published Social Enterprise: A Strategy for Success. This was the first formal government strategy explicitly aimed at supporting social enterprises, according to the research.

Since then, said the researchers, “the Scottish government has arguably led the way”.

At the end of 2021, the EU published a new Social Economy Action Plan which has been well received.

The researchers point to a range of notable policy developments across the world, including:

- The Jamaican government’s programmes to promote social enterprise during the past few years.

- Social enterprise legislation drafted in Ghana.

- Changes in legislation in Ethiopia to allow NGOs to trade goods and services.

- The Malaysian government’s active role in recognising and promoting social entrepreneurship through its Malaysian Global Innovation and Creativity Centre (MaGIC) and the Malaysian Social Enterprise Blueprint 2015-18.

- Recognition of the term ‘social enterprise’ as a distinct type of organisation in Vietnam’s Enterprise Law in 2015, which gave investment incentives and access to foreign aid.

In many countries, the researchers said, there is no explicit legislation for social enterprise nor a distinct type of legal form. It is important to have co-ordinated and constructive advocacy on behalf of social enterprises to take policy forward.

The research highlights that in some countries, the publication of research helped to influence developments in policy and the ecosystem of support for social enterprise.

“The establishment of robust evidence is often understood to be an important step, or even a prerequisite, in the policy development process,” the researchers said. In Bangladesh, for instance, the research was followed by the development of a National Impact Investment Strategy and Action Plan. And in Indonesia, the research helped to underpin the inclusion of social entrepreneurship in the National Development Plan.

How the data was gathered

The global report is based on studies led by the British Council in 27 countries and territories. These represent 40% of the world’s population, including developed and developing, stable and fragile states. They are:

Algeria, Bangladesh, Brazil, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Malaysia, Morocco, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore, Ghana, Greece, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Jamaica, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Sudan, Thailand, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, Vietnam.

The research was carried out between 2015 and 2020, and led by local experts, adapted to the context, so the results aren’t always directly comparable. The researchers emphasise that the report “cannot therefore claim to provide an accurate comparison of the state of social enterprise across the world, but rather give a flavour and insight into trends across diverse contexts”.

The estimate of the total global number of social enterprises was based on figures for the number of social enterprises in specific countries that had been identified during this research, data on the numbers of social enterprises and other types of businesses published by other researchers and an average figure for the number of social enterprises per person in the global population.

Read more about research into social enterprise around the world

There is a definite commonality among social enterprises across the world. While their working conditions may be different, they have the potential to learn from each other

What next?

The research comes as the global social enterprise movement is “maturing”, said Bonnici. He pointed to greater collaboration taking place, for example, through the Global Alliance for Social Entrepreneurship, hosted by the Schwab Foundation, which launched in 2020 as a response to the Covid-19 pandemic, and social entrepreneur-led organisation Catalyst 2030.

“Working in this new way, across fellow actors and with global evidence to back the case, we seek to engage public and private leaders to recognise the value and engage their support for the movement,” he said.

Similarly, the British Council and Social Enterprise UK said they hoped that the research would equip policy makers, social investors and others with information and evidence to more effectively support and measure the growth of social enterprise and the impact economy around the world.

Paula Woodman said she wanted to see more countries where the social enterprise movement was less developed being included in the conversation. She added: “I hope the report will give those who don’t know about social enterprise real solid evidence and provide a framework to progress and support the movement.”

This was only the beginning, said Bonnici: “There is an urgent need for additional support for future research to build on this first dataset.”

SOCIAL ENTERPRISE SNAPSHOT

87 per cent of Egyptian men believe a woman’s most important role is to cook and look after the home. Egypt’s Entreprenelle offers women education and training, and entrepreneurship development. Started by Rania Ayman when she was in her early 20s, the social enterprise has now worked with more than 100,000 Egyptian women.

SOCIAL ENTERPRISE SNAPSHOT

Jobs are hard to come by for many young people in Jamaica, and being deaf can hamper their chances further. Deaf Can! Coffee is run by and for deaf people, training and employing them as baristas. The enterprise contracts out baristas to coffee shops, as well as operating its own mobile pop-up cafes.

SOCIAL ENTERPRISE SNAPSHOT

Madlug is a social enterprise in Northern Ireland that gives specially-designed luggage to children in care across the UK. Those donations are funded by sales of Madlug’s own-brand backpacks, gym bags and accessories to consumers as well as to corporate customers. The company sells around 500 to 600 bags a month and has given away more than 45,000 bags to date.

SOCIAL ENTERPRISE SNAPSHOT

Luüna in Hong Kong is a purpose-driven period wellness company. It offers period products, education, training and a supportive community, as well as combating period poverty. To date it has provided more than 50,000 organic cotton pads to communities in need.

This immersive feature was produced by Pioneers Post, the leading global news platform for mission-driven businesses, social entrepreneurs and impact investors, in partnership with the British Council.

Get in touch if you'd like to work with us to tell your story.

J O I N T H E I M P A C T P I O N E E R S

SUPPORT OUR IMPACT JOURNALISM

As a social enterprise ourselves, we’re committed to supporting you with independent, honest and insightful journalism – through good times and bad.

But quality journalism doesn’t come for free – so we need your support!

By becoming a fully paid-up Pioneers Post subscriber, you will help our mission to connect and sustain a growing global network of impact pioneers, on a mission to change the world for good. You will also gain access to our ‘Pioneers Post Impact Library’ – with hundreds of stories, videos and podcasts sharing insights from leading investors, entrepreneurs, philanthropists, innovators and policymakers in the impact space.