A ‘winning coalition’ for healthcare entrepreneurs

From supermarket check-ups in Nicaragua to mini-pharmacies in east Africa, pioneering social enterprises want to change the world by making healthcare accessible to all. We explore how support from the Philips Foundation – backed by 130-year-old healthcare technology company Philips – is key to their success. The latest in our special series with EVPA on the role of corporate social investors.

Across the globe, social entrepreneurs are taking on the thorny challenge of making healthcare available to all. From bringing remote healthcare technology to African villages, to pop-up health checks in shopping malls in Nicaragua, their mission is to serve people who would otherwise struggle to see a doctor.

Crucial to the success of these innovations, though, are supportive partners – such as Netherlands-based Philips Foundation, which helps social enterprises that aim to reduce health inequality or improve healthcare access.

The foundation’s related company, Philips, was founded in 1891 and is well-known as a maker of domestic appliances. But for the past decade, it has decided to focus entirely on healthcare technology, specialising in diagnostics, image-guided therapy, telehealth and all the digital components that come with it.

Aligned with the company’s focus on healthcare, Philips Foundation’s mission is to reduce health inequality by providing access to quality care for disadvantaged communities.

The foundation invests in entrepreneurs best positioned to provide healthcare solutions on the ground: alongside grants to nonprofit organisations, it now also provides loans and equity investment.

For the foundation, it is essential to build a close relationship with the entrepreneurs it supports, understanding their impact and their line of business as well as the obstacles they face. And in turn, the social innovators can learn from 130 years of experience at Philips.

Telehealth connects remote villages with doctors in sub-Saharan Africa

Telehealth connects remote villages with doctors in sub-Saharan Africa

Technology brings essential health checks to Nicaraguan shopping malls

Technology brings essential health checks to Nicaraguan shopping malls

An annual gathering on European corporate philanthropy and social investing

Join EVPA's C Summit on 15-16 November in Porto to explore how corporate social investors can achieve more impact through strategic alignment with their related company.

Healthy Entrepreneurs: mini-pharmacies and more in east Africa

In 1987, world leaders signed the Treaty of Bamako – a pledge to ensure every citizen in sub-Saharan Africa would have access to free healthcare. Yet in 2021, many of the 670m people living in rural areas in the region still have no access to basic medical services.

“In remote villages in Uganda, in Kenya, in sub-Saharan Africa, [healthcare] products are not available, the knowledge about healthcare is poor. Things we, in the West, consider a given aren't there,” says Dutch social entrepreneur Joost van Engen.

A former canned meat export manager who later worked on distributing affordable pharmaceuticals in developing countries, Van Engen saw first hand that governments and aid agencies had failed to deliver on the Bamako pledge. But he also believed there was a solution: entrepreneurship. That’s why, in 2012, he founded Healthy Entrepreneurs, a social enterprise that helps primary healthcare and medicines to reach remote villages in Uganda, Tanzania, Kenya and Burundi. It does this by enabling villagers to start and sustain their own mini-pharmacies, where they can provide informed health advice and sell basic medicines.

These entrepreneurs are often recruited among “community health workers” – respected figures, often women, who have been elected by village members to deliver health advice, but who are poorly trained and equipped. Once they have completed training with Healthy Entrepreneurs – for which they have to pay a commitment fee of US$40 – entrepreneurs are provided with basic products (such as over-the-counter medicine, sanitary pads and condoms) on credit that they sell to consumers at prices that are about 10% lower than the usual going rate. As the supply chain is overseen from production to distribution by Healthy Entrepreneurs, its entrepreneurs can be sure that the products they sell are reliable and safe.

Telehealth

In 2018, Healthy Entrepreneurs started Doctors at Distance, a telehealth service where participating entrepreneurs can phone a doctor directly so they can offer more thorough consultations and pass on additional advice on treatment or diagnoses. Entrepreneurs are given a solar-chargeable phone and diagnostic tools, such as a device to detect hypertension and diabetes.

Under the programme, elderly people in villages can get regular checks, including blood pressure and blood sugar checks, so people suffering from chronic conditions can be identified and treated. The doctor can remotely prescribe the medicine, which is then delivered at a low cost through the Healthy Entrepreneurs supply chain. “The solutions are there… it isn't so difficult,” says Van Engen.

Beyond improving the health of remote communities, Healthy Entrepreneurs has wider socioeconomic benefits: it creates skilled jobs, provides training, and empowers communities to tackle their own problems. Importantly, it lays the foundations for economic development. “Access to primary healthcare is a precondition to break the cycle of poverty,” says Van Engen.

From canned meat to vital medicine

Setting up Healthy Entrepreneurs didn’t happen overnight. During his previous career, Van Engen had realised that, while he could easily export canned meat to more than 150 countries, well-meaning organisations were not able to deliver vital medicines. The main impediment for this, he says, was the failure to see beneficiaries as customers – and to consider building a sustainable business model that doesn’t entirely rely on donations.

In 2011, Van Engen came across Generic Pharmacy, a company in the Philippines selling generic, affordable drugs instead of the branded, expensive ones sold by the government. For Van Engen, it was an example of the private sector filling a gap created by an underperforming public health system – and “clear proof that it was possible,” he says.

To launch a venture like Healthy Entrepreneurs, finding the right type of capital is crucial, Van Engen explains. Initially, Healthy Entrepreneurs had to use donor money, which wasn’t appropriate to finance a supply chain that needs a flow of capital to cover the upfront purchase of products. So Van Engen focused on raising private investment, and the enterprise is now more than 50% funded by loans, planning to only rely on grants for 10-15% of its income in the coming years.

Social entrepreneurs cannot do everything themselves, and the help of networks and organisations is crucial, Van Engen says. The relationship with Philips Foundation started following Van Engen’s participation in the Ashoka Globalizer programme in 2016, where he worked with a team to develop his strategy and build his business pitch to investors. Philips Foundation co-funded the Doctors at Distance project and deployed Philips’s technology for the company to scale up. “We created a winning coalition together, which is as much about technical and expertise support as it is about investment,” says Van Engen.

Thanks to Healthy Entrepreneurs, essential, affordable medicines make their way to remote areas

Thanks to Healthy Entrepreneurs, essential, affordable medicines make their way to remote areas

Joost van Engen, founder of Healthy Entrepreneurs

Joost van Engen, founder of Healthy Entrepreneurs

Technology connects isolated villages to health services

Technology connects isolated villages to health services

Telehealth: Doctors at Distance connects community health workers in rural villages to doctors

Telehealth: Doctors at Distance connects community health workers in rural villages to doctors

Estación Vital: supermarket health checks in Nicaragua

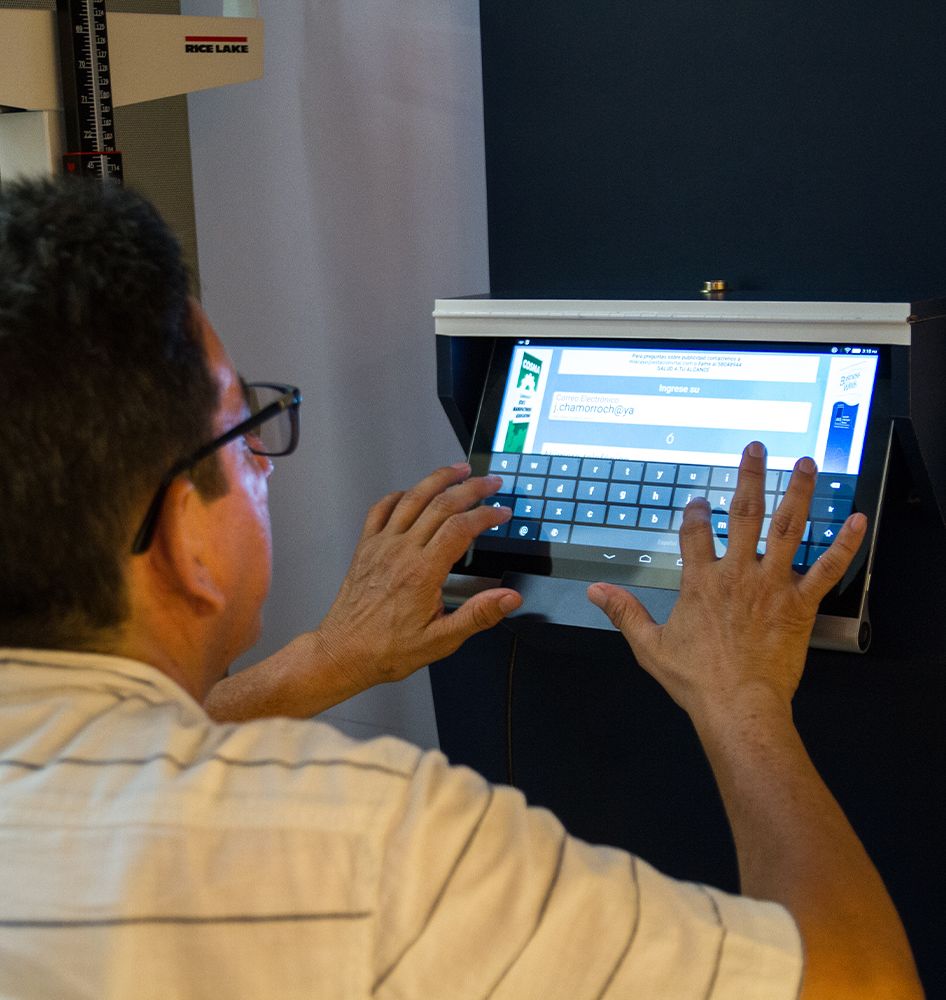

Estación Vital sets up health booths in Nicaraguan shopping malls

Estación Vital sets up health booths in Nicaraguan shopping malls

Estación Vital founder Marcos Lacayo talks to a health booth user

Estación Vital founder Marcos Lacayo talks to a health booth user

Estación Vital founder Marcos Lacayo talks to a health booth user

Estación Vital founder Marcos Lacayo talks to a health booth user

Free health checks enable people to identify their health problems early

Free health checks enable people to identify their health problems early

In Nicaragua, healthcare is free. But the system is underfunded and overstretched, with shortages of staff and equipment, and waiting times to see a doctor so long that people often don’t even try. Meanwhile, growing rates of obesity are threatening public health, increasing risks of cardiovascular disease and diabetes, among others.

Spotting health risks early could make a big difference; however, preventative health is not a government priority. But social entrepreneur Marcos Lacayo had an idea: to make health checks available where people go every week – in supermarkets.

In 2016, Lacayo started Estación Vital, a social enterprise that sets up health kiosks – in appearance similar to a photo booth – at the entrance of supermarkets where people can get free health checks and lifestyle and nutrition advice. Paying customers can undertake further tests and have an appointment with a ‘health coach’ (a trained nutritionist). Earlier this year, Estación Vital also launched an app, allowing users to access the same services from their smartphones. These health checks, even via the app, can help identify obesity, hypertension, diabetes or other conditions in people who wouldn’t otherwise see a doctor.

The social enterprise targets low-income populations in urban environments including favelas (slums). Some 60% of users are women aged between 30 and 50. In Latin America, women are traditionally the head of the household and most commonly in charge of grocery shopping, so teaching healthy eating habits to women means the whole family will benefit. “Women are the boss,” says Lacayo. “They take care of the health of their community.”

Importantly, the social enterprise makes the connection between physical and mental health, which is usually ignored. In Nicaragua, “mental health is a taboo,” says Lacayo. “Seeing a psychologist or psychiatrist here is seen as a weakness.”

The connection between mental and physical health is well established, and even Estación Vital users say they see a connection between traumatic experiences, such as a divorce, and the way they eat. So Estación Vital aims to combine nutritional and emotional solutions to help people change their eating habits. Its nutritionists are trained by psychologists, but the company calls them “coaches” rather than psychologists, so people are more inclined to seek their advice. “It’s all about the wording,” says Lacayo.

Agility in crisis

Being a social entrepreneur in Nicaragua is not easy. The environment is not particularly supportive for entrepreneurs, Lacayo explains, with no tax breaks for people starting their own businesses; corruption is rife. And when he started his enterprise in 2016, Lacayo didn’t expect his country to go through two major upheavals in less than five years.

In 2018, Nicaragua was thrown into a political and social crisis. Hundreds of people were killed in clashes with security forces as protests demanding the resignation of president José Daniel Ortega shook the country. The ensuing economic crisis paralysed the country for months, so Estación Vital had to suspend its activities. As things started to normalise, Lacayo, who became an Ashoka fellow in 2018, set up three kiosks, which at the beginning of 2020 attracted 2,700 monthly users each. This is when Covid-19 hit, and kiosks had to close again.

Lacayo began working with the Philips Foundation through the Ashoka Globalizer programme in 2018. During the pandemic, a team of Philips corporate employees helped Lacayo redefine “post-Covid Estación Vital”, he explains. “It was five months of really digging into the marketing, into the programming, into the development of a product market fit. It was an entire analysis... It opened my mind,” Lacayo adds.

This process led Lacayo to develop the app in addition to the kiosks, and a loan from the foundation (undisclosed amount) helped the company to bounce back. “They pretty much gave me the funding to jumpstart Estación Vital again.”

Estación Vital has now reopened one kiosk, in partnership with supermarket chain Walmart. While the kiosk is key to reaching the most vulnerable populations that don’t have access to technology, the app has extended the reach of Estación Vital, which is now available in Panama, Costa Rica and in southern states of the US. This allows Estación Vital to test the market before launching a kiosk, Lacayo explains. The social enterprise now has 12 staff, including the healthcare team, web developers, the marketing team and two staff at the kiosk.

Whatever obstacles entrepreneurs face there, Nicaragua remains a “great laboratory” to try new ideas as living costs are low, with the potential to launch elsewhere, he says.

“I want to change the world,” says Lacayo. “The real impact that I see is when you change the way people feel and interact with themselves and their environment… And I think this is a good way to do it. It's inexpensive, it's affordable and it can create a big impact.”

Alignment: a win-win relationship

While the Philips Foundation is a separate legal entity from its related company, it benefits from being closely connected to a firm that is “purpose-driven”, says Margot Cooijmans, director of Philips Foundation. “Philips really wants to make a difference in the world. In our own innovative work, we feel strongly supported in every step we take to create equitable access to healthcare for underserved,” she adds. “It’s motivating how capacities of Philips volunteers, added to entrepreneurship, an agile way of working, a lot of outside-the-box creativity, and collaboration with parties with the same mindset, can lead to impact.”

Committing to an investment means really understanding the complexities of the situation on the ground, Cooijmans explains: why something does or doesn’t work; how to scale up an impactful, accessible solution for underserved populations. To do this, Philips Foundation staff meet face to face with the social entrepreneurs it invests in.

“You can look at pictures and you listen to stories,” says Cooijmans. “But if you really walk around and you see the local ecosystem and way of working towards better healthcare, then you understand what is missing or why something is not working, or in what context the patients and the medical service needs to work… and that it is crucial to get people into the healthcare system in the first place.”

The foundation has “a responsibility to provide these people with quality healthcare, because it is our mission and ambition,” Cooijmans adds.

Sophie Faujour, corporate initiative lead at EVPA, which supports and conducts research on strategic alignment between corporates and philanthropic foundations, explains why Philips and Philips Foundation are a good example of this kind of collaboration.

“By operating close to the core competences of Philips as a healthcare technology leader, the foundation can leverage the company’s existing expertise on access to care, as well as any additional corporate resources that help the investees grow and scale their impact,” she says. For example, Estación Vital could rely on the support of Philips’ employees to help the social enterprise adapt to the challenges of the pandemic, while the company can learn from the foundation’s investees.

“Using the expertise, innovation power, talent and resources of Philips in collaboration with other social and purposeful organisations, we can create meaningful solutions that reduce healthcare inequality and impact lives,” says Annette Jung, who supports entrepreneurs at Philips Foundation.

Jung says the company and the 11 social entrepreneurs it supports are on a “bilateral engagement” where both parties invest and benefit – with Philips bringing in skilled volunteers and expertise, while gaining valuable business insights from people who are using its technology.

“The work of social entrepreneurs shows the potential of health technology in other markets,” adds Cooijmans. “That helps us to continue innovating.”

Explore strategic alignment further

The connection between Philips (the company) and the Philips Foundation – and the benefits it creates for both organisations – is an example of what EVPA classifies as ‘business alignment’ – just one way in which corporate foundations can align with their related company to enhance social impact.

“Philips provides the foundation with the unique opportunity to scale impact innovations through the company’s value chain,” says EVPA's Sophie Faujour, while the work of the social entrepreneurs “can inspire and feed into Philips’ business practices, and thus create impact at a global level”.

Find out more about the different forms of strategic alignment in Social Impact through Strategic Alignment. Get in touch with EVPA’s Corporate Initiative for guidance on this and other corporate social investing topics by contacting Nicolas Malmendier.

You can also join the C Summit, EVPA’s annual gathering of European corporate philanthropy and social investing practitioners and experts, on 15-16 November in Porto, Portugal.

This immersive feature was produced by Pioneers Post, the leading global news platform for mission-driven businesses, social entrepreneurs and impact investors. We’re also a social enterprise ourselves, with profits ploughed back to support our community of positive changemakers: you can support our work by subscribing, from just £4 per month (and further discounts for start-ups and students).

Get in touch if you'd like to work with us to tell your story.