Turn off the tap! The river robots that fight ocean plastic

Plastic waste is drowning the natural world: on current trends, there could be more plastic than fish in our oceans by 2050. But what if you could stop the stream of rubbish at the source? That’s exactly what one nonprofit is trying to do by bringing its unusual invention to the world’s dirtiest rivers. Technology that works, though, is just the beginning.

Floating in the middle of the Mekong Delta in Can Tho City, south Vietnam, is a 24-metre-long steel machine with a protruding arm. It doesn’t just look robotic – named ‘Interceptor 003’ – it sounds it too.

Perhaps the scale of the problem has called for an other-worldly solution. There are more than five trillion pieces of plastic littering the world’s oceans, harming marine species and carrying toxic pollutants into our food. The impact on tourism, fisheries and waste management costs global economies an estimated $6-19bn per year.

And the majority of this plastic waste comes from polluted rivers. So The Ocean Cleanup, a Netherlands-based nonprofit, not only collects waste from oceans – it has also started removing plastic from rivers before it’s had the chance to drift downstream.

But there are more than 100,000 rivers around the world, so any effort to ‘turn off the tap’ needs to be replicable at a massive scale. The experts at The Ocean Cleanup reckon their technology can do that. But with big ambitions come big challenges.

Netherlands-based nonprofit The Ocean Cleanup collects waste from oceans – it has also started removing plastic from rivers before it’s had the chance to drift downstream.

Netherlands-based nonprofit The Ocean Cleanup collects waste from oceans – it has also started removing plastic from rivers before it’s had the chance to drift downstream.

Interceptor 003 sits on the Mekong River in Can Tho City, Vietnam, awaiting deployment.

Interceptor 003 sits on the Mekong River in Can Tho City, Vietnam, awaiting deployment.

The robot interceptor

Four years in the making, The Ocean Cleanup’s Interceptor is a clever cleanup system. A large barge sits in the middle of the river. Floating waste is guided towards the opening of the interceptor by a long barrier. A conveyor belt then carries the collected rubbish up into a moving shuttle in the main body of the system, depositing the waste in large bins. Local operators monitor progress via smartphones and when the bins are full they take them to the edge of the river – where the rubbish is collected and taken to local waste management facilities.

The Interceptor is 100% solar-powered, operates day and night without any noise or fumes, and under optimal conditions can extract up to 50,000kg of waste per day. It has been designed for mass production, with the intention of being placed in the world’s most polluting rivers.

The robot is ready – but where in the world to begin?

RIVER RESEARCH

Boyan Slat was just 16 years old when a diving trip in Greece in 2011 led him to research plastic pollution for a school project. One TEDx talk and two years later, the Dutch teen founded The Ocean Cleanup. “We must defuse this ticking time bomb. That has been my mission,” Slat told an audience in 2017.

Data drives all of The Ocean Cleanup’s solutions, and its 100-strong team, including researchers and scientists, studies marine plastic pollution to develop, test and alter their technology.

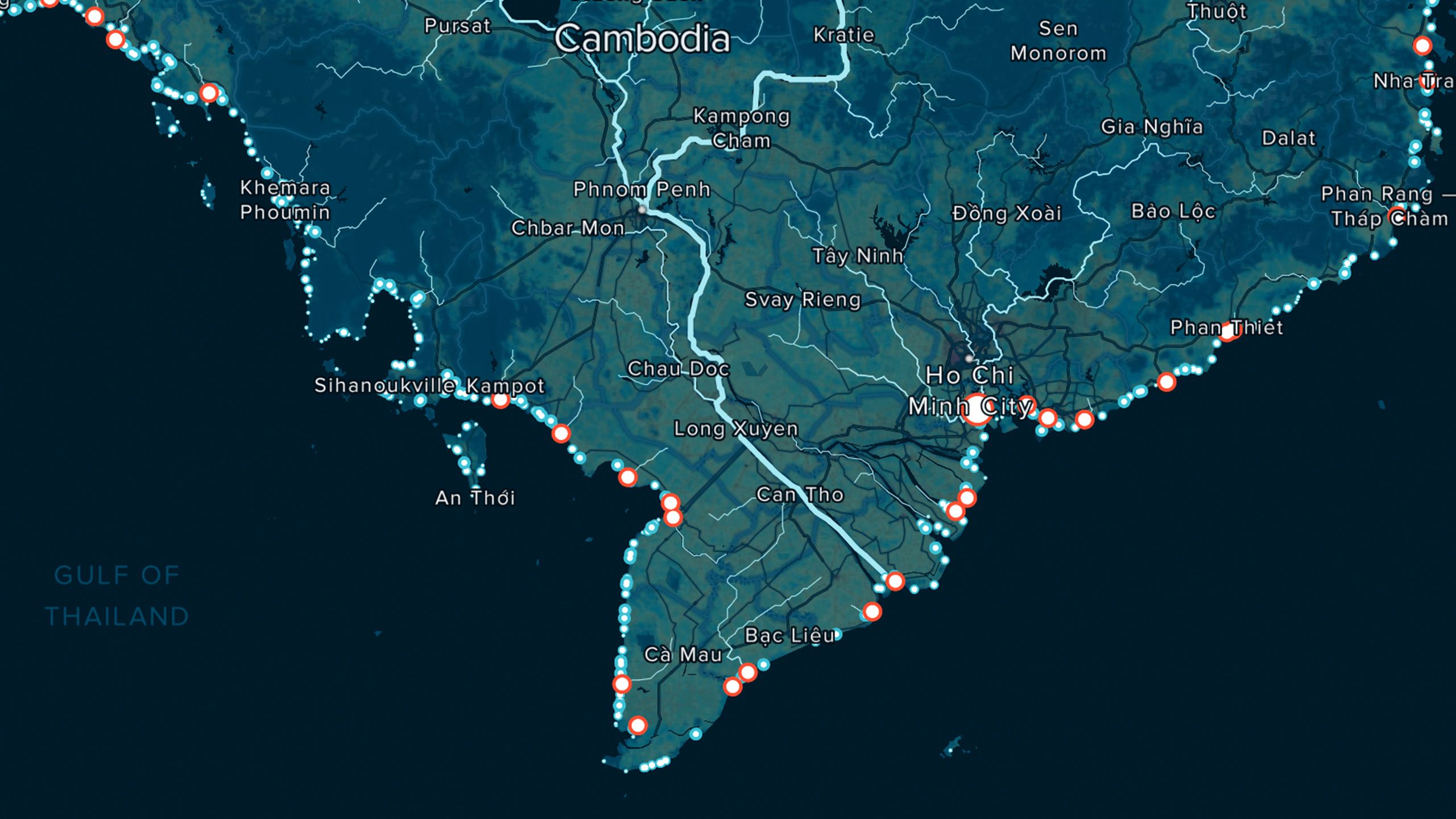

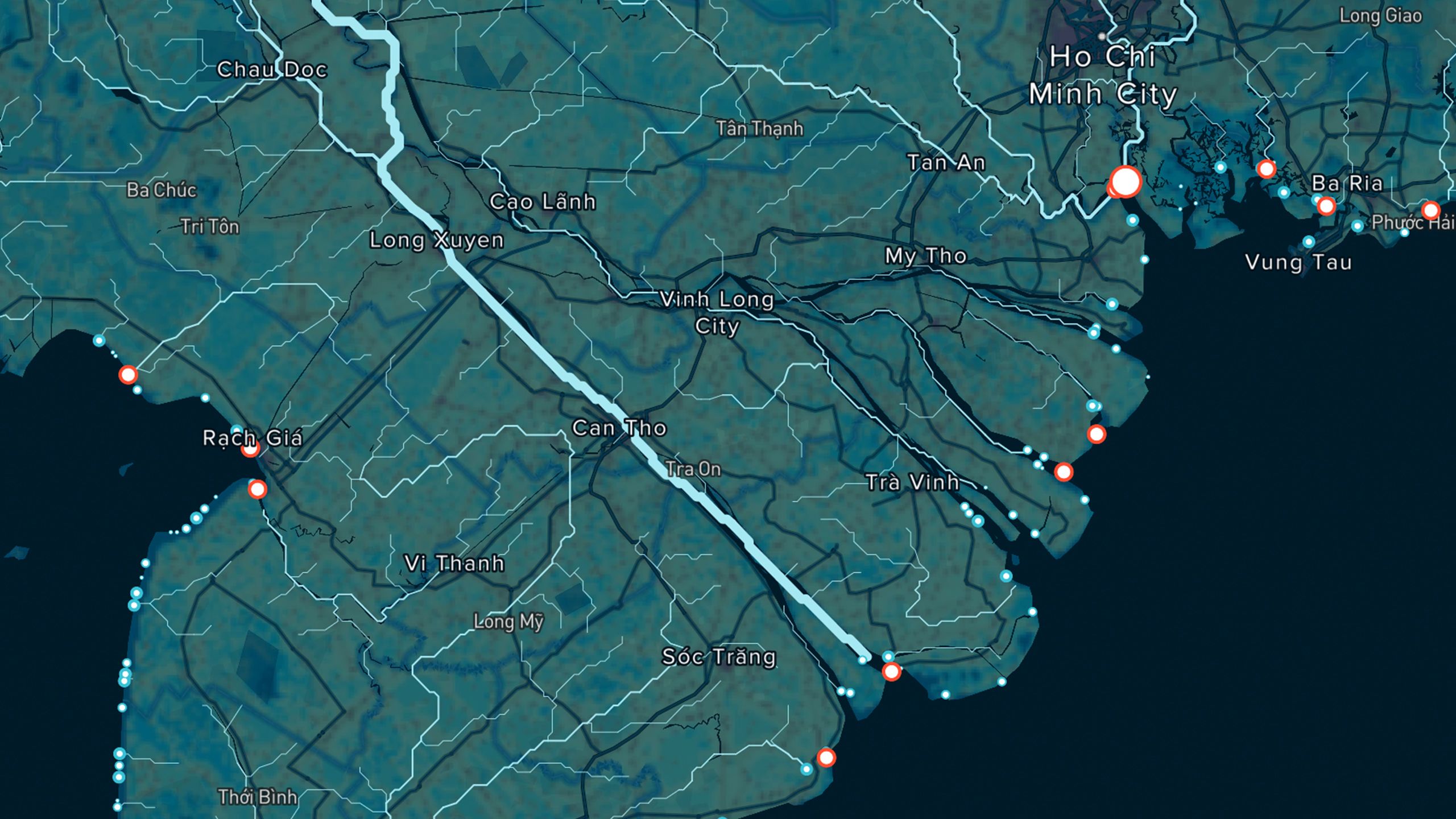

So when it came to deciding where to place its first river Interceptors, The Ocean Cleanup turned to the numbers. Its own analysis found that just 1,000 rivers are accountable for nearly 80% of all river-transported plastic entering the oceans – with small waterways running through dense cities in emerging economies among the most polluting.

The obvious next step is to start with the worst-affected rivers. But it’s not quite so simple. National governments control the rivers within their borders; nothing can be done without their approval.

“That’s where the first challenge starts,” says Rutger de Witt Wijnen, general counsel at The Ocean Cleanup, and responsible for all legal and government affairs involving the cleanup systems. “Which government is responsible for the river? If a river flows through various countries, is it the government where the river enters the ocean, or are others also involved?” Even once this has been clarified, he adds, the team must work out which entities are involved: this could include the national government, the local government, the municipality or the harbour authorities.

De Witt Wijnen’s role is to begin the epic task of stakeholder mapping. Is the river located in an area with willing government support? Is there sufficient waste management infrastructure to handle the plastic being removed from the river? Are there operators who can manage it once it’s in the water? Building a picture of the location and identifying relevant partners is key. It’s about focusing on what The Ocean Cleanup is good at – technology and data – and building partnerships for everything else.

This qualitative data about what’s available or not, combined with quantitative data about the dirtiest rivers, tells the team where to deploy their Interceptor next. “Sometimes you think you’ve found a perfect spot, and it turns out one of those elements is missing. Then you need to move on to the next location,” says De Witt Wijnen.

The Interceptor project was four years in development before officially launching in October 2019. Three Interceptors have been deployed since then: in Indonesia, Malaysia and the Dominican Republic, together gathering almost 250,000kg of waste in just one year. The Ocean Cleanup began its work in Vietnam in 2019 (where it was due to launch before the Dominican Republic) but a combination of complex administrative processes and Covid-19 lockdowns has delayed deployment.

Finally, in November 2021, the Vietnam Interceptor is about to get going.

Boyan Slat came up with the idea for The Ocean Cleanup at just 16 years old while on a diving trip in Greece.

Boyan Slat came up with the idea for The Ocean Cleanup at just 16 years old while on a diving trip in Greece.

The research team processes ocean plastic samples in the laboratory.

The research team processes ocean plastic samples in the laboratory.

The Ocean Cleanup has been researching plastic waste from rivers since 2016, creating an interactive map with detailed information about the world's dirtiest 1,000 rivers.

The Ocean Cleanup has been researching plastic waste from rivers since 2016, creating an interactive map with detailed information about the world's dirtiest 1,000 rivers.

Rutger de Witt Wijnen (left) meeting with the vice chair of the People’s Committee of Can Tho in December 2019 to finalise approval of the project.

Rutger de Witt Wijnen (left) meeting with the vice chair of the People’s Committee of Can Tho in December 2019 to finalise approval of the project.

The first river Interceptor was piloted in the Cengkareng Drain in Jakarta, Indonesia. By 2020, the system was capturing 60% of waste in the river, up to three tonnes a day.

The first river Interceptor was piloted in the Cengkareng Drain in Jakarta, Indonesia. By 2020, the system was capturing 60% of waste in the river, up to three tonnes a day.

RIVER INTERCEPTOR 003: VIETNAM

Vietnam is among the world’s worst culprits when it comes to dumping plastic waste into the ocean. Can Tho City, with a population of 1.7 million, is known for its waterfront lined with floating markets, restaurants, bars and hotels. It’s not difficult to imagine why river waste might be a persistent problem here, and why this site was a high priority for The Ocean Cleanup.

Government buy-in can make or break the project. Vietnam’s national government has made fighting plastic pollution one of its focus areas for environmental policy, and De Witt Wijnen believes that the Can Tho local government is genuinely interested in cleaning up the river. “It wants to be a showcase for the region,” he says.

Government backing is important for another reason. The Ocean Cleanup’s work is funded by philanthropic, commercial and governmental partners; it also makes a small amount of money from recycled plastics, with carbon credits another possible future income stream. But the capital and operating costs for an Interceptor are significant, and so the buy-in of governments in particular is good for long-term sustainability.

“We think that all governments should have skin in the game,” says Witt Wijnen. This doesn’t necessarily mean funding the project in its entirety: Can Tho city authorities have committed to covering some costs after the test phase. Others provide in-kind support – one local government wasn’t able to financially contribute, but lent a ship to the project.

Feet on the ground are key to managing complex relationships between numerous stakeholders. Tan Do, a Can Tho City local with a background in sustainability and waste management, oversees the day-to-day operations and relationships with local partners. This includes officials from the environment ministry – and the local Interceptor operators.

Even with that presence on the ground, cultural differences are unavoidable. Do sometimes finds he is stuck in the middle: working for an international organisation agile in problem solving, in a country that follows stringent procedures and steps. “In Vietnam, the working environment often limits the creativity of the worker,” says Do. “You have to go step-by-step and when you run into a problem, you need to go back a step.” When liaising with multiple government departments and partner organisations, this back-and-forth can become relentless.

Difficulties are doubled because The Ocean Cleanup is working with new technology and unfamiliar systems. It is often a struggle to even transport the parts into the country, because customs works with a pre-agreed list of import goods. “Because it's novel, it's new technology, it didn't fit a box to tick. It’s not a ship, or a vessel, or a pontoon. Everybody could tell me what it is not,” says De Witt Wijnen.

The Interceptor continues to stump local authorities, even once it’s arrived and ready to be assembled, which makes applying for permits a big hurdle. “It’s complex,” says Do. “We have to get the whole system working together.” That system includes representatives from different departments, including the highest government committee in Can Tho City. With no precedent, licences have to be drawn up from scratch – making legal support crucial.

A floating market on the Mekong Delta. Image credit: pxfuel.com

A floating market on the Mekong Delta. Image credit: pxfuel.com

The Ocean Cleanup team in Vietnam oversee the progress of the Interceptor project.

The Ocean Cleanup team in Vietnam oversee the progress of the Interceptor project.

Tan Do has a background in sustainability and waste management and started his own company installing solar panels before landing his 'dream job' with The Ocean Cleanup.

Tan Do has a background in sustainability and waste management and started his own company installing solar panels before landing his 'dream job' with The Ocean Cleanup.

The Ocean Cleanup team in Vietnam.

The Ocean Cleanup team in Vietnam.

The Interceptor project in Can Tho, Vietnam, has had to overcome numerous hurdles including delays due to Covid-19 and difficulty transporting parts into the country.

The Interceptor project in Can Tho, Vietnam, has had to overcome numerous hurdles including delays due to Covid-19 and difficulty transporting parts into the country.

Highly administrative and constantly evolving

The Ocean Cleanup got in touch with international law firm Hogan Lovells in Ho Chi Minh City in early 2018, looking for some assistance with preliminary Interceptor agreements.

Samantha Campbell, partner at Hogan Lovells, was immediately taken by the initiative. Based in Singapore and having worked in Vietnam for nearly a decade, she had seen the pollution in the “extremely vulnerable ecosystem” of the Mekong Delta region. Campbell now leads her firm's work with the nonprofit, and she stresses that the “highly administrative and constantly evolving” legal system in Vietnam needs a tailored approach.

The Ocean Cleanup benefits from the firm’s legal advice on contractual arrangements, licensing and permits in Vietnam. Hogan Lovells also advises on the bespoke contractual arrangements for the manufacture and development of Interceptors in Malaysia for deployment on an ambitious scale globally.

Campbell is particularly impressed with the way the nonprofit is finding new ways to leverage partnerships with manufacturers, donors, corporates and governments to bring Interceptors to the most affected rivers.

“The Ocean Cleanup will have a real and concrete impact on environmental sustainability in some of the most exposed parts of the region,” she says.

It is now all systems go to deploy Interceptor 003. Vietnam is cautiously coming out of lockdown, the Interceptor is in the river, and the team is finalising the last elements before giving the green light.

Once launched, it will go through a test and adapt phase – analysing how well the operations are set up, how efficient it is, how much and what kind of waste it collects. Eventually, The Ocean Cleanup will take a step back and hand over ownership to the Vietnamese authorities.

The nonprofit’s ultimate mission is to be an enabler, bringing together numerous partners in the private and the public sector to develop, finance and deploy Interceptors across the world. It will use insight from its pilot systems to further develop its technology so that it can be efficiently mass produced. The Ocean Cleanup has grand plans – with a goal to remove 90% of plastic waste floating in the oceans by 2040. Interceptor 005 is currently being built in Malaysia, and will be deployed there soon.

Each hurdle the team overcomes is a lesson learned and a step closer to ridding the oceans of plastic. “I’m excited to prove that this system works," says Do. “I wake up every day and I know I’m doing something that is helping my city... Every day is an exciting day.”

All photos courtesy of The Ocean Cleanup

Design by Fanny Blanquier

The Interceptor is soon to launch and begin removing plastic waste from the Mekong River.

The Interceptor is soon to launch and begin removing plastic waste from the Mekong River.

This immersive feature was produced by Pioneers Post in partnership with Hogan Lovells and HL BaSE, the firm’s impact economy practice.

Get in touch if you'd like to tell your story.

J O I N T H E I M P A C T P I O N E E R S

SUPPORT OUR IMPACT JOURNALISM

As a social enterprise ourselves, we’re committed to supporting you with independent, honest and insightful journalism – through good times and bad.

But quality journalism doesn’t come for free – so we need your support!

By becoming a fully paid-up Pioneers Post subscriber, you will help our mission to connect and sustain a growing global network of impact pioneers, on a mission to change the world for good. You will also gain access to our ‘Pioneers Post Impact Library’ – with hundreds of stories, videos and podcasts sharing insights from leading investors, entrepreneurs, philanthropists, innovators and policymakers in the impact space.