Blue forests are under threat. A quiet revolution could save them

Mangroves are among the world’s most valuable ecosystems – essential for local people’s livelihoods and rich in biodiversity. In Madagascar, Blue Ventures has been working with coastal communities to better manage these long-overlooked ‘blue forests’. Will carbon capture be the breakthrough that halts their decline?

Drilling the mud for hours in raging heat, surrounded by swarms of wasps, their feet cut by razor shells: scientists in southwest Madagascar are counting fish and collecting data in the harshest conditions. They are hoping to save one of the most valuable environments on the planet: mangroves.

Those “blue forests”, at the frontier of land and sea, host some of the richest ecosystems on earth. Essential to the livelihoods of coastal communities, they are also extremely powerful carbon traps – storing up to six times more carbon than an equivalent area of the Amazon rainforest.

But they are under threat. Overexploited for timber, charcoal and unrestricted fishing, they are the fastest disappearing forests on earth, at a rate of 1-2% per year. Over the past century, mangrove areas worldwide have declined by an estimated 30 to 50%.

To prevent this, Blue Ventures, a nonprofit organisation that works with coastal communities in more than a dozen countries to protect tropical fisheries, is helping local people to effectively manage their use of mangrove forests. This will be crucial to secure their survival – and success relies on a data-led scientific approach which involves, among other things, counting fish in the mud.

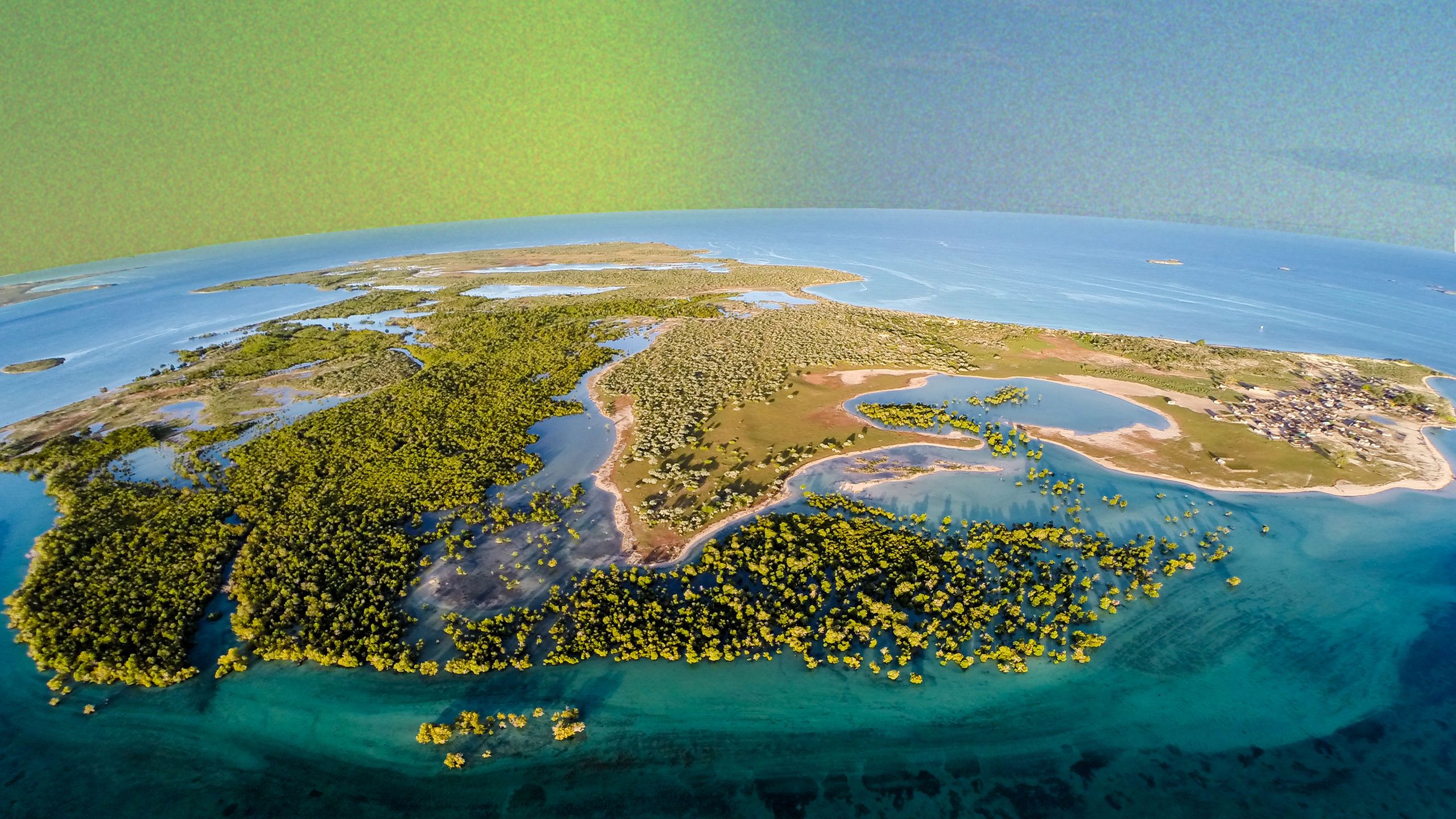

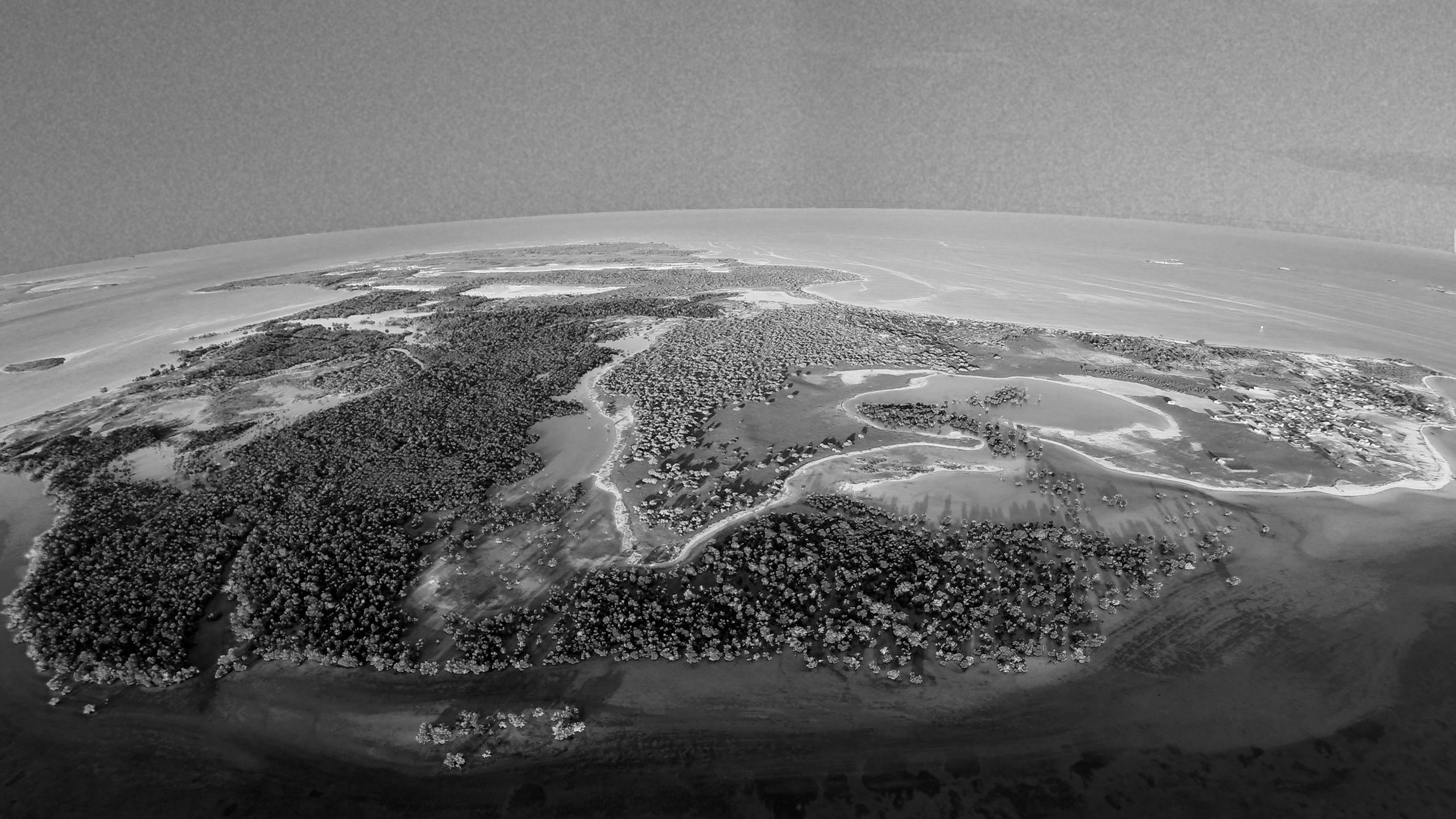

Mangroves host some of the richest ecosystems on earth

Mangroves host some of the richest ecosystems on earth

A woman collects data to monitor the state of the mangrove

A woman collects data to monitor the state of the mangrove

FISH LESS, CATCH MORE

Mangrove conservation is one of the many projects of Blue Ventures, which was founded 20 years ago by Al Harris, a British marine scientist who had the idea of using the revenue from organising diving expeditions to fund marine protection efforts.

As 97% of fish stocks are in developing countries, where small-scale fisheries support the livelihoods of at least 500m people, Harris quickly understood that protecting fisheries wasn’t only about biodiversity. First and foremost, it was a human rights issue: when fish stocks are depleted, the most vulnerable coastal communities lose their only source of subsistence.

So the Blue Ventures approach – now funded by international partners including WWF, UNDP and the Skoll Foundation, as well as its own income from marine expeditions – is not about stopping fishing altogether. “We are very much a pro-fishing organisation,” says Harris, now CEO of Blue Ventures. “We're pro-regenerative fishing that is generally local, that is supporting high value, high quality, nutritious food that's coming from a well-functioning ecosystem and is benefiting the planet and society.”

The nonprofit uses targeted, short-term closures of coastal zones to enable fisheries to regenerate. Once fishing reopens, fisherpeople benefit from increased fish stock and catch more in one go, generating a higher income.

Blue Ventures works with local civil society organisations, such as youth clubs, women's associations or fisherfolk organisations. These are often informal (not legally established), but are “proximate to those communities and credible within those communities,” explains Harris. “They're not operating in the kind of conventional world of philanthropy,” he says. “But they're doing some of the most important work on the planet.”

In small coastal states, there is often little government capacity to monitor and manage small-scale fisheries, and it is very difficult to enforce conservation laws, Harris explains. “In all cases, it’s really about whether the community supports it,” he adds.

Blue Ventures has developed locally managed marine conservation projects in coastal states around the world – and everywhere it faces initial doubt from coastal communities. “There's always scepticism about the trade-off of forgoing fishing,” Harris says. “That's a big concern to any fishing person, anywhere we work. It's about understanding their reality, and coming up with proposals that can limit that upfront cost, that uncertainty, that anxiety.”

The key is to be pragmatic. Asking them to stop fishing or setting unrealistic targets is simply not sustainable, as the livelihoods of many vulnerable coastal communities entirely depend on fishing for their income and food security, Harris explains.

The first step is always to demonstrate the immediate benefits of managing fisheries with data – which can be done quickly as fish stocks are remarkably resilient, Harris adds. In Madagascar, Blue Ventures closed an area to octopus fishing for three months. After the closure period, their data showed that fishermen were getting 90% more octopus in one catch than they did before.

Malagasy fishermen use traditional techniques to catch fish

Malagasy fishermen use traditional techniques to catch fish

Al Harris, founder of Blue Ventures

Al Harris, founder of Blue Ventures

90% of the world's fisheries are either overfished or entirely fished

90% of the world's fisheries are either overfished or entirely fished

Fisheries management enables coastal communities to catch more fish in one go

Fisheries management enables coastal communities to catch more fish in one go

Mangroves: where the land meets the sea

Madagascar has the fourth largest mangrove area in Africa – nearly 2,200km sq, equivalent to 308,000 football pitches, according to Blue Ventures.

Mangroves are intertidal areas where trees grow in seawater – wet half the time, and dry the other half. Full of fish and invertebrates, they are essential to the survival of fisheries as many juvenile species grow there before moving to the sea.

They provide a natural barrier that protects coastal areas from storms, and are valuable fishing grounds for coastal communities, especially women, who fish for mud crabs and shrimps in the shallow waters. Local people also rely on its wood for subsistence.

Like other coastal areas, mangroves are threatened by overfishing. But they face additional pressures, in particular the unregulated harvesting of timber and charcoal sold at local and regional markets. “When you cut down those trees, the fishery collapses,” Harris explains.

BLUE CARBON: A NEW OPPORTUNITY

Malagasy marine scientist Cicelin Rakotomahazo coordinates Blue Ventures’ Tahiry Honko project in southwest Madagascar, a mangrove area of 1,200 hectares that has the potential to store 1,400 tonnes of carbon per year if properly managed. Mangrove management means local communities can still use some of the mangrove resources, but in a controlled way, making it a viable solution that can be sustained in the long term.

The project design is based on a participatory approach. It starts by asking communities what barriers to mangrove conservation they are facing, explains Rakotomahazo, who himself grew up in a coastal community in the north of the island. The communities are also involved in mapping out the different areas for different types of use: controlled exploitation, closure and replantation. Blue Ventures then trains and equips local people to monitor and patrol the mangrove to ensure the community is meeting its targets.

“If you want communities to change, you need to involve people from the start,” Rakotomahazo says.

In parallel to mangrove conservation and restoration work, Blue Ventures helps communities to build alternative income sources, such as aquaculture (seaweed and sea cucumber farming), so their livelihoods depend less on the exploitation of mangroves.

But the conservation of mangroves alone could be a new source of income given its ability to store “blue carbon” – as scientists call the carbon stored in marine ecosystems.

Mangroves are full of growing, flowering plants that photosynthesise and store away carbon. The biggest store of carbon lies in the sediment around the tree – “the smelly oozy mud that you see in those kinds of mangrove forests,” Harris explains.

Cutting down mangroves would release all this carbon into the atmosphere. So Blue Ventures scientists quantified the amount of carbon that could be captured if mangroves are properly managed, and compared this with a “business as usual” scenario where they are destroyed. This figure can be converted into carbon credits – which can be sold on carbon markets. In international carbon markets, the amount of carbon a country can use is limited; if it uses too much, it can buy additional allowances from countries that absorb carbon rather than emit it – these allowances are called carbon credits.

“There's a value on that carbon per tonne, which can technically be verified, audited, and then sold”, Harris explains. “Mangroves offer us all kinds of different opportunities for incentivising conservation, which aren't available in other places.”

For Malagasy coastal communities, the main obstacle to accessing carbon credit money is regulation and legislation. Mangroves are covered by multiple government ministries – those responsible for fisheries, environment and forests – which can sometimes pass conflicting legislation or slow down regulatory reform.

“In Madagascar, defining the beneficiaries of carbon credits is still in its infancy,” says Rakotomahazo. “The question is: who is the owner of this project? The rights of local people should be respected.”

Carbon credits will also incentivise communities to meet targets: if they perform below a certain threshold, that will affect how much money they receive, says Rakotomahazo.

A law is in progress, but Rakotomahazo worries about political instability in Madagascar. “The structure always changes, and sometimes you have to go back to zero,” he says.

And Harris argues that “there needs to be a more equitable marketplace for connecting communities with those [carbon] markets, which currently doesn't exist… The market still fundamentally needs a lot of work to make it connect doers with payers, equitably, and efficiently.”

The Tahiry Honko project is located in southwest Madagascar, off the eastern coast of Africa

The Tahiry Honko project is located in southwest Madagascar, off the eastern coast of Africa

Blue Ventures scientists train community members to collect data in the mangrove

Blue Ventures scientists train community members to collect data in the mangrove

Mangroves host many fish species and invertebrates

Mangroves host many fish species and invertebrates

The Blue Ventures team monitors tree growth

The Blue Ventures team monitors tree growth

A seedling in an area where mangrove replantation is in progress

Seedlings

A mud sample is extracted for data collection

A mud sample is extracted for data collection

A long-running relationship

Blue Ventures was one of the first social enterprises that international law firm Hogan Lovells supported, even before the launch of their HL BaSE practice, which offers low-cost or pro bono support to social enterprises.

Ben Higson, partner at Hogan Lovells, has been accompanying Blue Ventures throughout its journey since 2007. “It sparked my interest in social enterprises,” he says.

Higson, an international corporate lawyer who works mainly on cross-border mergers and acquisitions with big multinational companies, values the fact that his work with Blue Ventures is very different from what he does every day. “I think I've been able to make more of an impact [on their business], because it's a much smaller entity,” he says.

Working with Blue Ventures is also important for Hogan Lovells as a firm because it is an example of how an organisation can make a difference both on a social and environmental level.

Blue Ventures benefits from the firm’s legal advice and services in areas such as corporate structure, intellectual property and employment. Higson says it’s a “real honour” to work with the nonprofit, adding that it is a “success story” that he is proud to have been part of over the years.

ADVOCATES FOR THE MARINE WORLD

Today, Blue Ventures is becoming more vocal about the need for change from governments and consumers in developed countries. “Everything that we've achieved in terms of building local governance is very fragile,” Harris says. Too often, coastal communities see their hard conservation work wasted by industrial trawlers racking the seabed to provide developed countries with cheap exotic products, no matter the time of year.

And climate change “will be terminal for a number of ecosystems that cannot tolerate thermal stress,” explains Harris. “In the tropics, for example, many animals already live at the very upper limit of that thermal tolerance. [Increasing temperature] changes oxygen concentrations in water… So a lot of species will have to move into deeper waters to be able to breathe.” Add this to dying coral reefs, fish migration and food chain disruption, and the future looks bleak for the marine world.

Blue carbon is attracting international attention as a means to reach “net zero” emissions targets. While Harris welcomes the interest, he laments that biodiversity, human rights and food security weren’t enough to make people care about coastal ecosystems. There is some promising legislation in the making, and consumers are starting to pay attention to the ecological – though rarely social – sustainability of what they buy, yet much further action is needed, he adds.

But Harris is encouraged by the rising interest in community ownership of management rights and governance of the sea.

“[It] is the most exciting thing marine conservation has ever, ever had,” he says. “Because it's a civil society movement and a human-led movement. It is a revolution in the way people think about their rights to rebuild fisheries from which they've typically been marginalised.”

Photos courtesy of Blue Ventures

Design by Fanny Blanquier

Traditional net fishing underwater

Traditional net fishing underwater

There is a rising interest in local ownership of marine ecosystems (photo by Martin Muir)

There is a rising interest in local ownership of marine ecosystems. Photo by Martin Muir.

This immersive feature was produced by Pioneers Post in partnership with Hogan Lovells and HL BaSE, the firm’s impact economy practice.

Get in touch if you'd like to tell your story.

J O I N T H E I M P A C T P I O N E E R S

SUPPORT OUR IMPACT JOURNALISM

As a social enterprise ourselves, we’re committed to supporting you with independent, honest and insightful journalism – through good times and bad.

But quality journalism doesn’t come for free – so we need your support!

By becoming a fully paid-up Pioneers Post subscriber, you will help our mission to connect and sustain a growing global network of impact pioneers, on a mission to change the world for good. You will also gain access to our ‘Pioneers Post Impact Library’ – with hundreds of stories, videos and podcasts sharing insights from leading investors, entrepreneurs, philanthropists, innovators and policymakers in the impact space.