All hands on deck

The social enterprise deploying young people to protect our seas

Worsening ocean health, staff shortages in the marine industries, and young people in coastal areas out of work – they all add up to one obvious solution for Sea Ranger Service. The Dutch social enterprise has found a novel way to train up and deploy young people, with the ambitious goal of restoring one million hectares of ocean biodiversity by 2040. Founder Wietse van der Werf tells us how he plans to get there – and why he resisted advice to focus his business on just one issue.

On any given day in the Celtic Sea, you might be lucky enough to see the telltale fin of a blue shark, a pod of dolphins leaping through choppy, bottle-green waters, or a grey seal sunning itself on the rocky coastline. Lying to the west of Wales and south of Ireland, the Celtic Sea is home to diverse marine life and seabirds that live there year round.

A newer addition to these waters is a wind-assisted sailing ship with young trainees on board. These are recruits from an innovative social enterprise called the Sea Ranger Service, the vision of Dutch founder Wietse van der Werf. He’s committed to tackling youth unemployment, and aims to train 20,000 18 to 29-year-olds worldwide to work in jobs related to the sustainable use of ocean resources, also called the blue economy. Their mission is to restore one million hectares of ocean biodiversity by 2040, an ambitious goal to protect the ocean from the triple threat of climate change, pollution and biodiversity loss. Piloted in the Netherlands since 2018, Sea Ranger Service marked its UK debut in January 2024, when it began recruiting in Port Talbot, south Wales.

Previously a marine engineer, van der Werf came to realise that the maritime industry is not only short-staffed but that many port towns and coastal areas in Europe and the UK are blighted by high levels of unemployment, with young people particularly affected. It is not clear exactly how many youth are employed in the blue economy – the International Labour Organization recently estimated that young people make up 13% of those employed in fishing, aquaculture and water transport – but there is consensus on the need to recruit more young applicants, and to ensure they have the skills for emerging industries.

“On the one hand, ocean health is deteriorating and, on the other, we need to create opportunities for coastal youth so that they can transition into the maritime industry where there is a huge need for young talent. These are problems we should be able to tackle,” the founder of the Sea Ranger Service tells Pioneers Post.

The Celtic Sea is home to diverse marine life and seabirds.

The Celtic Sea is home to diverse marine life and seabirds.

There's a big shortage of skills in the maritime industry – while many port towns and coastal areas are blighted by high unemployment. Sea Ranger Service hopes to change this.

There's a big shortage of skills in the maritime industry – while many port towns and coastal areas are blighted by high unemployment. Sea Ranger Service hopes to change this.

Wietse van der Werf, a former marine engineer, says there is a huge need for young talent in marine industries.

Wietse van der Werf, a former marine engineer, says there is a huge need for young talent in marine industries.

What is the blue economy?

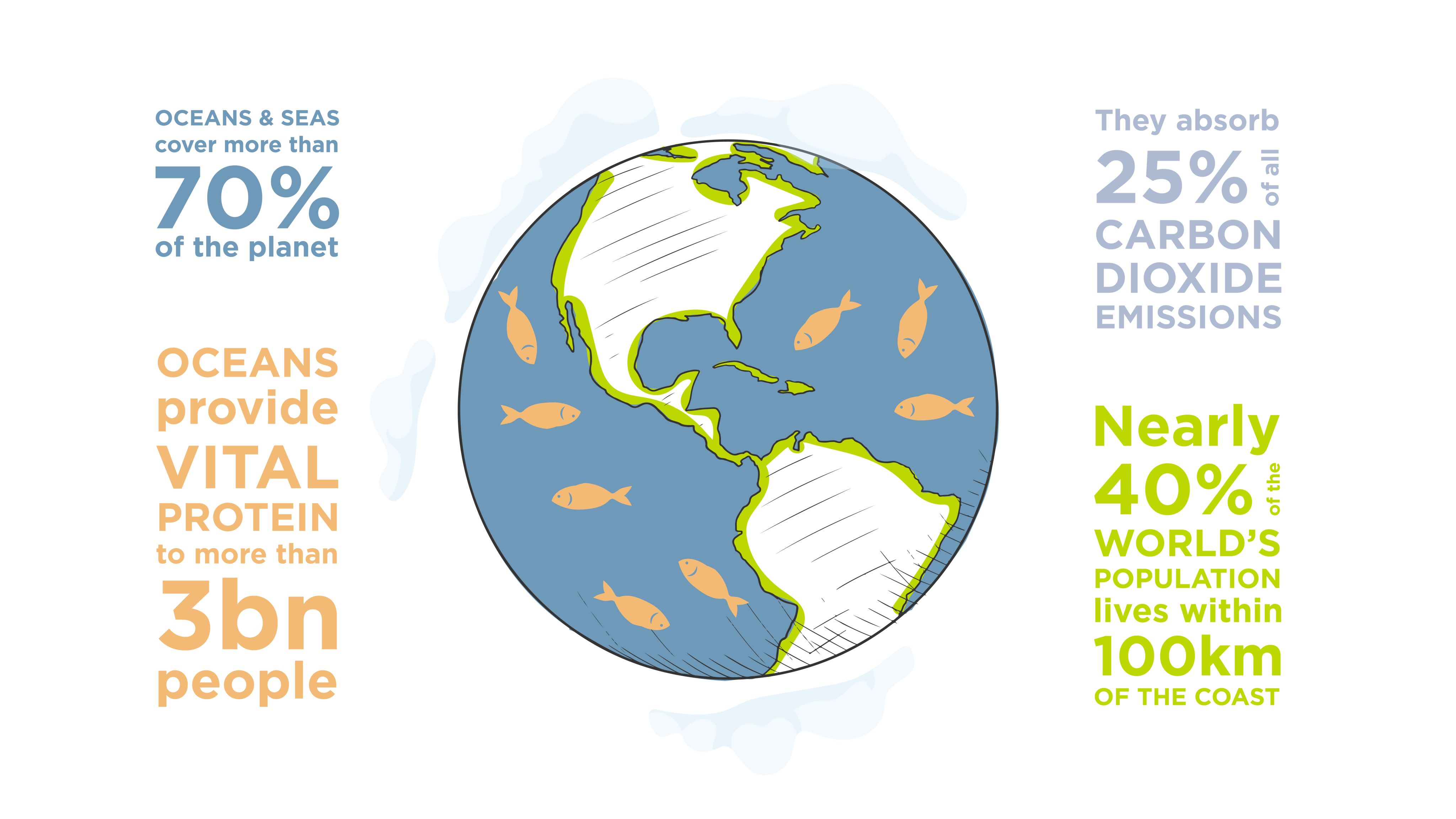

The World Bank defines the blue economy as the “sustainable use of ocean resources to benefit economies, livelihoods and ocean ecosystem health”.

It encompasses activities such as maritime shipping, fishing and aquaculture, coastal tourism, renewable energy, water desalination, undersea cabling, seabed extractive industries and deep sea mining, marine genetic resources, and biotechnology.

The blue economy is estimated to be worth more than US$1.5tn a year, providing over 30m jobs and supplying protein to over 3bn people.

(Source: Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment)

“The ocean is an extraordinary resource that we aren’t currently using – we’re exploiting it, but we’re not managing it correctly.”

Startup solutions

“The ocean is an extraordinary resource that we aren’t currently using – we’re exploiting it, but we’re not managing it correctly.” That’s the assessment of Harry Wright, the founder of Bright Tide, a UK company that helps startups to grow through targeted accelerator programmes. It also works with private sector partners to help them understand and tackle biodiversity loss.

Bright Tide selected the Sea Ranger Service to take part in its first blue economy accelerator programme in 2022. Selected entrepreneurs receive eight weeks of online training and support to get them ready to take on investment. Corporate partners who support the programme with capital, expertise and other resources include global law firm Hogan Lovells, UK property management company The Crown Estate, and consulting business EY.

Wright sees Bright Tide as bridging the gap between the private sector and the innovators who can solve some of the world’s gravest problems. He believes it's “a tricky world” for changemakers and that engaging the private sector is important. “There is only so much grant funding you can apply for or philanthropy available and it’s not a scalable proposition.”

Pursuing profit

Funding is a major problem for social enterprises and it’s a reason many can’t scale quickly enough, or fail altogether. The World Economic Forum estimates that, while the world's 10m social enterprises create 200m jobs and US$2tn in annual revenue, the funding gap is a “significant” $1.1tn. Most social enterprises need patient capital because it can take longer to generate profits; as a result, higher levels of investment from the likes of venture capitalists can be hard to attract, and many rely on one small grant after another.

The Sea Ranger Service has bucked the trend by building a profitable business since its inception in 2016. Initially, most of the money came from impact investors; it also received a €500,000 innovation grant from the Dutch Postcode Lottery in 2020 and in 2023 secured financing from the Triodos Sustainable Finance Foundation, NESEC Ship Finance and PDENH, a Dutch sustainable impact fund. Van Der Werf reckons backers are drawn to the unique business proposition of working in deprived coastal communities. “Many investment funds realised that no one really does something in this space and there’s a real need for these types of ocean solutions,” he says.

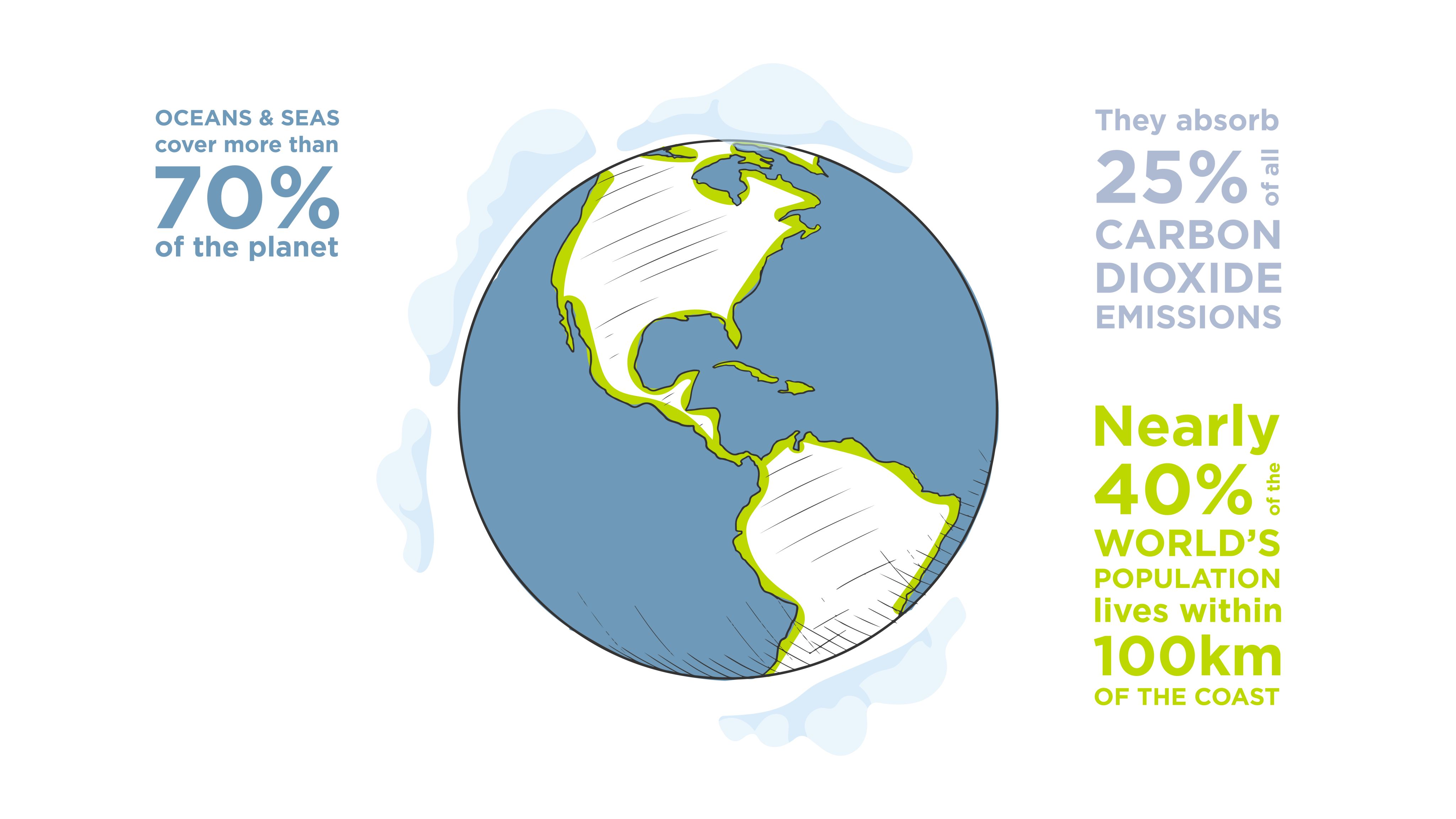

The need is critical, by some estimates. The ocean covers more than 70% of the planet and sequesters half the carbon dioxide on Earth. Nearly 40% of the global population lives within 100km of the coast, many of whom rely on it for their livelihoods. And yet, according to the OECD, sustainable development goal 14 – life below water – is among the least financed of all the SDGs, with an estimated additional US$149bn a year needed for conservation goals.

Harry Wright, a former lawyer who is passionate about conservation, set up Bright Tide to support sustainability startups.

Harry Wright, a former lawyer who is passionate about conservation, set up Bright Tide to support sustainability startups.

Sea Ranger Service has been operating in the Netherlands since 2018. In 2024, it recruited for its first UK bootcamp, in Wales.

Sea Ranger Service has been operating in the Netherlands since 2018. In 2024, it recruited for its first UK bootcamp, in Wales.

Participants at the launch of a Bright Tide programme on regenerative land and sea farming.

Participants at the launch of a Bright Tide programme on regenerative land and sea farming.

Sustainable development goal 14, which encompasses life below water, is the least financed of all the SDGs.

Sustainable development goal 14, which encompasses life below water, is the least financed of all the SDGs.

Protecting the planet’s largest ecosystem

Yet SDG14 (‘life below water’)

faces a financing gap of

US$149bn a year

Sources: United Nations, OECD

Replicating what works

Since 2018, the Sea Ranger Service has serviced 17 government contracts for conservation work, 15 of which had never before been contracted to an external party, according to van der Werf. “These contracts are big and there aren’t really many startups doing it because the capital investment needed to have a ship at sea is high,” he says. The sailing vessel allows the enterprise to take on offshore work, bringing in enough revenue to run the social programmes.

One of these contracts is to do marine mammal observations in the Celtic Sea for The Crown Estate, a UK landowner that manages some of the seabed and coastline around England, Wales and Northern Ireland. This type of work is usually only done by a handful of larger maritime companies – and van der Werf says they're the only social enterprise currently contracted to do it there. This type of work has been so successful, in fact, that the enterprise is building a second sailing ship, to be completed later this year.

To scale further the business is expanding, through a social franchising programme that would replicate the Sea Ranger Service business model in other countries. It’s actively looking for entrepreneurs in France and the UK, building on the bootcamps that have already been run there, with Spain the next target. The business model lends itself to franchising, van der Werf explains, because it would take years of development to start from scratch but they’re offering successful applicants an out-of-the-box solution.

What is social franchising?

Social franchising is a method of expansion for social enterprises. It works in a similar way to commercial franchising and enables the organisation to scale and expand the reach of operations, and provide the same services in new markets and locations, working with a local social franchisee partner. Social franchising allows both parties flexibility within their role in the franchise model, while also ensuring the goals, brand and resources from the parent company are fully realised by the franchisees.

Source: Franchise Company

Importantly, the founder adds, they are financially sustainable. Turnover in 2023 was €1.1m, and for 2024 is expected to be €2.5m. Fast-forward 10 or 15 years, and he foresees “all sorts of capacity building, we are building infrastructure, we are restoring and managing oceans at scale without any philanthropic funds”.

Wright from Bright Tide believes social finance has to be leveraged more effectively to support the blue economy. “Organisations like UnLtd and Better Society Capital do a commendable job in backing entrepreneurs tackling social issues such as homelessness and economic inequality,” he observes. “However, there is an increasing need for social finance to also support entrepreneurs working on climate and biodiversity initiatives.” Those he meets through Bright Tide need flexible financing with favourable interest rates, supplemented by grants and revenue participation agreements. These types of terms are not easily secured through conventional providers.

For Sea Ranger Service, one of the bigger challenges while developing an initial business strategy was in fact pushing back on some of his pro bono advisers, who thought the business needed more focus. They asked van der Werf to choose: did he want to train young people, did he want a government contract, to build ships, or to restore nature? “I detested that,” he says. “I thought the strength is that this comes together.” He says a turning point was when he got the navy, an important stakeholder, on board – a development that caused others to take note.

Sea Ranger Service aims to train 20,000 young people by 2040 in areas including marine surveying and nature conservation.

Sea Ranger Service aims to train 20,000 young people by 2040 in areas including marine surveying and nature conservation.

The social enterprise has secured financing for a second ship, which will be used for conservation work.

The social enterprise has secured financing for a second ship, which will be used for conservation work.

Another business supported by Bright Tide is SafetyNet Technologies, a precision fishing startup.

Another business supported by Bright Tide is SafetyNet Technologies, a precision fishing startup.

“The Hogan Lovells team helped to produce an initial term sheet to be shared with Sea Ranger Service's debt investors and a template loan agreement to facilitate that debt investment, as well as assisting in negotiations with lenders. We’re really pleased to have played a small part in the development of such a fantastic social enterprise.”

Young people at the helm

Apart from the offshore work, one current project at Sea Ranger Service is planting seagrass – some species of which can sequester 30 times more carbon per hectare than a forest – in 13 locations in the Eastern Scheldt estuary in the south of The Netherlands. Another project in the Wadden Sea, headed up by the science lead who also guides Sea Rangers, has more than tripled seagrass restoration, from 350 hectares a few years ago to over 1,200 today. “That’s the largest successful intertidal seagrass restoration in the world,” reports van der Werf.

And it’s young people who are doing the work, with no extensive training required. Selected Sea Rangers go through a nine-day bootcamp run by navy officers and other professionals. As soon as they finish they are paid a living wage for a contract to work full time for between six months and a year. Some work on restoration projects, while others are trained as drone pilots and others go out to sea.

Overall, Sea Ranger Service has employed 172 young people, and half of them have gone on to get jobs in the maritime industry. It’s also addressing the traditional gender imbalance in this industry. While women represent only 1.2% of seafarers globally, a striking 72% of the 1,000 applicants to the Sea Ranger Service so far have been women – which van der Werf says is a testament to making this line of work more attractive and safer than is usually the case.

Twenty-year-old Ted Artingstall is from Devon in the UK. He’s never had a job before but is spending some of his summer before finishing his university degree working as one of eight Sea Rangers on its ship in the Celtic Sea. He agrees that unemployment is a problem for young people in his area. “We are a seafaring nation, lots of young people should be eager to get stuck into sailing like this, but there aren’t many opportunities,” he tells Pioneers Post from aboard the ship.

Artingstall is currently monitoring marine wildlife and says he feels very lucky to be learning things that can't be taught in a classroom. He says he will never forget the first time they went out to sea and he felt the power of raising the mainsail in his hands. He’s now hoping to forge a career in an ocean-related field.

Van der Werf is most proud of training the next generation of maritime professionals and making the sea an exciting prospect once more. “Many young people feel they are left behind and that they don’t play a part. Disenfranchising, I think, is a real danger. We need active, productive, happy citizens who feel they have a role to play in the world.”

Some species of seagrass can sequester 30 times more carbon per hectare than a forest, so restoration of these areas is vital.

Some species of seagrass can sequester 30 times more carbon per hectare than a forest, so restoration of these areas is vital.

Sea Rangers must complete a nine-day bootcamp run by navy officers and other professionals. When they finish, they get a full-time, paid contract of up to a year.

Sea Rangers must complete a nine-day bootcamp run by navy officers and other professionals. When they finish, they get a full-time, paid contract of up to a year.

“We are a seafaring nation, lots of young people should be eager to get stuck into sailing like this” - Ted Artingstall, from Devon in southwest England.

“We are a seafaring nation, lots of young people should be eager to get stuck into sailing like this” - Ted Artingstall, from Devon in southwest England.

Three more organisations creating opportunities for young conservationists

Wildbound

Founded in 2017, the Beijing-based organisation is supporting young climate activists in China with the resources they need to make a difference. Chief impact officer Faye Lu envisions it as a “decentralised network” that takes some inspiration from Eastern cultures. “Protecting the Earth is not just about calculating carbon or protecting one species, but actually being connected to nature,” she says.

The Crown Estate

With a £16bn portfolio, this national landowner in the UK manages the seabed and some of the coastline. It has been running marine internship programmes for nine years and has worked with 45 young people in England and Wales. Many of them have gone on to secure jobs in the marine industry, including with energy company Orsted and the Wildlife Trusts.

Force of Nature

A global community of 16 to 35-year-olds, the platform offers training and workshops, as well as volunteer and paid opportunities through its network. It also has climate cafés in 49 countries – places where young people can meet and have open conversations about taking action on environmental issues.

“On the one hand, ocean health is deteriorating and, on the other, we need to create opportunities for coastal youth so that they can transition into the maritime industry where there is a huge need for young talent. These are problems we should be able to tackle.”

Image credits: Sea Ranger Service; wirestock/Freepik; Forest_Wolf/Pixabay; Harry Wright; urtimud.89/Pexels; Bright Tide; Francesco Ungaro/Pexels; kichigin/Freepik; SafetyNet Technologies; Flensshot/Pixabay; Luciann Photography/Pexels.

Written by Carla Parks; design by Fanny Blanquier; editing by Anna Patton.

This immersive feature was produced by Pioneers Post in partnership with Hogan Lovells and HL BaSE, the firm’s impact economy practice.

Get in touch if you'd like to tell your story.

J O I N T H E I M P A C T P I O N E E R S

SUPPORT OUR IMPACT JOURNALISM

As a social enterprise ourselves, we’re committed to supporting you with independent, honest and insightful journalism – through good times and bad.

But quality journalism doesn’t come for free – so we need your support!

By becoming a fully paid-up Pioneers Post subscriber, you will help our mission to connect and sustain a growing global network of impact pioneers, on a mission to change the world for good. You will also gain access to our ‘Pioneers Post Impact Library’ – with hundreds of stories, videos and podcasts sharing insights from leading investors, entrepreneurs, philanthropists, innovators and policymakers in the impact space.