Staying at home, fleeing from home: are we now all grieving for our former lives?

Around the world today, there are almost 26 million refugees and another 41 million people displaced within their own country, according to the International Organisation for Migration.

In response to the Covid-19 crisis, many countries, including Portugal, France, and the UK, are granting temporary residency rights, access to healthcare and social security to immigrants and asylum seekers whose application is still being processed.

This provides them some short-term security. But with an international tightening of borders and travel restrictions, on 10 March resettlement travel for refugees was globally suspended. This will put many people in danger across the world.

For those that have already begun to establish new futures in new places, many have lived through painful experiences. Social ventures play a critical role in working to support these individuals and the communities they live in.

Among those is Migrateful, a London-based social enterprise that supports the integration of refugees and migrants into the community through cookery courses. In this very personal story, founder Jess Thompson – now recovering after recently being hospitalised with the coronavirus – reveals how her own fears, and her sense of powerlessness, were brought into sharp relief through conversations with some of the chefs she works with.

Jess Thompson

Founder of Migrateful

Last Saturday I took myself to A&E because I was finding it hard to breathe. The doctor told me that I had the coronavirus. I had spent the last two weeks reading about how people with long term conditions such as diabetes had a much higher risk of dying from the virus. I have type 1 diabetes. So, there I was lying in my hospital bed, convinced that I was going to die.

I didn’t die. On reflection, the reason I couldn’t breathe was probably partly because I was panicking so much about the prospect of dying. Understandable perhaps; this coronavirus pandemic is terrifying. As I’m writing this article [30 March], many people are dying because of it. Never before, in my lifetime, have we had to deal with the fear of an invisible enemy killing our loved ones.

Leaders across the world are declaring war. Boris Johnson insists ‘we must act like any wartime government and do whatever it takes’. While Donald Trump announced that this is ‘our big war’.

I have never experienced a war before. But many of the Migrateful chefs have. Until now, when I heard their stories of war and fear, they felt so removed from my own life. When I first met Majeda, one of the Migrateful Syrian chefs, she said she was in a constant state of grief because of the number of people who were dying in her country. Since 2006, 586,100 people have died in the Syrian civil war. To put this into perspective, at the time of writing this article, so far, 34,017 people have died globally from the coronavirus and 1,228 have died in the UK.

A few days before going to hospital, I took the difficult decision to cancel all Migrateful cookery classes for the foreseeable future to protect our chefs and customers from the coronavirus outbreak. Migrateful is the social enterprise I founded almost three years ago which supports refugees to teach their traditional cuisines to the public. We have 32 chefs from around the world teaching 20 cookery classes a week (pre-coronavirus). Most of our income (85%) comes from cooking class sales, so overnight our income stream dried up. I felt incredibly anxious, unsure about how Migrateful could financially survive this crisis — we only have around two months’ worth of financial reserves and The Guardian predicted that the pandemic will last 12 months.

The day after returning from the hospital, my mum told me that my grandfather has cancer all over his body and doesn’t have long to live. This news was a huge blow. I love my grandfather dearly and the idea of not being able to say goodbye to him before he dies (because I needed to self-isolate) was too much to bear. After hearing this, I spent most of the afternoon crying. Everything felt out of my control, all sense of normality and security gone. I said to my housemate: “I just want my normal life back”.

My worries were put into perspective the next day when I called the Migrateful chefs. They had seen war, felt grief, been crippled by loss — more so than most of us can comprehend. But they persisted. The thought: ‘I just want my normal life back’, was one they had been enduring for years. Calling Betty, Majeda and Ahmed that morning left me feeling inspired and uplifted by their ability to deal with life’s challenges. At this time, when we are all facing fear and uncertainty, and perhaps grieving for our former lives, I thought we could benefit from their wisdom.

Betty was trafficked to the UK when she was 16. She had to wait 19 years before she was given immigration status. During those years she couldn’t work nor could she receive benefits. She told me:

"When I don’t have control of what’s happening in my life, I try to work out the little things that I do have control over.

Credit: Federico Rivas

Credit: Federico Rivas

Every day I had to deal with the uncertainty of not knowing when the Home Office would let my life start. Many times, I felt overwhelmed, like my brain was an overloaded computer screen with too many tabs open. I had to find ways of closing down each tab. I find watching a film really helps me to do this, or listening to music.

Whenever there was a drought in Nigeria, my father told me not to panic because the rain will come again, and it always did. This is the most important lesson my father taught me: when bad things happen (like when my mum passed away), be patient and wait for the pain to pass.

Throughout my life, I’ve never lost my sense of hope. I believe that everything happens for a reason."

When speaking with Majeda on the phone, she said to me:

"This coronavirus outbreak reminds me of when the war broke out in Syria. It feels like a dream, having to get used to a new way of life, full of fear. I remember the day the Americans first said they would attack Syria. Everyone was panic buying, the shops were left empty like they are here now.

I remember going into the areas in Syria which were under attack to help feed civilians who had no food (that’s what the government later imprisoned me for). We had to hide underground for hours with the sound of bombing overhead — it was very scary.

In times of uncertainty, I try to focus on the things I can be grateful for.

Right now, I feel so grateful to be here in the UK. Where there is a good health service, state benefits to support those who have had their income stream cut off, and where the government is keeping people informed. In Syria, we have none of this. Our health service has been destroyed by the war. Since 2011, 5.6 million people have fled Syria. The majority are currently living in refugee camps. I am scared that when the virus reaches the camps, the death toll will be unimaginable, due to poor sanitation and everyone living so closely together in tents. I know I am so lucky to be a refugee here in the UK. Although I am worried about my husband. He’s stuck in Syria because they’ve closed the border. He was meant to fly to the UK in April to finally be with me and our two sons."

Ahmed was shot in Lebanon and paralysed from the waist down and now has to use a wheelchair. He explains that you learn about who you really are when you lose everything.

Credit: Federico Rivas

Credit: Federico Rivas

"I had a great job in Lebanon. I had my fiancée, my family and friends. A beautiful house. Then one day, I lost everything: my ability to walk, my ability to work and my ability to live safely in the country that I love."

Due to the coronavirus crisis, not only has Ahmed’s court case with the Home Office been postponed (four years after arriving to the UK he’s still waiting to be granted asylum), but, on top of this, the high-risk operation he was due to have last week, to reduce the acute pain he experiences from the gun wound, has also been postponed. He said:

"For me, the best way to cope when everything is out of my control is to try to surrender to the sadness and uncertainty, instead of trying to run away from it. When you really face it, it can’t hurt you any more.

Getting paralysed and losing everything taught me that life has many different stages. One moment you’re up and in the blink of your eye you’re down. But you must never give up. Every stage involves a new version of you. There’s always a light at the end of the tunnel.

I believe life makes these things happen for a reason, only time shows you the reason why.

I feel very grateful for my life. I know that I’m still better off than a lot of other people."

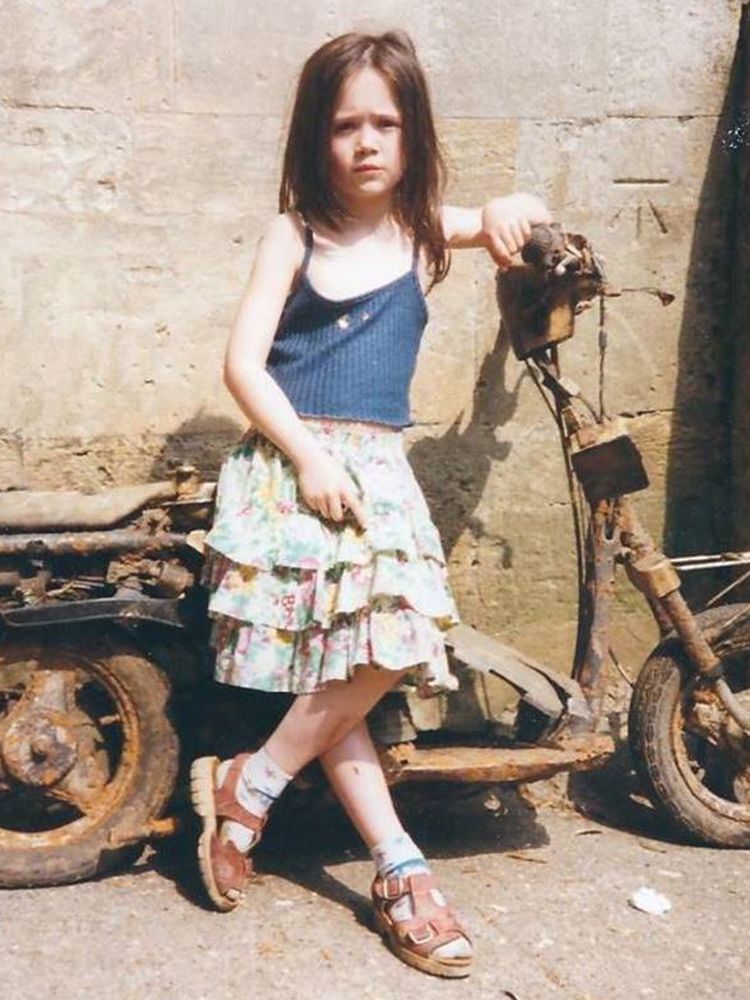

These recordings are from a Migrateful chef who remains anonymous for safety reasons.

After leaving her abusive husband, she was the victim of an attempted honour killing by her family. She compares the coronavirus quarantine to her situation of waiting to get her immigration status from the Home Office for all these years.

My lessons

After my phone conversations with Betty, Majeda and Ahmed, I no longer felt like crying. I sat calmly, humbled by their strength and wisdom. I have learned to focus on:

What I can control right now

For example, the Migrateful crowdfunding campaign is going well and we are piloting getting the chefs to teach online cookery classes as a potential revenue stream.

Gratitude

I have been FaceTiming my grandfather every day since I heard the news about his cancer. He is so cute.

I saw a beautiful act of devotion from my best friend, Emily; risking her life in a COVID-filled hospital to sit at the bottom of my hospital bed, quietly knitting, to keep me company in my time of crisis.

Surrendering

Accepting that we don’t have control over this situation. We don’t know when it will end. And that’s OK. Maybe everything does happen for a reason. Maybe this break will give me a chance to get some much-needed rest and improve the Migrateful systems before resuming activity.

I reminded myself that this was not the first time that a challenging and unexpected ‘new normal’ was thrown into my path. I was 11 years old when I was diagnosed with diabetes. I remember feeling like all my freedom had been taken from me; suddenly being forced to take daily insulin injections and dealing with difficult blood sugar fluctuations. The hardest part was being told that this illness would be with me for life, and if I didn’t get better at controlling my blood sugars, I’d soon be blind. I cried every day when I got this diagnosis, until one day I woke up and realised, no matter how much I cried, it wasn’t going to go away. And from that day on I stopped crying. The amazing thing about humans is our ability to adapt.

Hope

The coronavirus can infect us no matter our race, our religion, our politics or our social class. Many of us are now relying on government benefits to financially survive and on the NHS to stay alive. This experience reminds us that we, humans, can all be vulnerable and when we’re vulnerable it’s OK to need help. I hope that in the post-coronavirus world, this realisation compels us to meet our duty of care when we hear stories about refugees being forced to leave their homes for reasons out of their control.

With thanks to Jess Thompson for the interviews, photos and audio.

This story is the first of a new style of multi-media, or ‘immersive’, features we are producing on Pioneers Post.

Get in touch if you'd like to tell your story.

Thanks for reading our stories. We're working hard to provide the most up-to-date news and resources to help social businesses and impact investors share their experiences and get through the Covid-19 crisis. But we need your support to continue. As a social enterprise ourselves, we rely on paid subscriptions and partnerships to sustain our purpose-led journalism – so if you think it's worth having an independent, mission-driven, specialist media platform to share your news, insight and debate across the global impact movement, please consider subscribing.