Managing an oxymoron: navigating the thin line between connection and independence at Trafigura Foundation

The mission of a corporate foundation may be very clear. But because it is related to a for-profit commercial company, navigating the fine line between using the business’s resources to maximise impact and keeping enough distance to avoid commercial influence can be challenging. The Trafigura Foundation provides an example of how to stay independent, yet connected: at its heart is a very clear position on purpose – that includes open conversations, clear communications, and knowing when to say no.

Running a corporate foundation is not always easy. The mission to achieve social or environmental impact – for example, by investing in social enterprises – may be very clear. But the work can be made more complex because they are related to a commercial company, often big and affluent. Some corporate foundations will be closely intertwined with the business, as is the case of Ikea Social Entrepreneurship, the furniture brand’s social investor. But others prefer to keep their distance.

Because when it comes to doing social good, a corporate foundation’s decisions need to be made primarily with impact in mind. If it is under pressure from its related business to make decisions that aim to benefit the business, the foundation is at risk of drifting away from its original purpose. This is what EVPA researchers call a risk to “impact integrity”.

Read more in this series: Flat-packed social purpose: how Ikea’s ‘impact integrity’ clicks into place

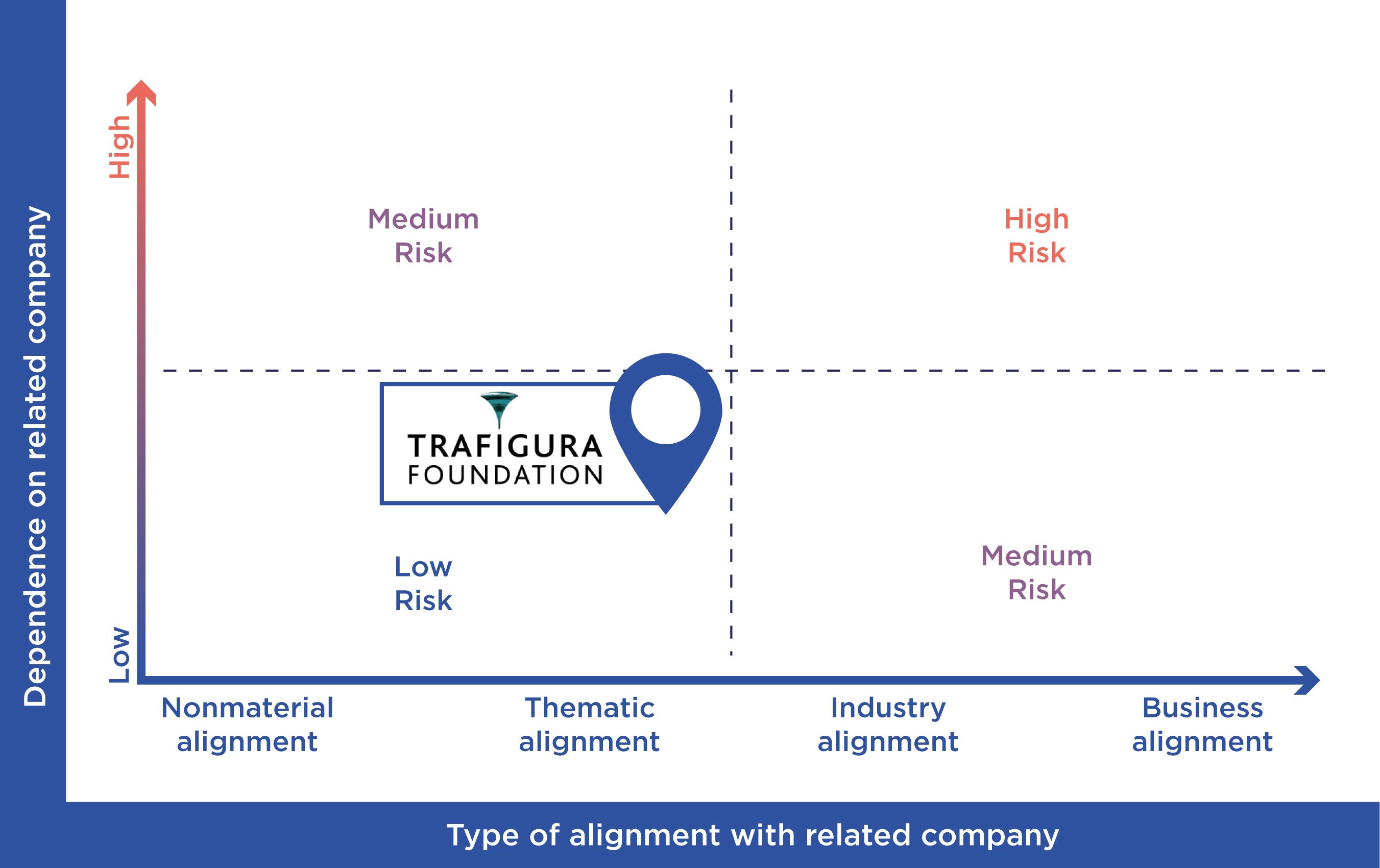

So how to ensure corporate foundations stay true to their mission? In a study published earlier this year, EVPA researchers looked at how to mitigate risks to impact integrity according to the type of relationship corporate social investors have with their related business.

Among the corporate social investors deemed at “low risk” to impact integrity by the researchers is the Trafigura Foundation. The foundation was created by Trafigura, one of the world’s largest companies in the commodity trading industry – an industry that is very carbon-intensive. It is also, as EVPA puts it, “often subject to controversies due to labour practices in areas such as mining, resulting from the high complexity of the supply chains in the sector”. As a result, commodity trading companies are more likely than many other firms to be met with negative perceptions from the public.

Low risk therefore doesn’t come without effort: it involves navigating a tightrope between independence and connection, insisting on open conversations – and knowing when to say no.

Almost an oxymoron

The Trafigura Foundation was established in 2007 as an independent body, working on issues at arm’s length from the commodity-trading company. Its purpose is purely philanthropic, Vincent Faber, its CEO, explains: a means of “giving back to society” by supporting activities undertaken by charities and other NGOs, independently from any business considerations. “It was never seen as a vehicle for corporate social responsibility,” he says.

The foundation’s mission is to improve the livelihoods of vulnerable communities around the world, and it focuses on two areas: fair and sustainable employment, and clean and safe supply chains. It also supports Trafigura employees to volunteer for charitable causes that matter to them.

The foundation receives all of its funding from Trafigura, in the form of long-term commitments (on a four-year rolling basis), but the company has no influence on how the money – some $7.7m in 2021 – should be used.

“Our main driver is impact,” says Faber, adding that the foundation’s goal is “to serve the beneficiaries, not to serve the business”.

But the relationship between the Trafigura Foundation and its related company is not so black and white. “It's very subtle and sometimes a little bit complicated,” says Faber, who has been heading the foundation since its creation. “We are clearly independent in what we do, how we do it and why we do it – yet connected.”

The foundation’s board is made up of a blend of people with and without a background in the company. Some trustees are company executives, some are involved with the company but have non-executive, supervisory roles, and others have no connection to the company at all – a “fair representation” of the independent yet connected relationship, Faber argues.

At first, the foundation operated in sectors completely independent from the company’s area of work. But over the years, the foundation aligned some of its activities with sectors more relevant to Trafigura. For one simple reason: this would enable the foundation to maximise its impact. By leveraging the company’s expertise, knowledge and networks in certain industries, the foundation could provide precious added value to investees, beyond the funding – a setup that EVPA calls industry alignment.

This situation created a tension, however, that the foundation has to navigate: moving closer to the company to maximise its impact through a stronger strategic alignment with the industry in which the company operates, but keeping enough distance to stay true to its mission. “This is also almost an oxymoron – and managing an oxymoron is not easy,” says Faber.

Education for Employment, a Trafigura Foundation investee, provides skills training for disadvantaged youth in Egypt.

Education for Employment, a Trafigura Foundation investee, provides skills training for disadvantaged youth in Egypt.

Planet Indonesia, a Trafigura Foundation grantee, supports the economic needs of rural communities through conservation of the local ecosystem.

Planet Indonesia, a Trafigura Foundation grantee, supports the economic needs of rural communities through conservation of the local ecosystem.

Vincent Faber, CEO, Trafigura Foundation.

Vincent Faber, CEO, Trafigura Foundation.

Glossary

Corporate social investor

A legal or organisational structure related to a company (by name, funding, structure and/or governance), with the primary intention of creating social impact. These may be corporate foundations, impact funds, accelerators or social businesses, for example.

Impact integrity

Adherence to an organisation’s social mission, regardless of (negative) external influence – in particular from its related company due to its commercial agenda.

Strategic alignment

When a foundation or other corporate social investor works in a sector, industry, geography or business area overlapping with the one in which its related company operates, so it can leverage the company’s assets and expertise to maximise its impact.

“We are clearly independent in what we do, how we do it and why we do it – yet connected”

Outside the fence

“The main risk is mission drift,” says Faber: if the foundation deviates from its original purpose by giving too much pre-eminence to Trafigura’s business considerations. “That's where the whole notion of impact integrity takes all its essence.”

To manage the influence of the company, it’s vital to clarify what the role of the foundation is, and what it isn’t. “We have to be very transparent with our corporate colleagues on the reasons behind our actions,” says Faber. “Sometimes we cannot engage, because the line is too blurred or the risk of being seen as serving the corporate interests rather than serving the beneficiaries is too high.”

It isn’t the foundation’s job, for example, to solve problems resulting from the company’s activities. Faber is adamant: if a company, in whichever field of activity, wants to compensate for the negative impact intrinsically linked to the nature of its operations, it must do so under a CSR policy (and budget). Not under a philanthropic one. This is how Faber sees the role of the Trafigura Foundation.

At times, the foundation has had to meet the company’s proposals with a flat “no”, as when it was asked to finance a survey on the environmental impact of a port infrastructure in Brazil. “Even though the proposed operation was the right thing to do, the key question was whether the foundation is the right actor to fund that particular project,” Faber says.

His answer was clearly no. “If the purpose is to address corporate issues, to foster good relationships with surrounding communities, or to secure a licence to operate, then things should happen under a CSR budget, not through the foundation.”

On another occasion, Trafigura wanted to work with an NGO to improve the labour conditions in small-scale or artisanal mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where the firm was involved.

At the time, artisanal mining in DRC was a sort of wild west, “Gold-Rush style” industry, with “child labour, community issues, violence, you name it”, says Faber. Trafigura wanted to support initiatives to encourage miners’ cooperatives to adopt lawful and ethical practices and to improve their working conditions and living standards.

The project would, of course, benefit local communities, but also the business. The foundation turned it down, as the action had part of its focus on Trafigura and its partners’ supply chain workers, rather than on the surrounding communities at large. It was clear to all that these activities had to be initiated within a specific Trafigura responsible sourcing initiative.

But the foundation did fund projects to support the same communities, in a more peripheral way, focusing on livelihoods, education and women’s empowerment, for example. Because the company and foundation were operating so close to each other, it was necessary to clearly distinguish “the corporate dimension – including in its community-oriented component – and the philanthropic, community-driven dimension”, says Faber. The foundation calls the former “inside the fence” – inside the boundaries of corporate activity – and the latter “outside the fence” – beyond corporate boundaries, where the foundation can operate in its own right and faithfully according to its mission.

The foundation’s activities may interact with Trafigura’s operations, but only at an industry-wide level. For example, the foundation sometimes funds projects – such as ISWAN, below – that relate to the commodity trading industry as a whole.

Sticking to this clear position and being transparent about it is at the heart of managing the relationship with the company, Faber says – even if it doesn't always make for easy conversations with his corporate counterparts. “It’s a healthy, rough conversation,” Faber says, “as would happen between the different departments of a company”.

ISWAN provides a 24h-helpline to support seafarers’ wellbeing. Credit: Noel Agustin Gabrido.

ISWAN provides a 24h-helpline to support seafarers’ wellbeing. Credit: Noel Agustin Gabrido.

Education for Employment.

Education for Employment.

ISWAN: “We always felt unrestrained”

Founded in 2013, the International Seafarers’ Welfare and Assistance Network (ISWAN) is a membership organisation that promotes and supports the welfare of seafarers around the world. It is mostly known for its 24-hour helpline that provides direct support to seafarers in 10 languages – on issues from healthy eating to suicide prevention – and distributes a hardship fund for seafarers among other projects.

The charity, which has a yearly budget around £1m, is mostly funded by grants from foundations, but also by revenue from membership fees (around 7%) and income from paid-for services (around 8%).

Trafigura Foundation began supporting ISWAN in 2017, originally to fund projects in India and the Philippines over three years, which extended the UK-based organisation’s international reach. Trafigura later committed to a new three-year investment, this time to support ISWAN to become more sustainable by increasing its earned income; it is now one of ISWAN’s core funding partners. Altogether, Trafigura Foundation has contributed more than £1 million to ISWAN’s activities.

ISWAN works with all stakeholders involved in the maritime industry, from seafarers’ unions to shipping companies; and like the Trafigura Foundation, it knows what it is to walk a tightrope between conflicting interests. Its independence, neutrality and ability to work with different parties is what has built its reputation, says CEO Simon Grainge.

ISWAN considered carefully whether it was right for it to accept a grant from the Trafigura Foundation, because of the foundation’s association with a big name in the shipping industry. “It was discussed, but it was felt that Trafigura Foundation’s motives were sound,” Grainge says, referring to the foundation’s focus on creating clean and safe supply chains. “We always felt unrestrained, never under pressure,” he adds.

Grainge would not hesitate to turn down money if he felt concerned about the real intentions of a funder – and in fact, he’s done this before. Prior to his role at ISWAN, Grainge worked with an organisation that supported homeless people in the UK. The organisation was often in confrontation with the local council – which, as it happened, was also an important funder. Grainge took the decision to turn down the council’s funding; losing 10% of the organisation’s budget, but keeping its impact integrity.

Dr Levente Fejes, corporate initiative research manager at EVPA, says Trafigura Foundation’s approach to impact integrity provides “a compelling argument” for partnership between grantees like ISWAN and corporate social investors: the foundation can demonstrate that its drivers are different to those of its related company.

“They do so through effective communication and evidence to back their claims. This exemplifies what successful mitigation actions directed towards the key stakeholder environment can achieve,” he says.

Picture: ISWAN distributes a hardship fund for seafarers, among other projects. Credit: Peter Cornelissen.

“This exemplifies what successful mitigation actions directed towards the key stakeholder environment can achieve”

Risk, reputation, results

The Trafigura Foundation was able to convince ISWAN of its motives. But it remains a challenge at times to demonstrate its independence to those investees, beneficiaries and citizens who might suspect that the foundation is being – as Faber puts it – “instrumentalised”.

Go back a couple of decades and negative views of Trafigura – as with other companies in the same industry sector – were “based on some reality”, says Faber. “When I say this, I mainly mean that that industry is carbon intensive, that it trades unpopular commodities such as coal and fossil fuels, works in countries where labour standards have not always been optimal in the past and where corruption can be rampant.”

However, although he says Trafigura has made much progress to become a responsible, accountable and sustainable firm, some negative perceptions persist. “Even though the company has tremendously improved its corporate practices over the past 20 years, the prejudice in public opinion is so strong that perceptions are simply hard to change – despite the fact that today’s corporate reality is incomparably better,” he explains.

So how is the Trafigura Foundation tackling this problem? Federica Poletti, senior communication and engagement manager, says that the best way to protect yourself from reputational risk “is the way in which you act”. But much of it also has to do with good communication. From the very beginning, the Trafigura Foundation has had its own website and communications channels, distinct from those of the company, which was crucial to build the foundation’s identity and explain what it does and why.

She says: “Our external communication is very much focused on being transparent and accountable for how we spend the money and the kind of organisations we support – but not going too far in showing off about what we're doing.”

The foundation lets its portfolio speak for itself, she adds: “The relationship that you create with grantees, NGOs around the world… is the best testimony that we are a foundation that [creates impact].” Being part of networks such as EVPA can also help to be recognised as a “valid actor” in philanthropy, she adds.

Faber adds: “I think that the reputational aspect, and this suspicion of greenwashing, is best prevented by showing the real results you are having in the field.”

There’s another important way in which Trafigura Foundation mitigates risks to its impact integrity, says Nicolas Malmendier, corporate initiative associate at EVPA: it hires employees with a civil society background, not a business one.

“While this decision is related to the skill set required to work for a philanthropic foundation it also provides clear advantages in the context of impact integrity, since it means they are inherently more focused on impact and lack a bias toward the company’s goals.”

Sometimes NGOs express concerns. But, says Faber, talking candidly to NGO trustees or executives is enough to alleviate these. “It’s about being open, being transparent, and explaining the modus operandi [of the foundation], so people feel reassured,” he says.

In very rare cases, potential partnerships have fallen through. But Faber insists the foundation will not hide its identity: it won’t change its name, because it is proud of where it stems from, nor diversify its source of funding – because its purpose is to make grants, not to fundraise.

Ultimately, it all boils down to one question, Faber says: who are you serving, the company or the beneficiaries? “That’s an intellectual exercise that I'm often doing, to make sure that we are doing the right thing, for the right reasons.”

Top picture: © Zay Yar Lin

Photos courtesy of the Trafigura Foundation,

Education for Employment Egypt, Planet Indonesia and ISWAN.

Education for Employment.

Education for Employment.